Stings

Don’t you get stung a lot?

If I got £1 for every time I’ve been asked that I would be a wealthy beekeeper {{1}}.

Other than making honey, about the only thing you can be certain that a non-beekeeper knows about bees is that they sting.

Some non-beekeepers get really flustered when just one bee gets trapped on the inside of the kitchen window, triggering visions of anaphylactic shock, excruciating pain, all sorts of disfiguring swellings and mainlining anti-histamines.

It’s therefore unsurprising that choosing to open a box containing 30,000 of these deadly insects is considered an act of titanic stupidity, and one that cannot result in anything other than a frenzied attack and the inevitable accompanying ‘world of pain’.

After all that excitement it’s a bit of an anticlimax when I reply … “No, hardly ever.”

With those three words the vision of the plucky beekeeper, plunging into a tornado of enraged insects to relieve them of their hard-won honey reserves, is seriously undermined.

And it’s totally destroyed when I explain that the worst thing I have to deal with is getting a bit sweaty on a hot day.

Not quite so heroic after all … actually, all a bit pedestrian.

Which is exactly how it should be.

Without stings, beekeeping is not straightforward and is (periodically) very hard work, but no more so than all sorts of other hobbies and pastimes. If loads of stings were a necessary part of beekeeping it would be a whole lot less appealing.

And yet …

Hammered

… how many times have you heard – or, these days, more likely read on social media – of beekeepers commenting about ‘getting hammered by the bees today’ ?

Is this a complaint, or are they bragging?

Do they put up with badly behaved colonies because it makes the gentle art of beekeeping just a teensy bit more macho?

Are tales of their heroics part of the ‘sales patter’ they employ when selling honey?

Do they believe, or even promote, the stories about aggressive colonies being better at collecting honey?

Or are they just clumsy, ham-fisted practitioners that conduct colony inspections on totally unsuitable days, compounding things by clattering through the hive, smoking everything hard, flapping their hands, arms and hive tools about carelessly, and leaving a trail of death and destruction behind them?

It could be any of these … but I have my suspicions.

Let’s quickly deal with the link between colony aggression and honey production.

Other than numerous folksy anecdotes, is there any real evidence for this?

I’m not aware of any.

I’ve always suspected that these aggressive colonies, often tucked away in the corner of the apiary or at the far end of the field, are just inspected less frequently.

Fewer inspections means more undisturbed foraging. The queen pheromone levels in the colony remain undiluted, the alarm pheromones remain unreleased. Colony activity – by the guards, nurses and foragers – continues uninterrupted.

The colony needs supering? Add three at once {{2}} and leave them to it …

Yes, they might swarm, but if they don’t you might be pleasantly surprised by the size of the honey crop you get.

But not because the colony is aggressive. Instead, it’s a consequence of the beekeeper’s unwillingness to get ‘hammered by the bees’ every week.

Getting stung

Don’t get me wrong, I do get stung.

Just not very often.

At the beginning of the season, often after acquiring the first sting, I make a mental note to keep count of the number of times it happens during the season.

Without exception I promptly forget by the time I leave the apiary. The pain has gone and I’ve got other things to think about {{3}}.

Although I’ve never managed to keep count I’d be surprised if it’s many more than half a dozen times. It’s so infrequent it sometimes gets a mention in my hive notes.

This season I’ve opened hives ~350 times. That’s pretty typical for the last decade. Not every one of these was a full inspection, but it includes inspections, supering, queen rearing, uniting, shook swarms, requeening, miticide treatment, feeding etc. Not all were full-sized hives; this number also includes quite a few nucs (but not mini-nucs which are supinely passive anyway).

Of course, over the years, there have been a few stings that were memorable, and a few that were really painful.

A sting on my lower lip – ironically while walking past the apiary with no opened hives – produced a BAFTA-nominated Joseph Merrick impression, more distressing for my family than it was for me, though I did feel pretty ropey for a couple of days. I now take care to (almost) always wear a veil when opening hives.

I also once dropped a clump of bees into the top of my boot which prompted a frantic, expletive-laden, one-legged dance but rather fewer stings than I deserved.

Soft tissue stings (inner arm, thigh {{4}} ) always hurt for longer.

Not getting stung

Not getting stung involves a combination of the bees and beekeeping.

Good i.e. calm and well mannered bees inspected by a calm and careful beekeeper {{5}} makes for a pain-free experience for everyone involved.

This is something I’ve worked at over the years.

The bees

I’m careful to record two relevant characteristics – temper and following – every time I open a colony.

Temper refers to direct aggression – pinging off my veil as I stand over the hive, jumping up off the frames when I pass a hand over the top bars.

Following is different. If I’ve closed up a colony and the bees continue to pester me, for example after walking away to the shed, they are ‘followers’.

I suspect the two traits are genetically distinct – not all defensive/aggressive colonies follow, and you sometimes get followers even when a colony is relatively passive.

Neither characteristic is tolerated unless there are extenuating circumstances e.g. it’s cold and raining or the hive has been heavily manipulated (such as a shook swarm) … or I did something stupid like dropping a frame.

Identifying a colony that follows is tricky if you have many hives in your apiary. I try to open the colonies in a different order each week in the hope I can identify the culprits.

In reality, I now rarely see colonies with either trait. It only takes a few seasons to significantly improve the quality of your stock.

Cull the worst and only use the best for rearing new queens.

This process does not need to involve grafting, bloated, towering cell starters and mini-nucs. It can be as simple as removing the queen from a dodgy colony, returning a week later to knock off all the queen cells and then adding a frame of eggs and larvae from a good colony.

A month later you should have a good new mated, laying queen.

Finally, remove drone brood from tetchy colonies before it has a chance to contaminate the local gene pool.

The beekeeping

It probably doesn’t matter how good your beekeeping is if the bees are psychopaths. Conversely, a clumsy, inattentive and sloppy beekeeper will bring out the worst in the calmest of bees.

Dress appropriately for the conditions. This might mean a veil, a veiled jacket or a full beesuit.

The conditions includes both environmental and the colony being inspected. In poor weather or with a stroppy colony you’ll probably need to be wearing more … as much for the confidence it provides as the physical protection.

A bad tempered colony, a low pressure system bowling in from the west, squally hail showers or thunder and lightning might necessitate a jacket over the beesuit, and a thick fleece underneath it.

You’d be wiser staying at home.

One of the Eureka! moments in beekeeping is realising that thinner gloves are preferable to huge, clumsy, welders gauntlets.

Marigold washing up gloves are pretty good, but thin nitriles are even better. If you can feel the bees with your fingers you’re well on your way to not crushing them, and consequently the colony will remain calmer.

A sting just about penetrates a nitrile glove or thinly stretched Marigold, but the barbs will not get embedded in your hand. Either will provide ample protection and will significantly increase your dexterity and – because they are essentially disposable – your apiary hygiene.

Like Team Sky’s ‘marginal gains’, improved inspections involve lots of little things – use of the hive tool, frame handling, the smoker, being firm but gentle, confidence, speed etc.

Practice makes perfect.

Doing a couple of dozen inspections in a season will improve things, if you do a couple of gross you will improve faster.

A tale of the sting

Being ‘stung’ by a bee – or a wasp, an ant or a hornet – involves two things.

The stinging organ and the venom proteins that are injected.

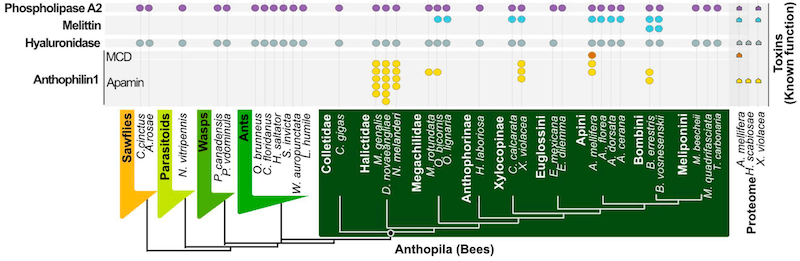

The stinger (the delivery system) evolved long before bees were bees as the ovipositor that was used to co-inject immunomodulatory ‘venoms’ together with eggs into plant hosts. The extant sawflies still do this, at least 120 million years later.

The smorgasbord of proteins injected are termed venom proteins but, confusingly, only the proteins with direct venomous activity are termed toxins. Those that are not toxins are sometimes termed venom-associated proteins. Many of the venom proteins are allergens (see Spillner et al., 2014).

Recent comparative genetic studies (Koludarov et al., 2023) have shown that venom-associated proteins are widely shared between the majority of aculeates (stinging insects) {{6}}, most of which belong to the Hymenoptera – the bees, ants, sawflies, parasitoid and true wasps.

This genetic conservation indicates that the protein constituents of the sting existed before the evolution of eusociality and before the evolution of the aculeate stinger from the ovipositor.

Two of the toxins are also widely distributed; phospholipase A2 and hyaluronidase. Actually, these proteins are very widely distributed (e.g. humans have both) as they perform the basic cellular functions of degrading fatty acids or hyaluronic acid.

The bee-specific toxins are mellitin and apamin. Both are short peptides of 26 or 18 amino acids respectively. Apamin is a neurotoxin and mellitin is cytotoxic (cell killing) and the primary reason stings are painful (Chen et al., 2016).

Painful … and sometimes fatal

Studies suggest that ~95% of the population get stung during their lifetime. Irrespective of the insect they are stung by – which is usually not recorded anyway – the vast majority only experience normal or large local reactions; localised swelling, redness and pain.

See also: I discuss the pain associated with stings – and the IgNobel-winning Schmidt Insect Pain Index – in an earlier post, Ouch, that hurt!

Only in rare instances does the individual experience systemic anaphylactic reactions or – in the case of many stings – systemic toxic reactions, either of which may be fatal.

Insect stings account for ~50% of all anaphylactic reactions, all of which are serious but not all of which are fatal.

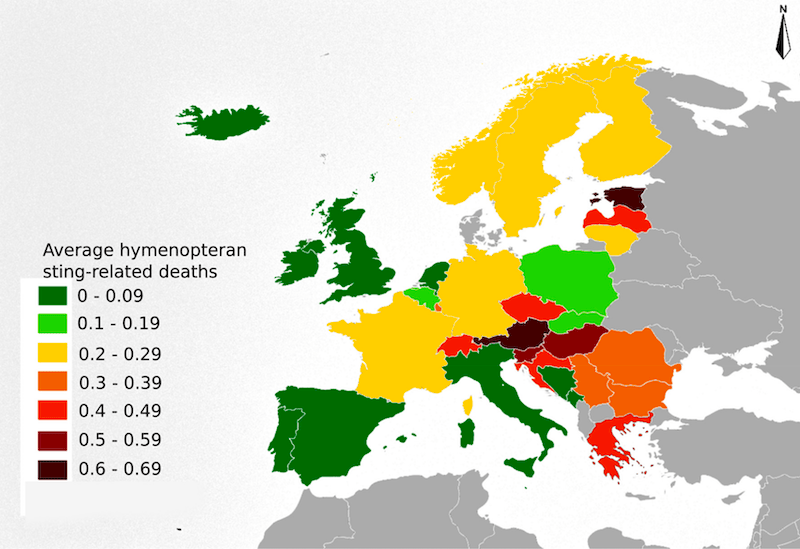

In the 23 year period (1994 – 2016) there were 1691 deaths in Europe attributed to bee, wasp and hornet stings {{7}}, an average of ~73/annum (Feás et al., 2022). Over the same period there were 51 deaths in the UK (~3.4/annum). For comparison, it has been estimated that there are ~60 deaths/annum from bee, wasp or hornet stings in the USA.

Almost 80% of deaths are of males and >95% are of adults over 25 years old. This uneven distribution probably mainly reflects exposure risk although mastocytosis, a rare condition that predisposes for venom allergies, is more common in males.

Whilst obviously individually tragic, insect stings are a very rare cause of death and are estimated to account for only 0.03-0.48 fatalities per million per annum.

However, these numbers may well increase.

Alien species

A second study by Feás (2021) investigated bee, wasp or hornet sting-related deaths in Spain.

Although hampered by the same lack of identity of the specific stinging insect the paper includes additional comments on the impact made following the introduction of the Asian hornet (Vespa velutina).

Between 2014 and 2018 at least 8 deaths (of the 29 total) were likely due to the Asian hornet, and the annual mortality rate over a 20 year period – of which the last 8 years corresponded with the presence of the Asian hornet in Spain – increased ~40%. The numbers still remain very low (~0.1/million of the population), but they are increasing.

In 2020 a further 4 Spanish fatalities were attributed to the Asian hornet. This is one of three non-native hymenopterans newly introduced to Europe in the last few years; Vespa velutina (Asian hornet) in 2004, Vespa bicolor (Black shield hornet) in 2013 and Polistes major major (American paper wasp) in 2008.

In addition, other species are being translocated within Europe and so increasing their range. Vespa orientalis (Oriental hornet), originally introduced to south-eastern Europe, is now found in Spain, France, Romania and Italy (where it is currently causing a ‘plague’ in Rome). Similarly, social wasps belonging to the genera Vespula and Dolichovespula have recently been found in Iceland, Shetland, Orkney and the Faroe Islands.

More species + increased range = more stings.

It’s worth remembering that the anaphylactic reactions are species, or at least genera, specific. You can be unaffected by stings from honey bees and yet develop a severe anaphylactic reaction to an Asian hornet sting.

Take care.

Notes

Although my Joseph Merrick impersonation was only nominated, David Lynch’s biographical drama about Joseph Merrick, The Elephant Man, won the best film BAFTA in 1980. This was Lynch’s second film and a whole lot more mainstream and accessible than his, frankly weird, debut Eraserhead.

The Deadly Bees was a 1967 cult horror film starring (amongst others) Suzanna Leigh and Frank Finlay. Finlay’s character (Manfred), a beekeeper, claims to control his bees via a tape recording of a high note made by a death’s-head moth, which hypnotizes them … if only it were so simple.

References

Chen, J., Guan, S.-M., Sun, W., and Fu, H. (2016) Melittin, the Major Pain-Producing Substance of Bee Venom. Neurosci Bull 32: 265–272 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-016-0024-y.

Feás, X. (2021) Human Fatalities Caused by Hornet, Wasp and Bee Stings in Spain: Epidemiology at State and Sub-State Level from 1999 to 2018. Biology 10: 73 https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/10/2/73.

Feás, X., Vidal, C., and Remesar, S. (2022) What We Know about Sting-Related Deaths? Human Fatalities Caused by Hornet, Wasp and Bee Stings in Europe (1994–2016). Biology 11: 282 https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/11/2/282.

Koludarov, I., Velasque, M., Senoner, T., Timm, T., Greve, C., Hamadou, A.B., et al. (2023) Prevalent bee venom genes evolved before the aculeate stinger and eusociality. BMC Biology 21: 229 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-023-01656-5.

Spillner, E., Blank, S., and Jakob, T. (2014) Hymenoptera Allergens: From Venom to “Venome.” Frontiers in Immunology 5 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00077.

{{1}}: Or, more accurately, a little bit less broke than I am having recently purchased yet another big stainless steel thingy for my beekeeping.

{{2}}: Quickly!

{{3}}: And am forgetful … now, where was I?

{{4}}: Or higher!

{{5}}: Manners are irrelevant.

{{6}}: From the Latin acūleātus meaning insects that sting, but also applied to the spines/rays of fish, or prickles of plants.

{{7}}: There’s a WHO mortality database where these sort of things are recorded.

Join the discussion ...