The bees know best

Synopsis : Queens reared under the emergency response are numerous and preferentially started from eggs. The cells are then subjected to strong selection by workers after capping. What does this tell us about good quality queens and can we use this knowledge to improve our own queen rearing?

Introduction

In Eats, sleeps, bees I made a passing comment on the confidence I have in the ability of bees to choose ‘good’ larvae when rearing a new queen. I was justifying why I only leave a single queen cell in a colony that needs requeening. The precise words were:

“I also had total confidence that the bees had selected a suitable larva to raise as a queen in the first place. After all, the survival of the resulting colony depends on it.”

I thought this might be an interesting topic to look at in a little more detail. There is some interesting science on queen cell production.

And subsequent destruction.

In addition, there are related observations on what the bees choose as the starting material for queen cells. This should inform our own queen rearing activities. I’ll discuss these (briefly) after presenting the science.

Emergency, supersedure and swarm responses

But first I need introduce the three ‘responses’ under which a colony rears one or more new queens. These are the emergency, supersedure and swarming responses {{1}}

The swarming response

Around this time of the season {{2}} many beekeepers will be familiar with queen cells produced under the impulse to swarm.

A strong, queenright colony runs out of space. Eggs are laid in specially created vertically oriented cells and are subsequently reared as new queens.

Once these swarm cells are sealed the colony swarms. The old queen and a significant proportion of the workers disappear over the fence. One or more new queens emerge and the colony may produce casts, each headed by a virgin queen. One new queen finally remains, gets mated and heads the original colony.

Swarming is honey bee reproduction … it is the only (natural) way one colony becomes two.

The supersedure response

Supersedure is the in situ replacement of the current queen. The colony produces a small number of supersedure cells – often just one, located in the middle of a central frame {{3}} – the new queen emerges, mates and starts laying. There may be two queens in the box for an extended period, but eventually the old queen disappears.

Supersedure is probably more common than most beekeepers think. It is the usual explanation for the presence of an unmarked queen at an early season inspection in a hive that had previously contained a marked queen.

The emergency response

If the incumbent queen is removed or killed the colony must rear another or they are doomed. They do this under the emergency response.

Some beekeepers – particularly beginners {{4}} – inadvertently crush the queen while returning brood frames. They are then surprised at the next inspection to find no eggs but a lot of queen cells.

What’s this? Swarming finished weeks ago!

This is the emergency response at work. The bees select several suitable eggs or larvae, reshape the comb to allow a vertically-oriented cell to be drawn and feed with copious amounts of Royal Jelly.

And voilà, a new queen {{5}} is produced.

Inducing these responses

The emergency response is triggered by the removal of the old queen – either by physically taking her out of the box, or killing her. Both are easy to achieve 🙁 {{6}}

There are ways to induce a supersedure response, but they sometimes involve damaging the queen {{7}} and are unreliable and – more importantly – ethically dubious. There are more ethically acceptable alternatives.

Lots of beekeepers inadvertently induce the swarming response by not providing the bees with sufficient space, not supering early enough or allowing the brood nest to be backfilled with nectar.

However, doing this in a controlled manner is not a certainty. In one of my apiaries 50% of the colonies have shown no inclination to swarm this season whereas the others all produced swarm cells. All were treated similarly and were – to all intents and purposes – of equivalent strength.

For scientific purposes inducing a swarming response cannot be relied upon for studies of queen cell production and selection.

In contrast, the emergency response is 100% reliable. Therefore, in the majority of studies on brood choice, queen cell production and selection, it’s the emergency response that is exploited. That’s certainly the case with the two papers I’m going to briefly discuss this week. {{8}}.

Pick a larva, any larva

Is that what the bees do?

Of course not.

Regular readers will remember from Timing is everything that only larva up to three days old are suitable for producing new queens i.e. six days after the egg is laid.

However, if the queen is laying 1000 eggs per day {{9}} that still means there are up to 3000 suitably aged larvae in the hive for the production of a new queen, should one be needed.

Actually there’s even more choice as the bees can start the queen rearing process – the production of a queen cell – from a cell occupied by an egg … something that has been known for decades, but is relatively rarely discussed.

So, what do they choose?

The first study I’m going to discuss addresses this point and the interesting (and critical) aspect of the quality of the resulting queens that are produced.

Hatch, S., Tarpy, D. & Fletcher, D. Worker regulation of emergency queen rearing in honey bee colonies and the resultant variation in queen quality. Insectes soc. 46, 372–377 (1999).

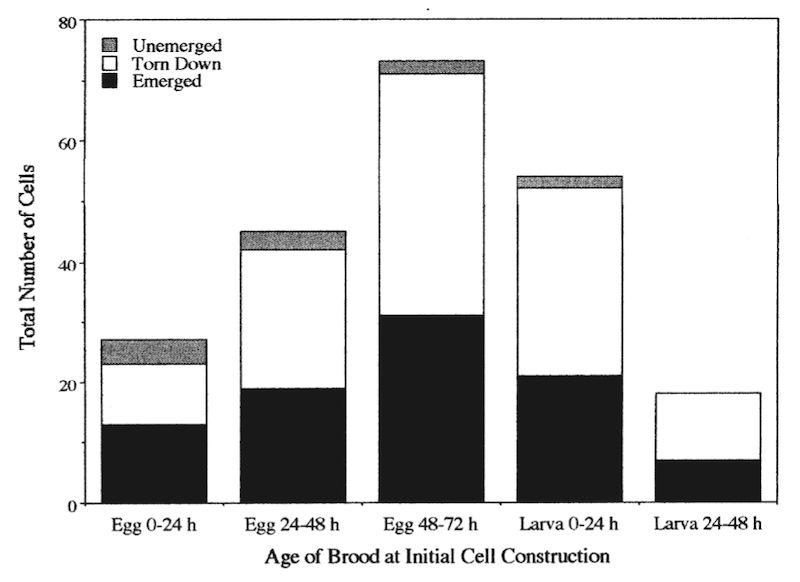

The study was very straightforward. They induced the emergency response by dequeening strong hives. They then monitored the production and position of queen cells over time, determining the age of the egg/larvae selected by extrapolating back from the day the queen cell was sealed.

Cells that were capped were caged with queen excluder and the resulting emerged queen was analysed to determine her quality. This essentially involved determining her size and weight (the bigger the better) and ovarial number, but they measured additional features as well.

Emergency cell production

In the 8 colonies used, almost all queen cell construction was started within 24 hours of queen removal. A few more cells were produced for up to 48 hours after dequeening, but none were started after that.

There will still be many hundreds of (apparently) suitably aged larvae in the colony at this point. However, these were not selected as all the queen cells that would be made had already been started.

Colonies produced different numbers of queen cells, from 6 to 56 (average 27).

However, the majority of these cells were torn down before emergence, and a few of those that were sealed never emerged. Of the 217 cells started, 115 (53%) were torn down, 11 (5%) did not emerge and the remaining 91 (43%) emerged.

Not only did the number of queen cells produced vary greatly between hives, so did the numbers of queens that emerged – from 3 to 20 (average 11).

The brood nest is roughly spherical or rugby ball-shaped and usually occupies the centre of the hive. About 46% of the cells started were on the central three frames, and these had a much greater chance of producing queens. This was because queen cells started on the central frames of the brood nest were less likely to be torn down (41%) than those on the periphery (71%).

Pick an egg or a larva (in which case, the younger the better)

So if it’s not ‘Pick a larva, any larva’, what do the bees choose to start their emergency queen cells from?

Remember how important this is. Without a new queen the colony cannot survive. The clock is ticking. They only have a few days to make this choice before all the brood in the nest are too old for queen production.

They predominantly choose eggs.

Almost 70% of queen cells started were initiated when the cell contained an egg, rather than a larva. What’s more, the majority of the eggs chosen were three days old.

If you consider that there were 6 possible choices (1, 2 or 3 day old eggs and 1, 2 and 3 day old larvae), it’s striking that 34% of all the queen cells produced were from 3 day old eggs.

In fact, it turns out that only five choices were made as none of the queen cells were started from 3 day old larvae.

Furthermore, over 60% of queen cells produced from 2 day old larvae were subsequently torn down.

Bees choose to make queens from the oldest eggs or the very youngest larvae.

Are you getting the message?

Since the production of a new queen is essential for colony survival we should assume that the bees have evolved a queen cell production ‘strategy’ that maximises the chances of producing a suitable queen.

Almost 60% of the ‘starting material’ chosen by the bees to ensure colony survival – that resulted in queen production – were 3 day old eggs or 1 day old larvae.

This emphasises the need to provide colonies we use for queen rearing with eggs and larvae of this age range. It also reinforces the importance of only selecting the smallest larvae possible when grafting.

The choice the bees make is presumably because queens reared from older larvae are of poorer quality, perhaps because they have a reduced period for feeding with Royal Jelly.

So how do the queens produced from eggs and young larvae compare?

Queen ‘quality’

Of the 91 queens that emerged only 89 were analysed because two ”escaped capture”.

It’s reassuring to know that it’s not just cackhanded beekeepers that make mistakes 😉

There were no differences in the morphology – weight or size – for queens that emerged from cells on either the central or peripheral frames {{10}}.

However, queens reared from 3 day old eggs were significantly heavier than queens reared from larvae. In addition, queens reared from 3 day old eggs had a longer thorax than queens reared from either younger eggs or larvae.

Other morphological measurement – e.g. wing length or width – did not differ significantly between queens reared from eggs or larvae.

But are these hefty, long-thoraxed, queens better quality?

This isn’t a simple question. What does better quality mean? It’s not the size or productivity of the resulting colony she heads since that is also influenced by the genetics and number of drones she mates with.

It’s also time consuming and impractical to measure scientifically (for 89 queens).

Instead, the scientists measured the number of ovarioles and the volume of the spermatheca as potential indicators of fecundity. There was no relationship between weight and ovariole number, irrespective of the age of the egg or larva when the cell was started.

If not more fecund, what?

So, if bigger queens don’t necessarily have increased fecundity (though remember, this wasn’t shown – all they demonstrated was that the ‘innards’ involved in fertilised egg production were similar) why might the bees select eggs/larvae that resulted in bigger queens being produced?

One possibility is that these bigger queens have greater success in what is termed polygyny reduction.

This is what beekeepers call fighting.

If more than one queen is present they fight until only one is left in the hive. This hadn’t been extensively studied in 1999 (when this paper was published) but has been addressed in other studies {{11}}.

Alternatively, and suggested in a tempting but cryptic ’unpublished data’, heavier queens may be able to achieve higher levels of polyandry i.e. mate with more drones, so increasing the genetic diversity, and consequently the fitness, of the colony. I’ve discussed the importance of polyandry and so-called hyperpolyandry for colony fitness and disease resistance previously, so won’t revisit these here.

It’s easy to speculate that a queen with a larger thorax may have better developed flight muscles. These might enable her to stay longer in drone congregation areas for mating.

Why are so many cells started (and queens reared)?

In the emergency response only one queen is needed to ‘rescue’ the colony from oblivion.

Why therefore are so many queen cells – on average 27 per colony – started?

And why do the workers allow an average of 11 queens emerge?

The authors suggest a number of possible reasons:

- Colonies raise multiple queens to guarantee the requeening process. This assumes that the ‘cost’ of queen rearing is low, which seems reasonable. Since only 5% of queens raised failed to emerge it is probably not to overcome this limitation.

- Multiple queens allow colony reproduction if conditions are suitable. Only colonies that raise multiple queens would be able to (simultaneously) reproduce and requeen, so there might be a selective pressure to allow this.

- A consequence of age demographics (brood or workers) in the colony. This is slightly trickier to explain and has not been tested. Queen cells result from an ‘interaction’ of available brood (eggs/larvae) with workers. A colony has variable numbers of both, and there are a variety of worker cohorts, only some of which contribute to cell building. Therefore, the production of multiple cells (and queens) may simply reflect the variation in the factors – ages of brood and workers – involved.

- Rearing multiple queens allows workers to select the ‘best’. That’s clearly wrong because the ‘best’ would be just one queen. Perhaps a better explanation would be that it allows workers to either select for better queens by destroying those that are less good.

No single reason

Biology is complicated {{12}} and it may be that all four of the reasons above are correct. There may be (and almost certainly are) additional reasons that favour the production of multiple queens.

However, of the four reasons above, this paper provides nearly compelling evidence that the workers are selecting which emerge and which do not.

Remember, 53% of the cells that were started were torn down.

In addition, there was both a spatial and temporal bias to the cells that were torn down. This strongly suggests that the process (of cell destruction) was not random.

However, it remains only nearly compelling because we know nothing about the queens that were in cells that were torn down.

By definition those queens don’t exist. The cells were torn down and the queens killed/eaten/discarded so we have no measure of their quality.

If they were indistinguishable from those that did emerge then I’d struggle to convince you that the worker selection was producing ‘better queens’ from the large number of queen cells that were started.

Analysing the non-existent

But fortunately this experiment has been done.

Tarpy, D.R., Simone-Finstrom, M. & Linksvayer, T.A. Honey bee colonies regulate queen reproductive traits by controlling which queens survive to adulthood. Insect. Soc. 63, 169–174 (2016).

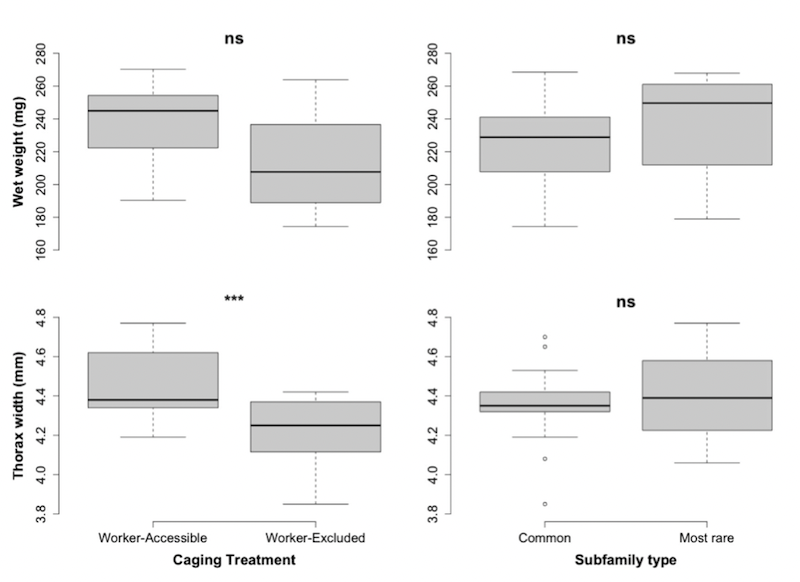

The experimental methods were almost identical. However, this time, when they caged the capped queen cells they randomly assigned them to cages that either allowed or prevented worker access (both types of cages prevented the escape of the queen).

They then analysed the queens that emerged from the ‘worker-accessible’ and ‘worker-excluded’ queen cells.

The hypothesis was straightforward, if the workers were randomly destroying a proportion of queen cells there would be no differences in the characteristics of the resulting queens. Conversely, if there was selection, the queens from the ‘worker-excluded’ cells would be different.

The overall numbers of queen cells produced (average 12, range 4 – 22 per colony) and the proportion – 57% – of the ‘worker-accessible’ cells torn down were similar to the study I’ve already described.

‘Worker-excluded’ queens were significantly smaller than those from ‘worker-accessible’ cages. They also weighed less. This is obvious from the top left panel (above) but confounded {{13}} by the small size of the study and the significant differences in the weight of queens produced in different colonies {{14}}.

Despite the limited size of this study these results strongly suggest that workers are somehow ‘weeding out’ lower quality (defined here as smaller and probably lighter) queens.

I’ll leave it to you to speculate on how the workers outside the queen cell determine the size/weight/quality of the queen inside the cell … 😉

Does this have relevance to beekeeping?

I think there are a number of interesting points from this study that have relevance to practical beekeeping.

- Queen cells were started under the emergency response only in the first 3 days after the queen was removed. The vast majority were started within 24 hours. This should help determine when the queen went missing or – if you deliberately removed her – defines the latest date that you need to be concerned about new cells being started.

- If you are improving your stocks by adding larvae from a separate colony {{15}} then make sure you add a frame containing eggs and larvae. You want to be sure they have access to 3 day old eggs.

- It probably makes sense to place this frame in the centre of the brood nest.

- If you’re grafting larvae for queen rearing – as I’ve already suggested – make sure you choose those under ~18 hours old. The younger and the smaller the better.

- But, perhaps we should instead think about grafting eggs rather than larvae?

This last suggestion is a topic of a (part-written) future post.

Here are a couple of additional points to think about. Studies have shown that egg transfer results in the largest queens. However, eggs are accepted significantly less well than larvae … and some colonies will not accept them at all. I’ll discuss this in more detail some other time.

And a final caveat …

The final point to remember is that both these studies analysed queen cell production and the resulting queens under the emergency response.

Many queen rearing methods – the so-called ‘queenright’ ones such as my favoured Ben Harden method – exploit the supersedure response. It’s always possible that the bees have different preferences for queens reared under the supersedure (or for that matter the swarming) responses.

But I doubt it 😉

After all … colony survival is dependent upon good quality queens and the bees know best.

{{1}}: See this post as well for more details.

{{2}}: Usual caveats apply … I’m writing this in the Northern hemisphere as we segue from spring to summer.

{{3}}: But don’t rely on this!

{{4}}: Though not exclusively … ahem!

{{5}}: Or several as you will see below.

{{6}}: As an aside, I can’t think of a frequent and natural cause of sudden queen disappearance from a hive. Disease perhaps, but injury or sudden death seems unlikely. What have I forgotten?

{{7}}: Removal of a leg, for example.

{{8}}: I’ll briefly return to any relevance to the supersedure and swarming responses, and to queen rearing at the end.

{{9}}: A conservative estimate for May and June.

{{10}}: After age matching those started from eggs or larvae.

{{11}}: The enthusiastic could read this for starters, but I’ll probably deal with it sometime in the future.

{{12}}: Which quite neatly summarises my career.

{{13}}: In terms of statistical significance.

{{14}}: Only 33 queens were reared overall, 15 in ‘worker-excluded’ and 18 in ‘worker-accessible’ cages.

{{15}}: Having destroyed all the queen cells produced from the previous queen’s brood.

Join the discussion ...