New Year's Resolutions

Synopsis : Often made, less often kept. How to improve your health, wealth and generosity … good habits for the season ahead, plus wildfires, bananas and XXXL beesuits. New Year’s Resolutions for beekeepers.

Introduction

Historically, the Babylonians used the start of their New Year as an opportunity to clear old debts, return a kindness or right a wrong. In 2000 BCE {{1}} these New Year’s resolutions were retrospective, they did something measurable to ‘correct’ a past event.

At some point in the last 4000 years resolutions evolved to become prospective … and acquired increasingly religious connotations. The Romans made promises to their god Janus after whom the month of January is named. The change from a lunar calendar also shifted New Year, from the Babylonian springtime to its current location, shortly after all the mince pies are finished and the tree has shed the last of its needles onto the carpet.

Lots of people – perhaps 40-50% of the population {{2}} make New Year’s resolutions and almost as many fail to keep them. In many cases this failure seems predestined; asked at New Year whether there’s an expectation that a resolution will be kept, only ~50% say they expect to achieve their goal.

In practice, that’s ambitious.

When asked one year later only 12% had managed to keep the resolution.

‘Close, but no cigar’ {{3}}.

These days the once predominantly religious resolutions have, for many, been replaced by ‘self promises’ that can be broadly categorised as health (e.g. lose weight, quit smoking, get healthier), finance/career (e.g. save money, reduce stress) or generosity (e.g. be helpful, donate to charity).

New Year’s Resolutions for beekeepers

And, in a blatantly-contrived way, some of these resolutions are also relevant to beekeeping.

Like everyone else, beekeepers are just as capable of not keeping their resolutions, despite the clear benefits of doing so.

So, in no particular order, let’s have a look at a few beekeeping resolutions tailored to our obsession but still recognisable as generic or popular New Year’s Resolutions.

Quit smoking

Most beekeepers are smokers, or at least use smokers.

In fact, the smoker is probably the most widely recognised tool of our trade. The smoke is used to calm the colony before inspections. It masks the alarm pheromones and so makes inspections a little easier. After smoking a colony and opening it up you will usually find a significant number of the bees gorging on open honey stores or nectar.

This probably accounts for the explanation that bees nesting in tree cavities have, over eons, evolved to respond to smoke from natural forest fires. This response includes gorging on stores so that the colony can abscond – a term used to describe the entire colony abandoning any brood and relocating – to set up home elsewhere.

This is almost certainly incorrect.

Firstly, bees exposed to wildfires do not abscond. Unfortunately they just get cooked, and almost certainly die from either heat or asphyxiation 🙁 . Or, if the nest survives the fire, they starve as there’s no forage in range. Secondly, if you assume it’s midseason and the queen is laying eggs like crazy, they probably cannot abscond as she will be too heavy to fly any distance.

What’s more, if you open a colony without using smoke there will still be bees gorging on honey stores … the disturbance alone is sufficient to make them do this.

Try it.

Mr Smoke-Too-Much

Just like the Monty Python character, you can smoke too much. If you do the bees get disorientated and distressed. On occasion I’ve had to smoke a colony heavily and it’s generally something to avoid (but they never abscond).

Many beekeepers probably rely on smoke rather more than they should. If you smoke a colony heavily at the hive entrance the bees will be driven up … to the exact region you want fewer bees when you manipulate the frames. A very gentle waft under the crownboard and the occasional very light puff to clear bees from the frame lugs should be sufficient.

There are alternatives to smoke. A plant mister with plain water works well for many colonies and is what I often use if I’m just inspecting nucs. There are also commercial smoke/smoker alternatives like Fabi-Spray or Apifuge.

One of the best ways to learn to use less smoke is to keep bees in a shed. If you are over-generous with the smoker you also end up getting ‘kippered’.

I leave the smoker outside the door and only retrieve it when initially opening a colony and very rarely during inspections.

Of course, the best way to need to use less smoke is to select for calm, stable bees when you are queen rearing.

So … perhaps don’t quit smoking, but as Bounder-of-Adventure suggested to Mr Smoke-Too-Much in Monty Python’s Flying Circus, ’better cut down a little’ {{4}}.

Reducing stress

The Oxford English Dictionary has at least 13 definitions for the term stress; although many automatically think of tension or anxiety, biologists also use the term to mean:

Disturbed physiological function occurring in an organism or cell in response to conditions, events, or factors that are deleterious or threatening.

Bees subjected to adverse conditions – like long-distance transport, temperature extremes or disease – show evidence of stress which can be quantified in changes to the levels of molecular markers such as pheromone receptors and immune responses. This ability to respond is important, but it can be at the expense of normal physiological activity; e.g. more fighting pathogens or keeping warm than following waggle dancing foragers or feeding developing larvae.

Whilst I’m not aware of any studies of inspection-induced colony stress {{5}} I’ve no doubt it occurs … and that it’s at least transiently detrimental. The pheromone levels and gradients in the hive are disrupted, the brood nest is flooded with light, the location of bees in the nest are disturbed.

So, if you assume that that it is detrimental, try and minimise it. Only open the hive if needed, be gentle, use minimal smoke, be quick and calm and controlled … and try not to drop any frames 😉 .

The stressed beekeeper

The greater the disturbance you cause to the colony, the more defensive the bees become. They start pinging off your veil, burrowing into creases in your beesuit, stinging your gloves.

You become aware of a feint but distinct whiff of ripe bananas … that’s the alarm pheromone produced from the Koschevnikov gland at the base of the sting.

Then things start going a bit Pete Tong.

Your stress levels rise, you use too much smoke, you try to work faster but consequently get clumsier, a bee gets inside your veil and you get even more stressed … and smoky … and clumsy … and stung.

If you are tense and anxious before even opening a hive the bees can probably sense it, and this may exacerbate things.

Beekeeping shouldn’t be like this.

To reduce your stress you need to:

- have confidence in your protective clothing – buy a good quality beesuit and wear additional layers underneath when needed

- wear gloves that enable good dexterity – thin nitriles rather than welding gauntlets

- take care to cover areas of weakness – cuffs, ankles etc. (the bees will find them)

- requeen defensive colonies as soon as practical from better quality stock

- learn to inspect the colony quickly and calmly by practising (don’t avoid conducting inspections)

- and, if you’re frightened of the sting reaction, take antihistamines in advance of apiary visits

Beekeeping is supposed to be an enthralling and relaxing pastime. If it’s a stressful battle – for you or the bees – then something is wrong.

Improved health

This is a huge topic and needs more than a few hundred words – here are three examples of good practice:

- many diseases are always present in the colony but only become a problem under certain conditions. Deformed wing virus (DWV) isn’t an issue until Varroa levels rise, chalkbrood often ‘disappears’ by mid-season as the colony strengthens. Weak colonies are often more susceptible to disease and/or more likely to show symptoms. It therefore makes sense to maintain strong colonies. Take account of environmental conditions; don’t split them too hard and feed if necessary. Wasps and robbing bees aren’t ‘diseases’ but strong colonies are also better able to defend themselves.

- ignore much of the nonsense you read in some surveys of colony losses. The biggest problem most beekeepers face is the toxic combination of DWV and Varroa. I would be amazed if these accounted for <75% of all annual colony losses. Isolation starvation? Nope … the winter bees died faster due to high levels of DWV and the little cluster froze to death. Monitor your Varroa levels a few times during the season and look out for overt DWV symptoms – much of either and you might need to intervene. Yes, there are other things to look out for, but mites and viruses are the biggest problem.

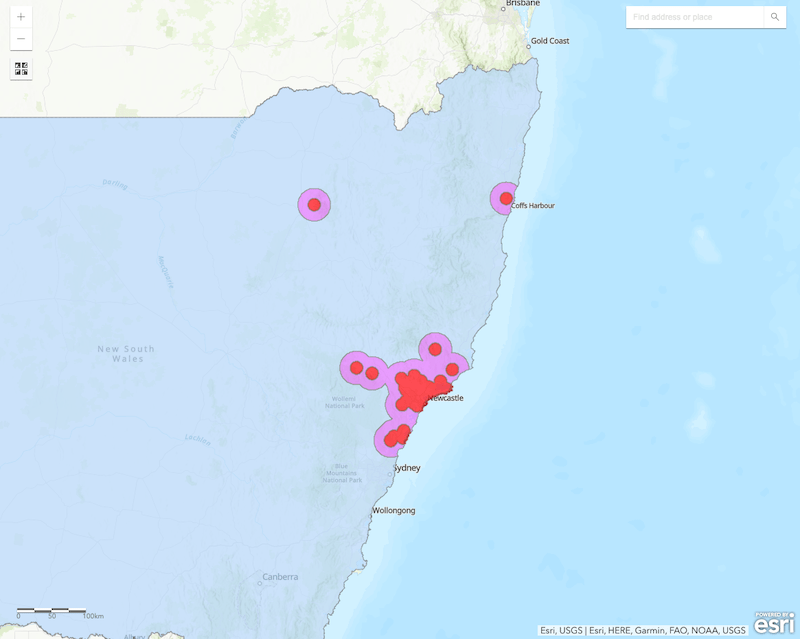

- beekeepers are responsible for spreading many pests and pathogens between hives and apiaries. If the global distribution of Varroa doesn’t convince you of this, then the map of Varroa presence in New South Wales should. Similar data exists for foulbroods, where the only reasonable explanation for the presence of the same strain miles apart is hive movements or contaminated equipment. Practise good biosecurity and remember, ‘when you move bees, you move disease’.

Save money

Some beekeepers already have a bit of a reputation in this area … ‘deep pockets, short arms’ as they say {{6}}. Even more beekeepers, whilst not actively mean, enjoy making savings wherever possible – if you want evidence of this just watch the stampeding hordes descend on the trade show sales at beekeeping conventions.

There are lots of ways to save money, at least after the initial expenditure on a hive (or two), beesuit, smoker etc.

Brood boxes and supers are probably best purchased as they are difficult/expensive to make without good tools, woodworking expertise and a source of high quality wood. Buy new cedar (even second quality) or poly boxes and they’ll last longer than you will. However, floors, roofs, crownboards and most of the things I consider as the horizontal components of the hive can be easily and inexpensively constructed.

Switching partly or totally to foundationless frames will save you a small fortune over the years.

Honey, honey

Of course, rather than reducing your outgoings, the other way to ‘save’ money is to raise your income.

Is your honey priced correctly? Beefarmers are talking about a glut after the good 2022 season, but I know plenty of places selling excellent local honey for £9-13 a jar (227 g or 340 g). The days when the milkman used to distribute and sell my honey for £4 a pound are long gone {{7}}.

Do your homework, use attractive jars, think about your labelling and remember that well produced local honey is a unique premium product and should be priced accordingly.

A final piece of advice on saving money. Omitting or skimping on Varroa treatments is false economy. I use Apivar and Api-Bioxal and spend less per hive per year than the cost of one 340 g jar of honey {{8}}. That’s a small price to pay {{9}} and is a cost I more than recoup from increased honey production or reduced overwinter losses.

Be more helpful

One of the best ways to learn is to teach.

If you’ve got a year or two of beekeeping experience why not volunteer to act as a mentor for beginners? By sharing the responsibility for an additional hive or two you will get more beekeeping experience than if you just manage your own. These additional colonies will make the distinction between ‘good’ bees and ‘poor’ bees much easier, particularly if they share a similar environment.

The inevitable questions from your mentee will challenge your understanding of the bees;

- Is this a queen cell or a play cup? What’s the difference between them anyway?

- Does this queen look inbred? Is there another explanation for a pepper-pot brood pattern?

- How do I cut out a queen cell overlaying a foundation wire?

As good as the training course was that I attended, and despite my attentiveness during my subsequent solo blunderings {{10}}, I’ve learnt much more from mentoring since I started.

Try it, you won’t regret it. You already know more than you think you know, and – if you’re anything like me – you’re only just realising how much else there is to learn.

Donate more to charity

I am aware of two charities that promote beekeeping in communities, supporting “sustainable beekeeping to combat poverty, build resilient livelihoods and benefit biodiversity” and who “mentor and train in local beekeeping best practices, business skills, and protecting the environment” {{11}} :

Both do really valuable work, primarily in Africa, but in other countries as well.

You can donate directly or purchase anti-tamper labels for jars that also help promote the work of the charity to the purchaser/consumers of your honey. Gift Aid donations if you can.

Lose weight

No, no, no … I don’t think so.

This one is the exception.

Other than during the self-flagellation exercise that is honey extraction, in particular shifting full supers from hives to the the store and then to the extractor, I don’t think there are any circumstances when beekeepers want less weight.

- I want my supers to be bloated with honey and I want them stacked head high.

- Colonies going into winter should be stuffed with stores and correspondingly heavy.

- I want the heaviest swarms possible to conveniently make their way to my bait hives. Bring it on, the more the merrier. They’ll get established faster and may even yield a good crop of honey (see 1, above).

There may be things I’m overlooking and my basic politeness means I have no intention of discussing anything to do with XXXL beesuits.

Does my bum look big in this?

Bargain basement

NHBS {{12}} currently have a special offer (£13.99 rather than £23.99) on Thomas Seeley’s The Lives of Bees. Although I’m not a fan of his Darwinian Beekeeping ideas, the book is an outstanding account of the biology of free-living honey bees. It is not a book about beekeeping but it explains loads of things about their behaviour which will help you understand why they’re doing what they’re doing.

{{1}}: Before Common Era (BCE; and CE for Common Era) are the secular versions of BC and AD. Well, almost secular, as they both use Dionysius’s estimate of the birth year of Jesus as a reference. Odd.

{{2}}: UK and US stats here from a variety of sources.

{{3}}: Particularly if you’d planned to give up smoking.

{{4}}: With apologies for those unfamiliar with Monty Python.

{{5}}: At least at the molecular level, there are some using hive monitors.

{{6}}: Interestingly, the idiom ’deep pockets’ means having lots of money, but coupled with ’short arms’ the wealth or otherwise of the Tyrannosaurus-limbed individual is irrelevant.

{{7}}: As has the milkman, and the pound … until the recent asinine suggestions to reintroduce imperial measures.

{{8}}: Premium local honey, not imported syrup @ 69 p.

{{9}}: Though the £150 outlay stings as I leave the store clutching those small foil packets.

{{10}}: Which continue to this day – blunderings that is, I’m getting less … er … what was I saying?

{{11}}: To use key phrases lifted directly from each their ‘About us’ pages.

{{12}}: No affiliation … I’m just on their mailing list and have bought from them before.

Join the discussion ...