Swarm control and elusive queens

Many beekeepers struggle to routinely find the queen, particularly in a very busy colony.

For 90% of the beekeeping season whether you find the queen or not is irrelevant … you can tell if she’s present because there are eggs in the colony (so she must have laid them in the last 3 days) and, often, because the colony is well-tempered.

That should be sufficient.

Whenever I do routine inspections I like to see the queen, but I don’t look for her. If the colony:

- is calm and well-behaved

- is bringing pollen in

- contains no sealed queen cells, and

- contains eggs

then I’m 99% certain there is a queen present and everything is OK {{1}}.

Individually, each of those observations isn’t a certain way of determining the queen status of the colony, but together they’re pretty-much a nailed-on certainty.

Not finding the queen

Notwithstanding the surety these four signs provide about the presence of the queen, they still don’t help you (or me ? ) find her.

And, for a few colony manipulations, it’s really helpful to find the queen. Indeed, for some it is essential.

I’m not going to discuss ways to help find the queen as I’ve written about it before and refer you there for starters.

The two obvious times it helps to know exactly where the queen are:

- when you are removing frames, brood and bees from the colony – for example, when making up nucleus colonies

- during swarm control

Frankly, you probably shouldn’t be doing the first of these if you don’t know where the queen is. There’s a real risk of leaving the parental colony queenless, which is probably not your intention.

Swarm control

The post today is going to deal with the second situation. How do you conduct swarm control when you don’t have a Scooby {{2}} where the queen is in the colony?

Swarm control is the term used to describe the colony manipulations that a beekeeper conducts to prevent the loss of a swarm. It is usually started after attempts at swarm prevention (e.g. supering early to provide more space) have clearly not worked.

You can tell the swarm prevention has not worked because the colony has started to produce queen cells … don’t panic.

This seemed like a logical post for this time of the season … and for another Covid-blighted spring. Beginners who started last year, or who will be getting their first bees this year, might well have to conduct swarm control without the benefit of a mentor.

And it’s beginners who are most likely to be unable to find the queen in an overflowing colony. These of course are the colonies that are most likely to swarm and – because of their ability to collect lots of honey – the very colonies you want not to swarm ?

Swarm control when you can find the queen

All of the methods of swarm control I’ve previously discussed here have involved hive manipulations that require the location of the queen to be known:

- The Pagden artificial swarm – the queen is left in the original location and is joined by all the flying bees. The brood and hive bees end up rearing a new queen.

- The vertical split – the same as the Pagden artificial swarm, except conducted vertically rather than horizontally. Uses less equipment and more muscle.

- The nucleus method – a nuc colony is established with the queen, some bees and brood. The parental colony is left to rear a new queen. Very reliable in my experience.

If you’re the type of beekeeper who can routinely find the queen, relatively quickly, however crowded or bad tempered the colony is, however short of time …

… in a downpour.

Congratulations. Apply here. No need to read any further ?

But, for the rest of us …

Queens and bees

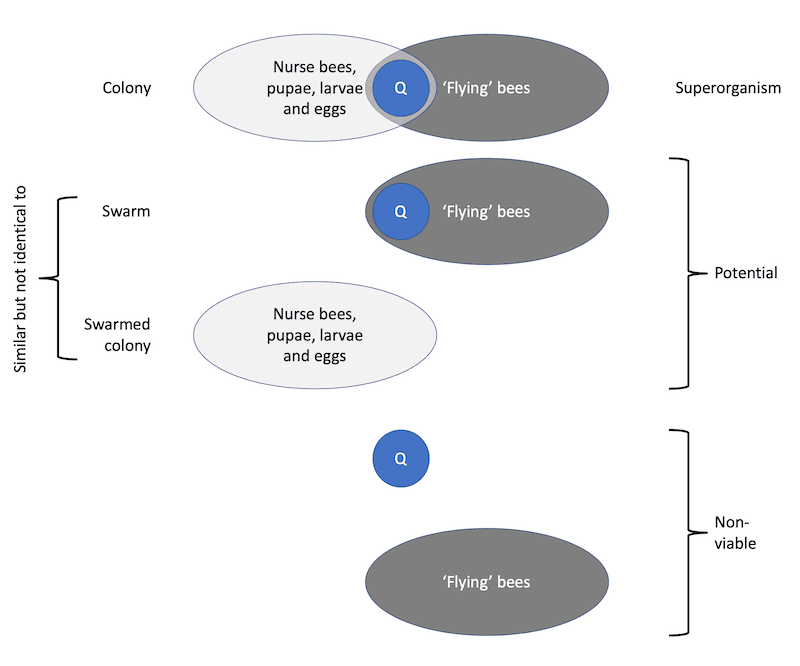

If you think about the contents of a colony it can be divided into three components:

- Queen

- Brood in all stages (eggs, larvae, pupae; abbreviated to BIAS) and the nurse or ‘hive’ bees

- Flying bees – the foraging workforce

Of these, only one is a ‘viable’ entity on its own.

The queen needs bees to feed her, build comb and rear the larvae that hatch from the eggs she lays. The foragers need a queen to lay eggs. Neither alone is viable, by which I mean ‘has the ability to develop into a full colony’.

In contrast, the combination of nurse bees and brood, in particular the eggs and very young larvae, does have the potential to create a complete colony.

I’ve discussed this concept before under the title Superorganism potential.

Although neither the queen or flying bees alone have any long-term potential to create a new colony, together they can.

Both the Pagden and vertical split exploit this potential by separating the queen and flying bees from ‘all the rest’. It’s similar, but not identical to what happens when a colony swarms {{3}}.

Loads of bees … and there’s a queen in there somewhere!

The method described below is a slight modification of the Pagden artificial swarm.

It exploits the fact that the flying bees return to their original location with unerring accuracy {{4}}.

It couples this with the ‘Get out of jail free’ ability of bees to rear a new queen from eggs or very young larvae if they are queenless.

Together they make swarm control straightforward when you can’t find or don’t know where the queen is.

Or when you don’t have the time or patience or enthusiasm to find her ?

So, let’s move from generalities to specifics …

During a routine inspection of a colony in late May {{5}} you find unsealed queen cells. The colony is strong and you’ve not seen the queen for weeks. Or ever. She’s not marked or clipped. There are eggs, larvae and sealed brood in abundance.

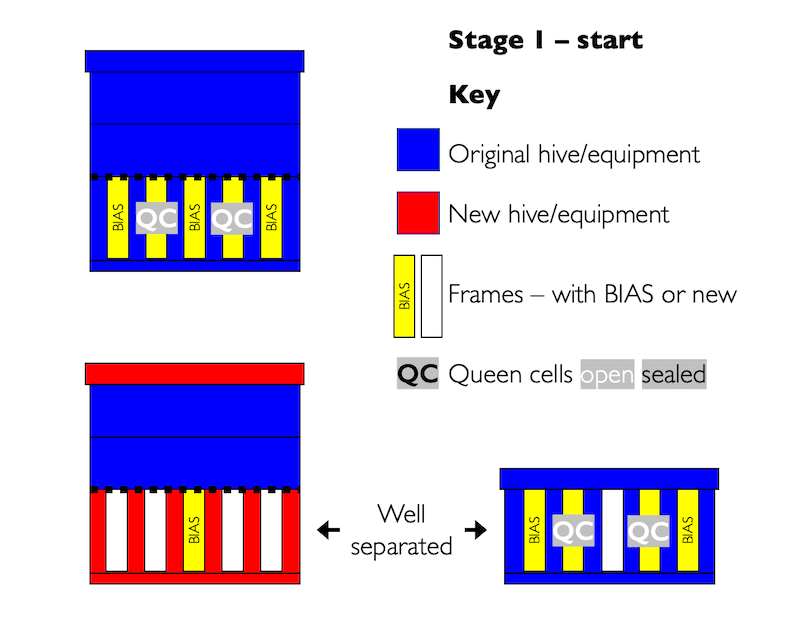

Stage 1 – preparation

- Check the colony again for any sealed queen cells. If you find any you should assume that the colony has probably already swarmed {{6}}. If there are no sealed queen cells continue …

- Beg, borrow or steal a new floor, brood box, crownboard and roof. While you’re at it, scrounge or build 11 new frames. Of course, I expect all readers of this site are better prepared than

methat. You will have spares close to hand – in the apiary shed, or the back of the beemobile, or you can quickly disassemble a nearby bait hive. Congratulations … I hope you’re feeling very smug ? - Move the soon-to-swarm colony (which I’ll term the old colony in the old hive from now on) away from its original location. Most advice suggests more than a metre. I prefer to move the old hive further away (e.g. to the other side of the apiary). You want to ensure that bees flying from the old hive relocate to the new hive. If you’re short of space at all it helps to rotate the old hive entrance to face in a different direction.

- Place the new floor and new brood box in the original location. Make sure the entrance faces the same way as it did when the old hive was in the original location.

You’ll notice that returning foragers will start to enter the new hive almost as soon as you place the floor and brood box in place.

Stage 1 – provision the new hive with eggs and larvae

- Remove the roof, crownboard, supers and queen excluder from the old hive and place them gently aside.

- Transfer one frame containing eggs and young larvae from the old hive to the new hive.

- It is imperative that the selected frame has no queen cells on it. Carefully inspect the frame for queen cells. If you find any, knock them off using your hive tool or fingers. The ability to judge which of the two hives contains the queen at the next inspection is dependent upon there being no queen cells at this stage.

- Place the selected frame in the middle of the new hive.

- Fill the remainder of the new hive with new frames.

- Add the queen excluder to the new hive {{7}}.

- Add the supers to the new hive. Close the new hive by adding a crownboard and roof. See the note below about feeding this colony.

- Add a new frame to the gap now present in the old hive {{8}}. Replace the crownboard and roof.

- Go and make a cup of tea … all done for today.

I’ve assumed that the colony you are manipulating has supers present. If it did not, and particularly if there’s no nectar flow, you will need to feed the colony in the new hive. This ensures that the bees can build comb … which they’ll need to do if the queen is present.

You now leave the colonies for 7 days and then check them again to determine which contained the queen …

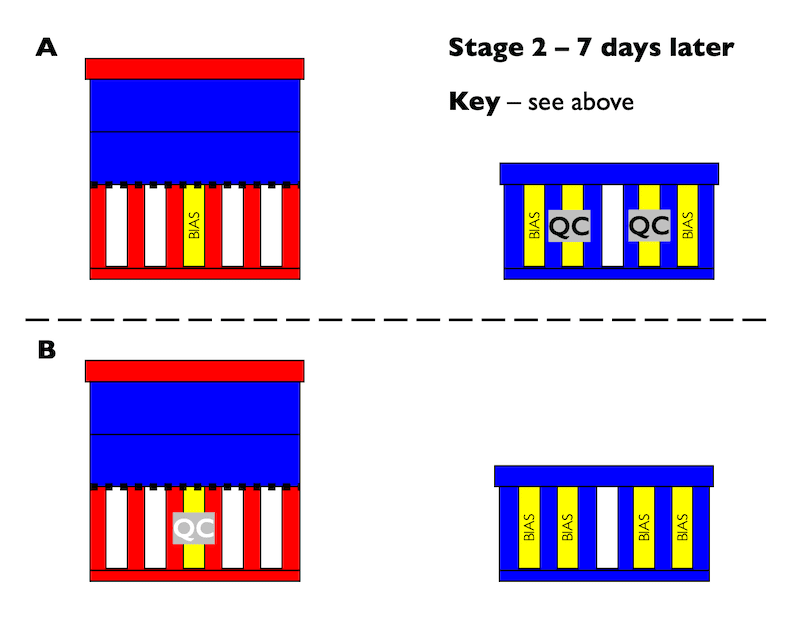

Stage 2 – 7 days later – the new hive

Inspect the new hive and look for queen cells on the frame you transferred from the old hive in stage 1(ii) (above). This hive will be much busier now as all of the flying bees from the old hive will have relocated to it

The new hive contains no queen cells

If there are no queen cells on the brood frame you introduced it is almost certain that the queen is in the new hive (see upper panel A in the diagram below). Look carefully on the frames of adjacent drawn comb for the presence of eggs. If so, you can be certain that the queen is in the new hive. Close the hive and let them get on with things.

The new hive does contain queen cells

If there are queen cells on the frame you transferred from the old hive then the queen is almost certainly not in the new hive (see lower panel B in the diagram below).

Because they are queenless and you provided them with a frame containing eggs and very young larvae they have started to produce a new queen … or queens.

You want to make sure they only produce one new queen.

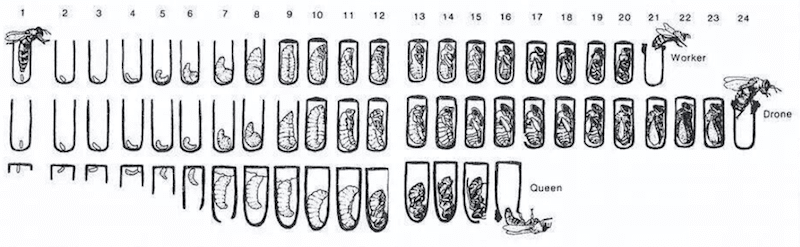

There will be no more eggs or larvae young enough to start more queen cells. Many of the queen cells will be capped.

Ideally, select an unsealed queen cell that contains a big fat larva sitting in a deep bed of Royal jelly (a ‘charged’ cell). Mark the top of the frame with a pin (if you’re organised) or pen (if you’re less organised) or a hive tool (if you’re me ? ). Knock off all the capped cells, just leaving the one you have marked.

Be gentle with this frame. Don’t shake it, don’t drop it etc.

Close the hive up and let the queen emerge and mate and start laying. This will take at least 17 days or so, and often longer.

Stage 2 – 7 days later – the old hive

Inspect the old hive and look for queen cells. This hive will be much less busy as most of the flying bees will have been ‘bled off’ returning to their original location (and boosting the population in the new hive).

The old hive contains no queen cells

With a much reduced population of workers – and if the queen is present – the bees will no longer need the queen cells, so will almost certainly have torn them down and destroyed them (see lower panel B in the diagram above).

If you carefully look through this hive you should find eggs and very young larvae present. These ‘prove’ that there is a queen present, even if you still cannot find her. Where else could the eggs have come from?

Close the hive up and let them get on with things.

The old hive does contain queen cells

Despite the reduced worker population, if this hive does not contain the queen the bees will be busy rearing a replacement … or three.

There will be no more eggs or larvae young enough to start more queen cells. Many of the queen cells will be capped.

Ideally, select an unsealed queen cell. Mark the top of the frame with a pin {{9}}. Knock off all the capped cells, just leaving the one you have marked.

The goal is the leave one charged queen cell only.

If all the cells are capped don’t worry. The bees are very unlikely to have chosen a ‘dud’. Choose a nice looking cell somewhere near the centre of the brood nest and destroy the others.

Make a note in your diary/notebook and expect to wait 17-21 days until this queen is out and mated and laying (or possibly a bit longer). Other than perhaps checking the new queen has emerged there’s no need to disturb the colony in the meantime (and lots to be lost if you do interfere and disturb the virgin queen).

It’s as simple as that … what could possibly go wrong?

I’ve very rarely had to implement swarm control when I can’t find the queen. Usually I’ll just look a bit harder and find her eventually.

However, there are times when knowing what you need to do if you really cannot find her – because the hive is full of uncapped swarm cells and it’s raining hard, or the bees are going postal and you want to be anywhere but in this apiary next to the open hive – is very useful.

Are there any embellishments that might be worth considering?

If the old hive has very little comb with eggs and young larvae you need to ensure that both the old and the new hives have sufficient to draw new queen cells. This is rarely a problem, but be aware that this method only works if both old and new hives have the resources to rear a new queen should they need to.

On the contrary, if there’s ample eggs/larvae you could transfer a couple of frames to the new hive … remembering that there’s also then an increased chance you will also be transferring the elusive queen.

If the old hive is left with ample eggs and larvae you can safely knock back all the queen cells during stage 1. They will only then produce new cells if the queen is not present. This makes deciphering what’s going on at 7 days that much easier.

When I say 7 days, I mean 7 days … not 9, or when it stops raining or when you’ve got some spare time in the future ?

A queen in a cell capped on the day you complete stage 1 will emerge 9 days later. On the off chance that the bees are queenright but do not tear the unwanted cells down you want to avoid this happening.

Finally, if there’s a dearth of nectar and no filled/partially filled supers on the colonies, you may need to feed them to avoid starvation.

Keep a close eye on them, but don’t interfere unless you have to.

{{1}}: As often as not, if you go through the colony calmly and using little smoke you’ll see her anyway.

{{2}}: Scooby is an abbreviation of Scooby Doo, which is pseudo-Cockney rhyming slang for ‘clue’. Appropriately for a blog based in Scotland, the first recorded use was in the Glasgow Herald in 1993 “Your lawyer telling youse that he husnae a scooby and youse can jist take a wee tirravie tae yersel” (tirravie means fit of rage, the rest you can probably work out!).

{{3}}: Not identical … because the age distribution of bees in a swarm is strongly biased towards the younger bees in the hive.

{{4}}: Actually, it’s not unerring. Drifting of bees between colonies occurs at a significant rate as far as disease management is concerned. But, as far as we’re concerned today it’s unerring.

{{5}}: Or whenever.

{{6}}: If the colony has swarmed there is no point in continuing … you instead need to ensure that only one new queen emerges.

{{7}}: It’s worth shaking all the bees off the queen excluder into either the old or new hives. If you don’t there’s a remote risk the queen might end up above the queen excluder … another case of don’t do as I do, do as I say.

{{8}}: See the note below about knocking back queen cells in the old hive.

{{9}}: Having learnt the hard way that marks made with a hive tool are often difficult to subsequently find.

Join the discussion ...