Eats, sleeps, bees

Synopsis : The beekeeping season is starting to get busy. Swarm control is not only essential to keep your hives productive, but also offers easy opportunities to improve the quality of your bees. Good records and a choice of bees is all you need. This week I discuss stock improvement together with a few semi-random thoughts on honey labelling, colony behaviour and wax foundation. Something for everyone. Perhaps.

Introduction

May is usually a lovely month in Scotland. It is often dry and sunny enough to spend much of the time outdoors, the days are long enough {{1}} to get a lot done and it’s early enough in the year to avoid the dreaded midges {{2}}.

Usually and often.

Unfortunately, the weather so far this month has been unseasonably cool. It was probably better for much of March than it’s been for the first half of May.

But that good weather in March gave the bees a real boost – particularly in my apiaries on the east coast of Scotland.

Consequently, there’s still a lot of beekeeping to do now – swarm control, preparations for queen rearing, catching up with all the things I didn’t do in the winter ( 🙁 ) – often in between some rather iffy weather {{3}}.

The next couple of months are usually pretty much full on … hence Eats, sleeps, bees {{4}}.

Latitude …

The differences I discussed in Latitude and longitude a month ago are particularly marked now.

Beekeepers in Sussex or Kent have been complaining about running out of supers since mid-April. Other have been proudly displaying their first (or second) round of grafted queen cells.

In contrast, a few of my west coast colonies are still only on 6-7 frames of brood. It will be at least another fortnight until I even think about whether they’ll need swarm control.

Which might be a fortnight before they’ll actually need it.

These are perfectly healthy west coast native bees, adapted to the climate and forage available here.

They are classic late developers, evolution having timed colony expansion to fit with the local forage and the availability of weather good enough for queen mating.

There’s insufficient forage to produce oodles of brood in late April and many colonies have yet to produce any mature drones (though they all now have drone brood). Instead, they build up rather slowly, and are probably at the peak in July when the heather starts to yield.

This is all reasonably new to me and I feel I’m still learning how the season develops here on the west coast. I’m sure I’ll get the hang of it.

Eventually 😉

Going by the rate colonies are currently building up, and their performance last year, I expect to be rearing queens from these colonies in June and early July {{5}}.

… and longitude

Meanwhile, in Fife things are progressing much faster.

My apiaries there are about 160 miles east and at a similar latitude, but most of the colonies are already overflowing their boxes. Swarm prevention is a distant memory and I’m now busy with swarm control.

The genetics are different. My east coast bees are all local mongrels, again adapted to local conditions.

However, I suspect an even greater difference is the early season forage and – although it’ll be finished in the next week or so – the oil seed rape (OSR).

The OSR gives colonies a massive boost. They gorge on it – both the nectar and pollen – quickly filling supers and a multitude of hungry larval mouths. Reasonably strong nucs made up for swarm control on the 1st of May are now in a full brood box and will be more than ready for the summer nectar flow when it starts.

Queen rearing would have started already if the two boxes I’d earmarked for cell raising hadn’t become a little overcooked and produced queen cells at the beginning of the month 🙁 .

The best laid plans etc. {{6}}.

And, to add insult to injury, the (lovely quality) colony I’d intended to source larvae from produced queen cells the following week.

D’oh!

Quality control

One of the (nominal) cell raising colonies – we’ll call it colony #6 for convenience {{7}} was borderline in terms of temperament.

On a balmy afternoon, with a good nectar flow, the bees were calm, unflustered and a pleasure to handle.

However in cool, damp or blustery weather they weren’t so great.

This is one of the reasons that record keeping is so important. Although I’d not inspected them this season in very poor conditions {{8}}, my records from last year also showed they were, shall we say, ’suboptimal’. Not psychotic or even hugely aggressive, but certainly hotter than I’d prefer and nothing like as stable on the comb as I like {{9}}.

Of course, the simple answer is not to go burrowing through the box in ‘cool, damp or blustery weather’ 🙂

However, I don’t always have a choice as these bees are 160 miles away. Met Office forecasts are good for tomorrow, questionable for next week and essentially guesswork for next month (which is when I’m booking the hotels).

So, having realised that both swarm control and quality control were needed, how have I tried to improve the quality of this colony?

Controlling quality

I discovered open, charged queen cells in colony #6 on the 1st of May. Without intervention the colony would have swarmed before the end of the first week of the month {{10}}. The queen was clipped but, as I hope I made clear last week, queen clipping does not stop swarming.

Swarm control

I used my preferred swarm control method by making up a nuc with the old queen and a couple of frames of emerging brood with the adhering bees. I put these, together with a frame of stores and a couple of new frames into a nuc box and moved them to an out apiary several miles away.

By moving the nuc away I don’t have to worry about losing bees back to the original hive. I can therefore make the nuc up a little weaker than I would otherwise need to. An out apiary (or two) isn’t essential, but it makes some tasks a lot easier.

I then went carefully through colony #6, shaking all the bees off each frame and destroying every queen cell. There were still eggs and young larvae present, so they would undoubtedly make more queen cells before my visit a week later. However, by shaking every frame and being rigorous about destroying every queen cell I ensured:

- there would be a bit less work to do the following week

- I’d not missed a more mature cell somewhere that could have left a virgin queen running about at my next visit. This was unlikely, based upon the timing of brood development, but it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Colony #6 is in a double brood box. While ransacking the brood nest for queen cells I also hoiked out a frame of drone brood and cut out yet more drone brood from a foundationless frame or two. Since the genetics of this colony was questionable it made sense to try and stop these undesirable genes being spread far and wide.

At the same time I rearranged the frames, moving all the unsealed brood into the top box.

One week later

Early on the morning of the 8th of May I checked the colony again. As expected there were more queen cells reared from eggs and larvae I’d left the week before.

The vast majority of these queen cells were in the top box, but – since I’m a belt and braces beekeeper – I checked the bottom box as well. Again, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

All of the queen cells were again destroyed.

Tough love … but if you want to improve the quality of your bees you have to exclude those with undesirable characteristics.

Importantly, by now the youngest larvae in the colony would be at least four days old. This is really too old – at least given the choice (and I was going to give them a choice) – to rear a new queen from.

I rearranged the frames, leaving a gap in the middle of the top box, closed colony #6 up and completed my inspection of the other colonies in the apiary.

The last colony I checked was my chosen ‘donor’ colony with desirable genetics.

More swarm control 🙂 and a few days saved

The donor colony (#7) had started queen cells sometime during the first week of May and so also needed swarm control. However, very conveniently it had produced two nice looking cells on separate frames.

Both these queen cells were 3-4 days old and so would be capped in the next 24-48 hours.

I could therefore use my standard nucleus swarm control (to ‘save’ the queen ‘just in case’), leaving one queen cell in colony #7 and donating the other queen cell to colony #6.

Which is exactly what I did.

Having gently brushed off the adhering bees from the frame (you should never vigorously shake a frame containing a queen cell you want {{11}} ) I gently slotted it into the gap I’d left in the upper brood box of colony #6. I also marked the frame to make my subsequent check (on the 15th) easier.

By adding a well developed, but unsealed, queen cell to colony #6 I’ve saved the few days they would have taken to rear a queen from an egg or a day old larva.

Because the cell was open I was certain it was ‘charged’ i.e. it contained a fat larva sitting contentedly in a deep bed of Royal Jelly {{12}}.

Better to be safe than sorry (again)

There were also eggs and a few larvae on the frame containing the queen cell (which was otherwise largely filled with sealed brood). It was likely that some of these would also be selected to rear new queens.

And they were when I checked on the 15th.

There was my chosen – and now nicely sculpted and sealed – cell and a few less well developed cells on the donated frame.

I know the cell I selected was charged and the larva well nourished.

In addition, I also had total confidence that the bees had selected a suitable larva to raise as a queen in the first place. After all, the survival of the resulting colony depends on it.

Therefore, I didn’t need any backups.

Rather than risking multiple queens emerging and fighting, or the strong colony throwing casts, I (again) destroyed all but the cell I had originally selected.

I’m writing this on the 17th and she should have emerged today … so my records carry a note to check for a laying queen during my first inspection in June.

This shows how simple and easy stock improvement can be.

No grafting, no Nicot cages, no mini-nucs and almost no colony manipulations etc. Instead, just an appreciation of the timings and the availability of a frame from a good colony (and this could be from a friend who has lovely bees … ).

And in between all that

That was about 1400 words on requeening one colony 🙁 . That was not quite what I intended when I sat down to write a post entitled Eats, sleeps, bees.

My east coast beekeeping – including 8-9 hours driving – takes a couple of days a week at this time of the season. On the west coast I have fewer colonies and – as outlined above – they are less well advanced, so there’s a bit less to do {{13}}.

However, there are always additional bee-related activities that appear to fill in the gaps between active colony inspections.

I’ll end this post with a few random and half thought out comments or questions on stuff that’s been entertaining or infuriating me in the last week or so.

In between the writing, inspections, Teams meetings, editing, reviewing and writing … 😉

Honey labelling

I use a simple black and white thermal printer – a Dymo LabelWriter 450 – to produce labels that don’t detract from (or obscure) the jar contents.

I’ve used these for over 6 years and been very happy with the:

- cost of the labels (a few pence per jar)

- flexibility of the system. I can change the best before date, the batch number or other details for each print run; whether it’s 1 or 1000.

- ability to include QR codes containing embedded information, like a website address or details of the particular batch of honey.

However Dymo, in their never ending quest for more profits a ‘better consumer experience’ have recently upgraded their printers and label printing software {{14}}.

The newest incarnation of the printer I use – now the Dymo LabelWriter 550 – only works with authentic Dymo labels.

A more accurate spelling of authentic is e x p e n s i v e , at least if you only buy labels in small quantities (100’s, not 1000’s).

If you fancied adding a little square label on the cap of 100 jars claiming ”Delicious RAW honey” you’d not only be falling foul of the Honey Labelling Regulation, you’d also have to cough up £18 for a roll of labels.

Dymo labels are great quality. Smudge proof, easy to remove and sharp black on white. In bulk they are reasonably priced (~3p – the same cost as an anti-tamper label – if you buy >3000 at a time).

However, you can get similar labels for a third of the price … but they won’t be usable in the new printer.

The Dymo LabelWriter 450 has no such restrictions and is still available if you look around.

I’m tempted to buy a spare.

Colony to colony variation

I started this post with a discussion of variation due to latitude and longitude. However, individual colonies in a single location can also show variation (in addition to temperament, running, following etc.) that I don’t really understand.

I have three colonies in a row behind the house here on the west coast. I can see whether they are busy or not when I’m making coffee, doing the washing up or pottering in the work room (two of these activities are more common than the other 😉 ).

And they are consistently different, despite being pretty similar in terms of colony strength and development.

One colony typically starts foraging before the others and another, probably the weakest of the three, forages later and in worse weather.

Early in the season these differences were so marked I thought that one of the colonies had died.

I assume – because a) I’ve not got the imagination to think of other reasons, b) it’s the justification I use for anything I don’t properly comprehend, and c) I’ve not done any experiments to actually test what else it could be – that this is due to genetics.

It’s only because I’m fortunate enough to look out on these colonies dozens of times a day that I’ve noticed these consistent behavioural differences. I suspect my other colonies show it, but that I’ve never looked carefully or frequently enough.

Attractive foundation

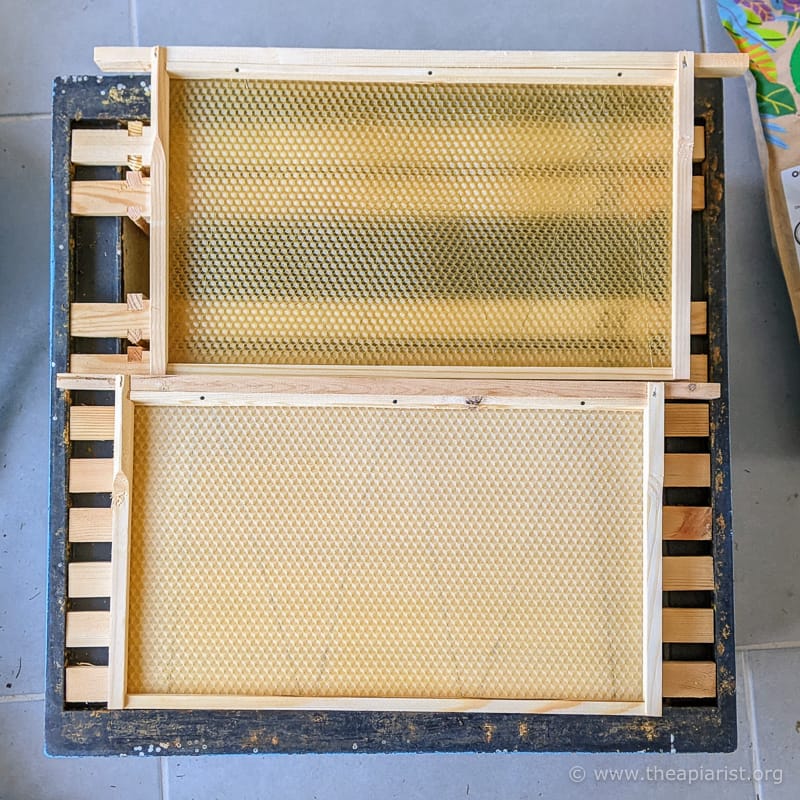

I’m busy making up nucs for swarm control and sale. Although many of the frames I use are foundationless I also use a lot with standard foundation. The frames are built (or should be built!) in the winter, but I add the foundation once the weather improves and there’s less risk of cracking the brittle sheets due to low temperatures.

I buy foundation once every season or so and carefully store it somewhere cool and flat. Some of these sheets are quite old by the time I get round to using them and they often develop a white powdery ‘bloom’ on their surface.

I used to run a hairdryer over the frames containing these bloomed sheets. The warm air brings out the oils in the wax and makes they much more attractive to the bees. They smell great!

These days I just stick a ‘box full’ of frames at a time into my honey warming cabinet set at about 40°C for 30 minutes. Not necessarily quicker, but a whole lot easier … so freeing up time to do something else related to bees 🙂

Note

Today is World Bee Day. The 20th of May was Anton Janša’s (1734-1773) birthday. He was a beekeeper – teaching beekeeping in the Hapsburg court in Vienna – and painter from Carniola (now Slovenia). He promoted migratory beekeeping, painted his hives and invented a stackable hive.

{{1}}: The sun currently rises at 5 am and sets after 9:30 pm.

{{2}}: Which are only really a problem on the west coast during calm, humid days following a damp Spring.

{{3}}: 40 mm of rain yesterday as London basked at 27°C.

{{4}}: Remembering that I not only keep bees, but also lead a research group studying deformed wing virus and chronic bee paralysis virus as well as writing (scientific papers, this site and some other projects) extensively – sometimes too extensively – on them. And talks … don’t forget the talks ;-)

{{5}}: In fact, Morris boards went in the strongest colonies today and I might risk an early round of grafts at the end of next week.

{{6}}: Some Robbie Burns seemed appropriate for a comment on Scottish bees. The original is “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men, Gang aft agley”, from the poem ”To a mouse”.

{{7}}: And because that’s its number … this blog is nothing if not authentic.

{{8}}: Remembering that normal April weather might be 12°C and intermittent rain.

{{9}}: Have you noticed that temper often varies between inspections whereas steadiness on the comb is reasonably consistent? … Runners gotta run.

{{10}}: In retrospect, having looked at the local weather, they would probably have gone on the 4th.

{{11}}: At least, that’s what everyone says, but like everything in beekeeping, there are few absolutes. I’ve previously dropped a frame containing a queen cell, without any apparent adverse effects for the resulting queen.

{{12}}: OK, I’ll admit that the contentedly was anthropomorphic, but you can almost imagine her laying there in the warm, humid atmosphere, troffing hungrily on sickly sweet Royal Jelly and periodically belching. Sorry.

{{13}}: Until there isn’t.

{{14}}: I won’t bother discussing the latter … it’s got some weird bugs in it.

Join the discussion ...