Shook swarms and miticides

Synopsis : Combining a shook swarm with miticide treatment removes most mites in the colony and dramatically reduces DWV levels. The application of this strategy for practical beekeeping is discussed.

Introduction

Why does Varroa have such a devastating impact on colony health?

Feeding on haemolymph – or the abdominal fat body – by Varroa is probably detrimental. Furthermore, during feeding the mite induces immunosuppressive responses which make the bee both more susceptible to bacterial infections and compromises its nutritional status (Aronstein et al., 2012 {{1}} ).

But if that wasn’t enough, the real damage is caused by transmission of viruses – in particular deformed wing virus (DWV) – from the mite to the developing pupa (and adult worker, as mites probably also feed on newly eclosed workers during the misnamed phoretic stage of the life cycle).

In the absence of Varroa, DWV is seemingly inconsequential for honey bees. Varroa-free colonies – including mine on the remote west coast of Scotland – carry DWV, but virus levels are very low and there is never any overt disease.

But Varroa infested colonies, particularly at this time of the season, often have very high levels of DWV.

Individual pupae parasitised by Varroa can develop stratospherically high DWV levels – reaching over a million times higher levels than seen in unparasitised bees (which can be similar to those recorded in Varroa-free bees). In the mite-exposed pupae the virus levels can kill the developing bees, or result in the characteristic symptoms (primarily deformed wings but also stunted abdomens and discolouration) that give the virus its name.

But bees not directly exposed to Varroa also have higher DWV levels in mite-infested colonies, particularly as the season progresses. Presumably this is due to horizontal transmission of the virus during larval feeding or trophallaxis.

What happens to these elevated virus levels after the removal of Varroa using a miticide such as Apivar?

Who cares? … I mean, Why could that matter?

The clue is in the section above.

Here it is again:

But bees not directly exposed to Varroa also have higher DWV levels [ … snip … ] presumably this is due to horizontal transmission of the virus during larval feeding or trophallaxis.

If you remove mites the virus levels in the treated adult bees are often surprisingly high {{2}}. That makes sense because the miticide is only removing the vector for the virus … the bees with high levels of virus infection are unaffected.

If, during larval feeding or trophallaxis, these elevated levels of DWV result in yet more bees acquiring high DWV levels then the health of the colony will remain compromised.

The real reason that DWV is a problem for honey bees is that high levels of the virus result in the reduced longevity of bees. This isn’t an issue for the short-lived summer foragers {{3}}. However, reducing the longevity of the winter bees – the so-called diutinus bees – can be fatal for the colony. These are the bees that support the queen in winter, thermoregulating the hive and that rear the first brood of the following season.

Their importance to successful overwintering cannot be overemphasised.

So, the question remains. What happens to the virus levels in the hive after the removal of Varroa?

Of course, the reason I’m posing this question is that we now know … 😉 .

Two easy-to-understand potential outcomes

It seemed to us that there were at least two likely outcomes.

- The virus levels in the hive drop very quickly after mite removal (red dashed line, below) and return to some sort of basal level. How quickly and to what basal level? We didn’t know.

- Virus levels remain elevated for a long period after Varroa is removed (red solid line, below). How long and to what elevated level? Yes – you guessed it – we didn’t know 😉 .

Of course, biology isn’t binary. There are any number of alternative outcomes … it’s just that those two seemed the most likely.

What’s more, they’re the easiest to understand … and to explain.

Why might virus levels remain high if Varroa are removed?

Surely the short lifespan of adult bees means these would soon be lost from the colony … particularly if they have reduced longevity?

Yes, but …

We published a paper a couple of years ago that clearly demonstrated that honey bee larvae fed high levels of DWV became infected with the fed virus. The latter, which we could distinguish from any DWV already present in the larvae, replicated to similar high levels seen in a mite-infested hive (Gusachenko et al., 2020).

This observation perhaps suggested that the second scenario outlined above could occur. All the mites are slaughtered, but the remaining bees with high levels of DWV feed developing brood which consequently also go on to develop high levels of DWV.

Although it’s always good to remove mites this would not be the best outcome for the colony.

Virus quantification

Before I explain how we tested which, if any, of these two possibilities is correct I need to say a few things about virus ‘levels’.

For a variety of reasons I don’t have time, space or energy to explain, we don’t actually count viruses, instead we count copies of the virus’s genetic material (the genome).

The virus genome is made of ribonucleic acid (RNA) and we can therefore use fantastically expensive sensitive and accurate diagnostic methods to measure how many copies are present in a particular sample – for example, in a worker bee, or a developing pupa.

Still with me?

Good.

To complicate things a little, we can’t meaningfully express the number of virus genomes present as an absolute number (like one million, or 2,478) because bees are different sizes; larvae are tiny, pupae are bigger, drones are larger still.

In addition, different workers are different sizes, larvae grow etc.

Therefore we express it as genomes per unit of total RNA extracted from the sample. That’s a bit of a mouthful, so we abbreviate it to GE / μg {{4}}.

Phew!

And finally, to put some numbers on the low and high levels of DWV I discussed earlier, a bee from a Varroa-free colony contains ~1,000 – 10,000 GE / μg (103 – 104) of DWV whereas a pupa parasitised by Varroa regularly has 10,000,000,000 to 1,000,000,000,000 GE / μg (1010 – 1012).

That’s a lot of virus 🙁 .

The experiments

Experiments plural because we did these studies in both 2018 and 2019. ‘We’ are Luke (a then PhD student and now post-doctoral fellow in my laboratory, and the first author on the paper) together with our friends and collaborators, Craig, Ewan and Alan (in Aberdeen) and Giles (in Newcastle). The work was published a few days ago in the journal Viruses and is ‘open access’ (Woodford et al., 2022). This means that anyone feeling particularly masochistic or suffering from sleep deprivation can read all the gruesome details at their leisure.

The paper covers more than just the one experiment I’m going to discuss here. We also looked at how the virus population changes when mite-free bees become infested with Varroa.

I’ll save that for another post {{5}} … it’s a good story in its own right.

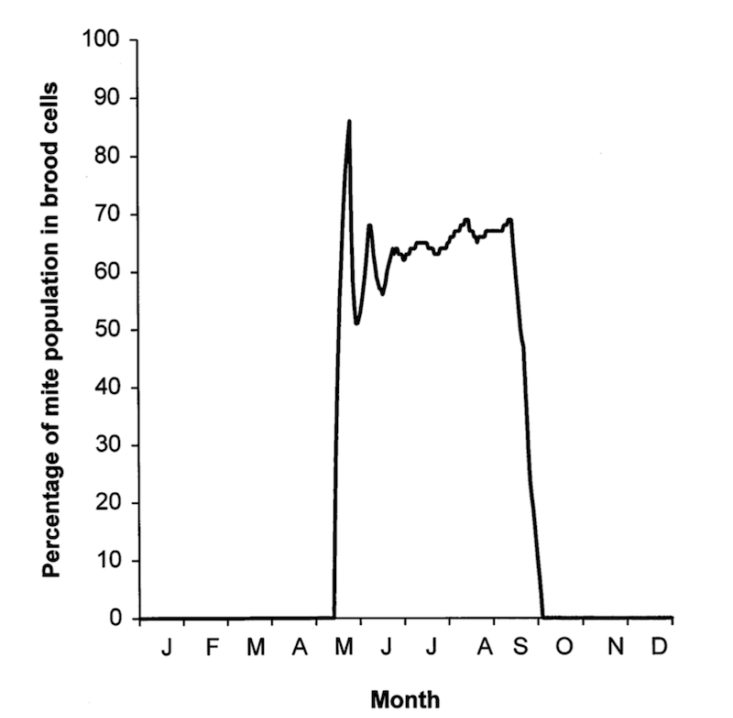

Most mites are in capped cells

It’s been known for at least three decades that the majority of the Varroa population in a brood rearing colony are within capped cells, feasting on developing pupae.

Nom, nom, nom!

Precisely what percentage of the population is the majority varies a bit {{6}}, but a figure of 90% is often quoted as typical for midseason.

We reasoned that the best way to quickly remove all {{7}} the Varroa in a colony was to combine treatment of the phoretic mites with removal of all the brood … where the majority of the mites are lurking.

And to remove the brood (and associated mites) we conducted a shook swarm.

The shook swarm

Many beekeepers will be familiar with the technique called a shook swarm.

Shook swarm setup. Note Apivar strips in the open hive. Returning foragers already clustering at the entrance

This involves shaking all the adult bees into a new hive with frames containing fresh foundation. All the old frames and brood from the original hive are discarded.

We modified this by including Apivar strips in the hive into which we shook the adult bees.

Shook swarmed colony strapped up for transport … we wait for all the bees to enter the hive before moving it

The ‘shook swarm and miticide’ experiment – which we conducted in May – therefore involved the following steps (we used three strong double brood hives per season, each containing similar amounts of bees and brood):

- We quantified DWV in emerging brood in hives in which no Varroa management was conducted.

- The queen was removed, caged and kept safe for a few hours.

- All adult bees were shaken into a new brood box containing 11 frames of fresh foundation and two strips of Apivar {{8}}.

- The shook swarms were relocated to a quarantine apiary.

- The queen was returned to the shook swarmed colonies and they were fed ad libitum with syrup to encourage them to draw fresh comb.

- Mite drop was recorded at 5 day intervals, increasing to longer intervals, until October when brood rearing ceased.

- DWV levels were quantified on a monthly basis from June to October.

As you can see, a very simple experiment.

The results

The mite levels in the ‘donor’ hives were much higher in 2019 than 2018. It’s not unusual to see this type of year to year variation in mite levels. In this instance the mean temperature in February and March 2018 had been several degrees colder than 2019 (remember the Beast from the East?).

This almost certainly reduced early season brood rearing and so delayed mite replication. Brood rearing was strong by late Spring, but the mite levels in 2018 had yet to catch up.

The results of the experiment in both years were essentially the same. However, for clarity I’ll just present the 2019 data as the mite infestation numbers were so dramatic.

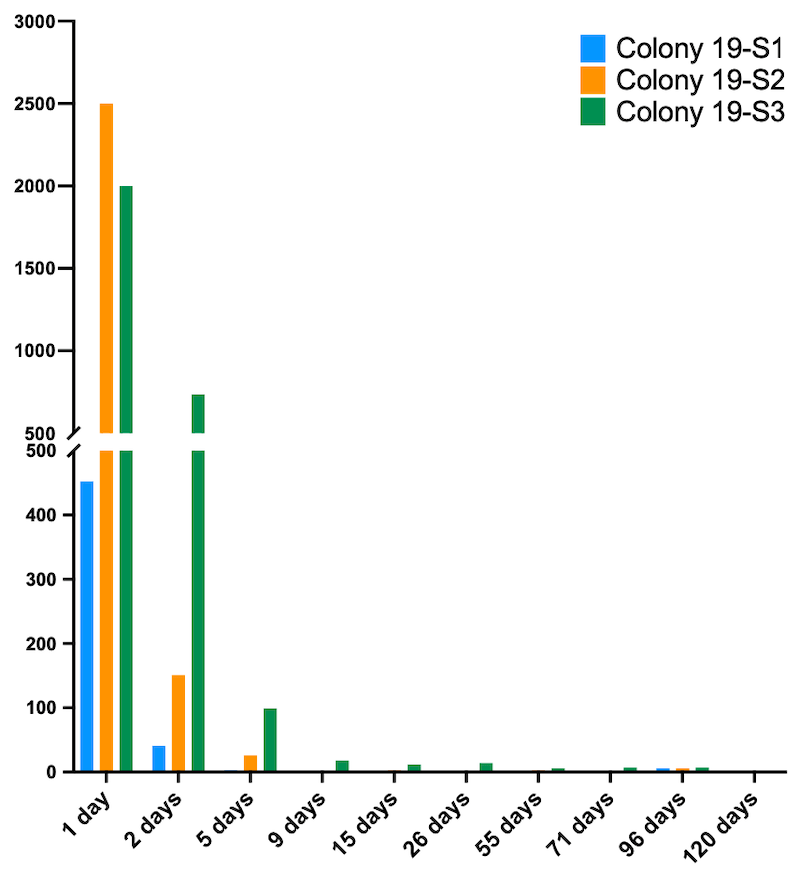

Mite drop after conducting the shook swarm

The cumulative mite drop from Apivar-treated shook swarms ranged from ~500 to ~3000 in the first 5 days. After that the daily mite drop remained at extremely low levels until recording stopped in October.

If you assume that only 10% of mites were phoretic at the time we conducted the shook swarm, this means that the total number of mites in some of these colonies was about 30,000. Even the colony with the lowest mite drop may have been hiding an additional 4,500 mites in capped cells.

Remember … the National Bee Unit guidance states that if mite levels exceed 1,000 then treatment is strongly recommended ’to avoid Varroa causing significant adverse effects to the colony’.

I think this part of the study shows just how effective Apivar is. After the first 5 days of treatment the cumulative drop – the Apivar strips still were left in place for 8 weeks – was extremely low for each fortnightly sampling period.

Of course – other than the very high numbers – none of this was particularly surprising. We know Apivar kills Varroa.

Perhaps you’re thinking ”My hives drop more Varroa during the autumn treatment, and for longer.”

When you treat a colony with brood present the mite drop is high in the first few days, but then often remains significant over the next 2-3 weeks while the mite-infested brood emerges.

In our case, all the mites were on adult bees. By killing these mites in the first few days before there was new sealed brood in the colony we ensured the majority of the new brood did not become infested.

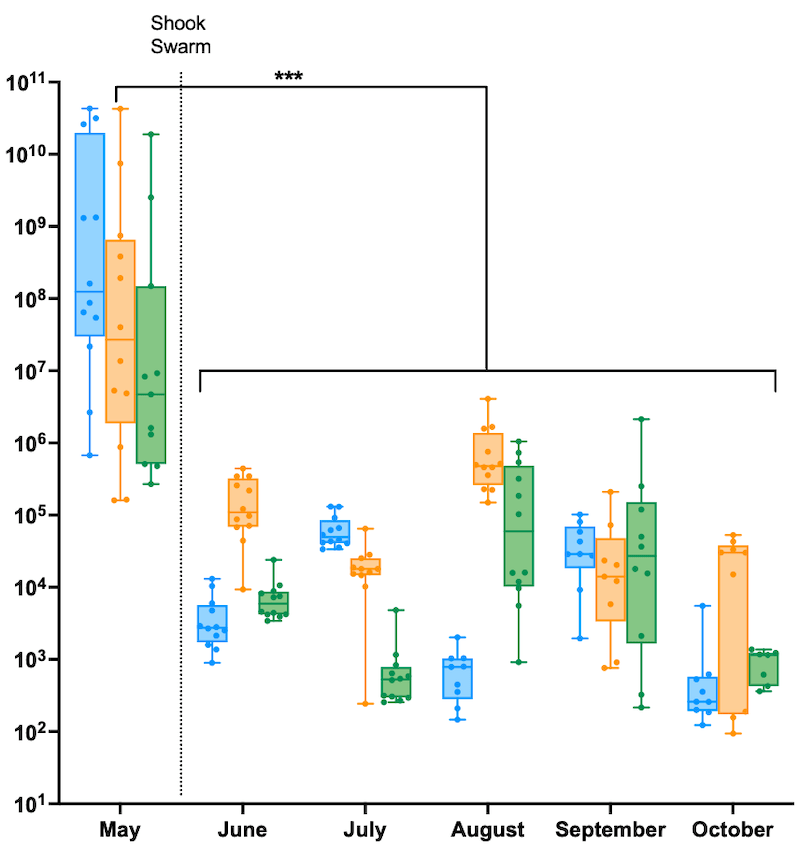

Virus levels before and after the shook swarm

In each colony we sampled a dozen emerging workers, once before the shook swarm and then on a monthly basis until brood rearing stopped. By testing emerging brood we could be certain they had been reared in the test colony, rather than drifting in from elsewhere.

Before the shook swarm virus levels ranged from 105 to 1010 per worker, with an average of around 5 x 107 GE / μg. For those of you unfamiliar with scientific notation that is 50 million virus genomes.

Virus quantification in individual workers from colonies before and after the shook swarm and Apivar treatment

Strikingly, from the June sample onwards, virus levels dropped to an average of about 104 GE / μg (10,000 virus genomes, a 5,000-fold reduction). This average obscured a range of individual levels, from about 102 to 106.

These reductions are statistically significant … always reassuring 😉 .

The 2018 data showed a similar marked reduction in virus levels. The pre-treatment levels were marginally lower (remember, it was a ’low Varroa’ season), but the levels dropped to an average of only 1,000 GE / μg, a slightly higher fold-reduction and again highly statistically significant.

If you remove the majority of the Varroa the virus levels drop very fast to levels seen in mite-free colonies, or colonies with very low mite counts.

Tough love?

Some beekeepers consider that a shook swarm is tough on the colony.

I’m not sure I agree.

How and when the shook swarm is done matters a lot.

It can be tough, but it shouldn’t be.

The bees need to draw new comb. For this they need ample feeding, lots of bees and warm weather. By conducting shook swarms on strong colonies in late May and giving them a few gallons of syrup we achieved all this.

Doing a shook swarm on a weak colony, too early (or late) in the season or omitting feeding is a recipe for disaster. The colony will struggle to draw comb, its brood rearing will be limited and it will be playing ’catch up’ for the remainder of the year.

Our shook swarmed colonies were booming by late July and entered the winter very strong. All overwintered successfully.

I’d argue that a shook swarm is a lot less tough on a colony than the disease burden caused by thousands of mites … 🙁 .

Why Apivar?

It’s worth emphasising that this was a scientific experiment to investigate the consequences for the virus population of removing almost all of the Varroa.

It was not designed as an example of how a beekeeper would necessarily choose to manage a honey production colony.

Our choice of Apivar was considered and deliberate. Application is straightforward, toxicity – at the levels we used – is undetectable and, critically for these studies, it remains active for weeks.

Of course, Apivar cannot be used when there are honey supers on the hive {{9}}. Any supers added for the summer nectar flow were not extracted.

Additionally, feeding gallons of syrup when there are honey supers present is also not recommended 😉 .

What else could we have used?

The two obvious choices were MAQS or oxalic acid. Both are effective against phoretic mites, though perhaps less so than Apivar. However, both are only active for a short period in the hive; the treatment period for MAQS is 7 days and the activity of oxalic acid – trickled or vaporised – is probably less than a week.

Neither could be relied upon to slaughter the maximum number of mites, a necessity to produce an understandable result {{10}}. We were additionally concerned about problems with queens or absconding had we used MAQS (both of which would have invalidated the study), and we were keen to avoid the need for repeat treatments with oxalic acid (not least because this is not an approved application method).

With thousands of mites we wanted to ensure that the majority were killed quickly … and, as important, that any that survived the first few days of miticide treatment were also more than likely to be killed later {{11}}.

Application to practical beekeeping

The main aim of this experiment was to investigate the levels of DWV in the colony after the majority of Varroa are removed. However, we were also mindful that the method may be useful for a beekeeper who discovers his/her colony has damagingly high mite levels mid-season, or for someone who inherits abandoned hives with high mite loads.

In these scenarios, assuming there are sufficient bees, some nice warm weather and lashings of syrup available, the combination of a shook swarm and simultaneous miticide application is probably the fastest way to restore colony health.

I am not suggesting that beekeepers routinely conduct a shook swarm and miticide application mid-season. It might not be tough on the colony, but that doesn’t mean it’s not very disruptive. If it’s not needed (because mite levels are well controlled, for example) then it’s a waste of brood … and syrup.

However, there are times when I could imagine it might be useful.

If your primary crop is heather honey you’ll know that the hives sometimes don’t come back from the hills until late-September. That’s late to be applying miticides to protect the winter bees. In an area with an extended June gap (which often starts in May) it might be possible to effectively rid the hives of Varroa in June and have a strong colony to take to the moors in early August.

This is probably a better approach than using a half dose of Apivar in June (as some do) which probably doesn’t kill all the mites anyway, risks contributing to amitraz resistance in the mite population and may result in Apivar strips being left in the hive during the heather flow {{12}}.

Conclusions

Miticides kill mites … big deal.

However, it’s the viruses – in particular deformed wing virus – that kill colonies.

We have now shown that removing the majority of the mites from a colony (including those associated with sealed brood) results in the levels of DWV in the hive dropping very quickly.

The speed with which this happens – four weeks or less – is probably accounted for by the lifespan of the adult bees in the colony following the shook swarm.

This suggests that high levels of virus are not horizontally transmitted or (and this is subtly different) that horizontal transmission, through feeding, of large amounts of virus does not result in elevated levels of virus replication in the recipient bee (larva or adult).

All sorts of questions remain. Would oxalic acid be a suitable replacement for Apivar? How much virus is transferred from a worker to a larva during brood rearing, or between workers during trophallaxis? Is this below a threshold for efficient infection? Do virus levels drop as dramatically when treating a broodless colony (e.g. after caging the queen for three weeks)?

In the meantime just remember that ”the only good mite is a dead mite” … and, if you kill the mites, you also quickly reduce virus levels to a level at which they do not damage the colony.

And a straightforward way to achieve that is to combine a shook swarm with an effective miticide.

Result!

References

Aronstein, Katherine A., Eduardo Saldivar, Rodrigo Vega, Stephanie Westmiller, and Angela E. Douglas. ‘How Varroa Parasitism Affects the Immunological and Nutritional Status of the Honey Bee, Apis Mellifera’. Insects 3, no. 3 (27 June 2012): 601–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects3030601.

Gusachenko, Olesya N., Luke Woodford, Katharin Balbirnie-Cumming, Ewan M. Campbell, Craig R. Christie, Alan S. Bowman, and David J. Evans. ‘Green Bees: Reverse Genetic Analysis of Deformed Wing Virus Transmission, Replication, and Tropism’. Viruses 12, no. 5 (May 2020): 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12050532.

Woodford, Luke, Craig R. Christie, Ewan M. Campbell, Giles E. Budge, Alan S. Bowman, and David J. Evans. ‘Quantitative and Qualitative Changes in the Deformed Wing Virus Population in Honey Bees Associated with the Introduction or Removal of Varroa Destructor’. Viruses 14, no. 8 (August 2022): 1597. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14081597.

{{1}}: Remember … posts now contain a proper reference list at the end. Fill yer boots!

{{2}}: Perhaps 10,000 to 100,000 times higher than mite-free bees.

{{3}}: Actually, formally we don’t know this. As I showed in a recent post there is a class of experienced elite foragers that do the majority of the nectar and pollen gathering for the colony. If these were lost it may be detrimental to the nutrition of the colony.

{{4}}: genome equivalents per microgram

{{5}}: You can have too much of a good thing.

{{6}}: For reasons that I’ll maybe explain in another post as it is important in quantifying mite levels from the mite drop.

{{7}}: Formally, almost all … for reasons I’ll definitely cover in another post. Generally miticide treatment reduces (massively) but does not eliminate mites from the colony.

{{8}}: The ‘discarded’ brood frames were distributed to other hives in the ‘mite-infested’ apiary.

{{9}}: Or rather, it can be, but the honey is tainted and cannot be used for human consumption. If I have supers like this I store them safely and put them underneath a strong hive in the autumn to supplement the winter feeding.

{{10}}: I’m assuming you’ve not read the paper in full or you might argue with this statement.

{{11}}: Preferably slowly and painfully …

{{12}}: This was flagged as an issue by the Scottish Government Bee Inspectorate a couple of years ago.

Join the discussion ...