The best laid plans

Writing a ‘sometimes scientific and intermittently anecdotal’ beekeeping blog for a mixed (by geography, ability, experience and interest) audience can be challenging.

The post last Friday, on the comparison of three different management methods, barely registered an uptick in daily page reads. In contrast, the rambling semi-coherent anecdotes shared a fortnight ago went ‘off the scale’, with thousands reading the post on the Friday alone.

Actually, more read it on that Friday than have read the last post on Management comparisons altogether.

Weird … I’d have thought it would be the other way round.

Lots of beekeepers are averse to using ‘hard’ chemicals and here was compelling evidence that they were no better than organic acids. Similarly, there’s a strong ‘treatment-free’ emphasis by some, and here was evidence that it was depressingly unsuccessful in actually keeping colonies alive (when tested to pretty rigorous scientific and ‘real world’ standards).

Nice brood, no stores

Maybe everyone knows and accepts this?

Perhaps the points I emphasised on molecular markers of disease were too nuanced {{1}}.

However, I get the message … I want to write stuff that people want to read, so this week I’ll return to platitudinous anecdotes and homespun homilies (perhaps with a few buried tips, tricks and scientific asides for the observant reader).

Shirtsleeve weather

Beekeeping can be hot and hard work.

Firstly it’s mainly a late spring and summer activity when the temperatures are inevitably higher. We’re often told/read to start inspections when it is “shirtsleeves weather” i.e. warm enough to do away with a coat or jacket.

Secondly, it is often physically demanding, with hives to be shifted and honey-laden supers needing to be removed and replaced without too much jolting or jarring.

Finally, at least for some beekeepers, there’s the fact that the 40,000 denizens of the boxes have the ability to deliver a nasty little sting if provoked, so raising the pulse a little.

All of which means that you can get very hot and sweaty in a beesuit. I therefore usually wear mine over a T shirt and shorts in the summer, trusting the voluminous folds, creases and overly generous fit {{2}} will prevent any stings from penetrating.

And trusting my year-on-year selection of well-tempered bees (and, as important, routine culling of queens heading colonies which have poor temper) to have produced colonies that are not defensive and tolerate my weekly fumblings in the brood box.

But there’s an exception to this and that’s when I have to go though a colony known to be ‘hot’.

Typically these are not my bees, but when I’m helping another beekeeper.

Fleeced

If the owner refuses to assist and instead offers to stay in the kitchen and make a cuppa for my return, if the bees are pinging off my veil as I open the apiary gate, or if a mushroom-shaped cloud of unbridled aggression greets my removal of the crownboard … if any of those situations occur I make a hasty tactical withdrawal and put a thick fleece jacket on under my beesuit.

It’s hot as hell, but no stings can penetrate … I can then do whatever is necessary with total confidence. Of course, what is really necessary is requeening the colony, which is usually what I’m there to do 😉 .

And on Monday I had to wear a fleece under my beesuit … and a beanie {{3}} pulled down over my ears.

Not because the bees were aggressive but because it was so damned cold.

At least it’s not raining

I’d driven across to my east coast apiaries, leaving at silly o’clock to deliver lots of honey en route, and had arrived mid-morning. I had a long list of tasks to complete, the most important of which was to prepare a cell raising colony for the first round of queen rearing.

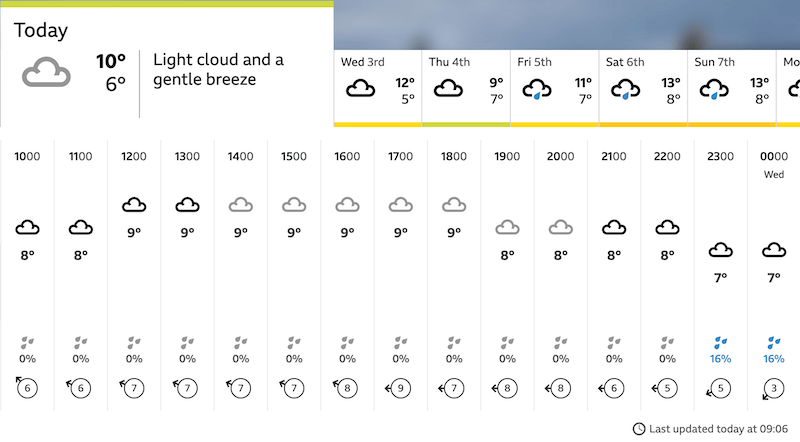

As the miles ticked by I’d expected the temperature to rise. Instead it plateaued in low double figures (°C) and then started to drop as I approached the end of the journey.

By the time I got to the first apiary it was hovering around 9°C.

Not ideal, but them’s the breaks when you have apiaries 150 miles from home and book trips several weeks in advance.

At least it wasn’t raining … yet 🙁 .

Baltic

Low temperature inspections are sometimes a necessary evil. Several of my colonies had been on 8-9 frames of brood at the last inspection and I was expecting swarm preparations in those most advanced.

I was hoping to delay swarm control – almost always done by removing the queen to a nuc – by harvesting a frame or two of brood from half a dozen booming colonies and pooling them to produce a cell raiser for queen rearing.

This is an approach I’d read about over the winter (or perhaps last winter?) in a newsletter from BIBBA {{4}} and I wanted to combine it with a new method (to me) for selecting and presenting larvae to rear as queens.

Low temperatures tend to delay swarming, but the postponement is temporary. As soon as the weather warms, off they go. I wanted to beat them to it … harvesting enough brood to hold them back, without weakening them so much it impacted nectar collection.

Therefore, despite the temperatures being little short of ‘Baltic’, I had to open the boxes.

The bees were impeccably well behaved. No pinging, no stinging, little more than a semi-contented buzz. Perhaps they were all torpid due to the cold?

There were no signs of swarm preparation … and it was soon very obvious why not.

All but the very strongest colonies were dangerously low on stores.

At the last visit the spring nectar flow was just starting. All colonies with 7-8 frames of brood were supered, all had fresh nectar in the brood box and were expanding well.

Disappointingly light … don’t let the supers mislead you

Now, a fortnight later, queens were laying halfheartedly, the supers were empty and the brood boxes were much lighter than they should have been.

For a rainy day

’The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft agley’ {{5}} as Robbie Burns wrote in ’To a Mouse’.

I’d planned to set up my cell raiser but now had to find a solution to a different problem altogether.

Fortunately, I save frames of stores pilfered from colonies running out of space and put them aside for just this type of situation.

A brood frame full of stores

Capped stores, if protected from mice and wasps, can be stored for some time. Open stores will usually ferment and the frames can get a bit sweaty and wet. However, if the frame is mostly capped I’m happy to offer it to a near-starving colony. A strong colony will cope with a small amount of fermented stores without any issues.

A full capped frame probably contains 2-2.5 kg of stores and this will keep the colony going until it warms up (or I next visit).

Almost every colony received a full frame of stores and I think they’ll be OK.

Interestingly, the three strongest colonies at the last visit were the exception. All these had quite a bit of nectar in the supers and so needed no additional stores. My interpretation of this is that these colonies had exceeded a population threshold above which the workforce is sufficiently large to rear new brood, defend the colony and forage far and wide collecting excess pollen and nectar.

Another example where it’s beneficial to have strong colonies.

These were the three colonies in the bee shed that were booming a fortnight ago and that remain very strong. All have clipped queens and none were making swarm preparations, so I think they’ll be OK until next week.

Famous last words.

Temperature and nectar

On retrospectively checking the weather records for my apiaries over the last fortnight it’s clear that, although temperature maxima were about normal for this time of year, the average temperatures were lower than usual.

Some days had a brief warm period, but most of the time it’s been pretty chilly.

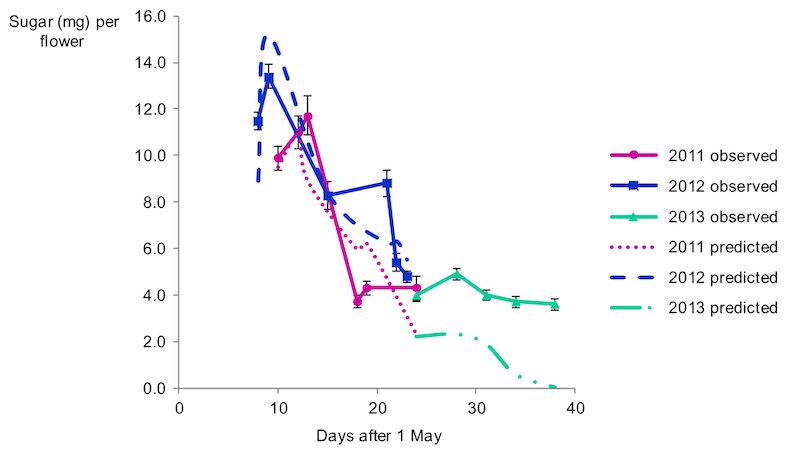

Temperature has a marked impact on the production of nectar by flowering plants. Enkegaard et al (2016) demonstrated that oil seed rape (OSR) flowering onset and both nectar production and quality are influenced by spring temperatures.

Their studies showed that the onset of flowering could be predicted by the number of growing degree days (GDD) since the start of the year. GDD are calculated by subtracting a base temperature (Tbase, in this case 0°C) from the average temperature:

(Tmax + Tmin)/2 – Tbase = GDD

They demonstrated that OSR needs 550-600 GDD for the onset of flowering.

So, of course, I did the calculations …

Using the nearest dependable weather station data I calculated that OSR flowering started on ~19th of April.

Hmmm … it can’t be that simple. If you remember this photograph from a fortnight ago (taken on 17/4/23) it shows some fields approaching full flower, and others barely started.

April 17th 2023

And, of course, it isn’t that simple.

Pierre et al., (1999) describe about 70 genotypes of group 1 winter-sown OSR where the onset of flowering varies by over three weeks in the same location. I assume, though it’s not stated, that the Enkegaard studies were based on a single genotype grown in Denmark, where the study was conducted.

Maybe the farms pictured above grow different genotypes of OSR?

Nectar quality over time

The amount of nectar produced by OSR depends upon the number of flowers each plant carries and the temperature. Low early season temperatures, for example prolonged frosts in January, February and March (henceforth ‘pre-Spring’), reduce the flower number.

Cold pre-Spring = fewer flowers

The volume of nectar produced is also temperature dependent; low temperatures (say <11°C) can reducing nectar production by two thirds from the maximum observed. However, this variation is dwarfed by the 10-fold range of nectar production per flower among the ~70 genotypes tested.

From a beekeeping point of view, a warm pre-Spring is needed to maximise flower number. If this is coupled with high-yielding strains and great foraging weather, then there’s a chance of a bonanza crop of spring honey.

But here’s a final thing to be aware of … the quality of the nectar – defined by me as sugar content, as that’s what is important to the bees – reduces during the period over which OSR flowers. This is the sugar content per flower, it does not simply reflect the reduced flower number over time (which also happens).

Nectar quality post onset of flowering

Bees make innate ‘calculations’ about the suitability of a nectar source, choosing the most profitable in the environment to forage upon. Therefore, the relative attractiveness of OSR will decrease the longer it has been flowering.

Conversely, if it’s too cold for foraging during the first week or two of flowering, the bees will miss the best nectar.

So, a cold pre-Spring followed by lower than average temperatures once the OSR flowers is likely to have a profound impact upon the productivity of your colonies … or, in this case, on my colonies 🙁 .

I’m going to dig out the climate data for the last couple of years and look for correlations with apiary honey production.

Be prepared

Of course, there’s little or nothing that you can do to change this situation. The OSR strains grown by the farmer will be determined by their seed supplier.

The weather is what it is …

However, I find it vaguely reassuring that I can at least partially understand why I’m not currently adding a fourth super to the hives, but am instead rescuing them with frames of stores to avoid starvation.

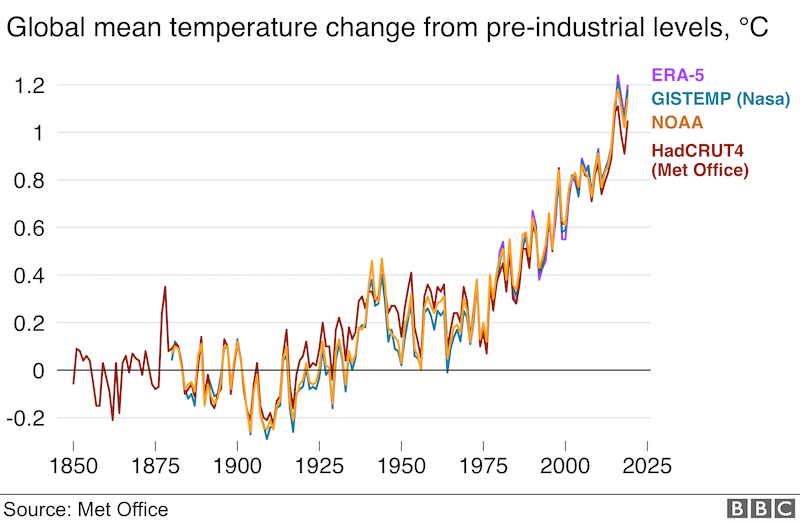

Global temperature increase since 1850

We are living on a warming planet. Global warming is not good news for honey bees (or other pollinators). There are already marked changes in the flowering times of some plants (Büntgen et al., 2022) and it’s likely that these will get increasingly ‘out of kilter’ with colony development, meaning that bees won’t be able to exploit the nectar source and pollination will be reduced.

Global warming, or more correctly climate change, will bring additional weather extremes. Some years will have unseasonably warm pre-Springs, others will have protracted frosts and markedly depressed temperatures.

And, as you can see from the work cited above, the temperature months before a particular crop flowers can influence when and how well it it produces the nectar that our bees exploit.

All we can do is be aware of the changes happening around us.

Remember that it’s not the calendar that determines what needs to be done to the colonies … be prepared to feed them when they should be collecting the nectar to feed us.

But it’s not all bad news

I had other apiaries to visit on the same trip.

In another apiary, situated further inland in a slightly warmer part of the county, with OSR flowering well just a couple of fields away, the honey supers were perhaps half full. The brood boxes were bulging with bees and brood and, although it could have been better {{6}} I was pleased with the way the season and the colonies were progressing.

I was less pleased with the fact that most of my hives were situated elsewhere 🙁 .

The second day of my trip started even colder than the first. It was 8°C when I arrived in the apiary. Fortunately I had no boxes to look through, but instead busied myself with a load of housekeeping duties in preparation for the – currently delayed – swarm season and for queen rearing (when and if it ever starts).

Around midday the cloud lifted, the temperature rose appreciably and the bees started flying in earnest.

No shortage of pollen

For an hour or so the bees worked really hard, and then – just as quickly as it had warmed up – it turned cold again and everything went quiet.

I think this type of temperature fluctuation, repeated over the last fortnight or so, with near-normal temperature maxima but lower average temperatures, is probably a significant contributory factor to the empty supers.

But let’s look on the bright side … at least they’re not swarming 😉 .

And the mention of swarming brings me back to my next little anecdote … that queen targeted by the single psychotic worker.

What happened to that queen?

If you remember, I’d returned a queen to a hive and she’d been attacked by just one worker that seemed hell bent on committing regicide {{7}}.

My final sight of the queen was her disappearing into a seam of bees with the one worker who had attacked her manically clinging to her head, abdomen curved round and probing for soft spots on the poor queen.

I feared the worst.

Somewhere in there it’s getting ugly

And was right to do so 🙁 .

I inspected the hive and found no eggs, no sign of the queen and two large queen cells. One was misshapen and partly open {{8}}, the other was sealed and – based upon the timing of the last inspection – contained a queen a day or two from emergence.

The loss of the queen was disappointing, but not the end of the world {{9}}. If I have to be queenless for a period then I’d prefer to be queenless during a good nectar flow {{10}} … with no brood to feed the workforce can keep busy collecting nectar.

Some beekeepers practice pre-emptive swarm control a week or two before a strong nectar flow starts. The old queen is removed and the colony is allowed to requeen. A really well organised beekeeper might even be able to coincide removal of the honey supers with an application of a miticide to the broodless colony if needed.

’Really well organised’ meaning a darn sight better organised than me, and with more dependable weather and nectar availability.

But I can always dream 😉 .

Rehousing a queen

One of my nucs had overwintered, but only just.

They were barely building up and the 2022 queen, although laying, was not doing so at a rate to allow the colony to expand. The queen had been laying well at the end of last season and I had hopes that she would pick up.

For reasons too complicated to recount here I had decided to move the queen alone to another apiary and make up a small nuc for her.

I popped her into a JzBz queen cage and added a few workers to keep her company.

JzBz queen introduction and shipping cage

Have you noticed that these cages come with no instructions?

I open the cage fully to add the queen (after all, she’s the most valuable part of the contents and I don’t want to risk crushing her) and then close off all but the entrance tube, which I place my forefinger over. I then pick up a few workers, one at a time, by both wings and offer them to the open entrance tube, having shaken the cage sharply to get the queen to the base.

The workers will almost always happily walk in to join the queen.

Both wings because they then cannot sting you if they’re old enough to, though it’s best to choose the youngest and fluffiest workers {{11}} to accompany Her Royal Highness. The workers will curve their abdomens round, but that will be away from your fingers, so you can be confident you won’t be stung.

Famous last words? … no, really, it’s easier than it sounds.

A revitalised queen

I’d caged the queen and popped her in my jacket pocket overnight. Queens are robust. They don’t need the TLC you lavish on queen cells. There was no need for an incubator … after all, you can send them by post.

However, by morning she was looking a little the worse for wear and the caged bees appeared a bit more sluggish than I would have liked.

They had a pea-sized chunk of fondant in the JzBz cage cap and I added a few drops of water to the outside of the cage in the morning and evening, but I didn’t get the queen into a queenless nuc (made up from two frames of emerging brood and the adhering bees) until mid-afternoon.

I left the cage cap on overnight and the following morning, just before setting off back home, checked the nuc.

An enthusiastic reception

The workers were giving the cage lots of attention, clustering tightly around it and showing no aggression. I checked the queen and she was looking great, striding around the tiny cage in a much more animated fashion than the previous day.

If I was prone to anthropomorphise {{12}} I’d suggest she was eager to get out and start egg laying.

I checked the entrance tube was still plugged with fondant and that it hadn’t set rock solid {{13}} before returning the cage to the nuc with the cap removed.

Normally, with more time available, I’d have removed the accompanying workers. Queen acceptance rates are improved if the queen is not accompanied. However, I had a fast approaching appointment, so left them ‘as is’ and expect (hope) to find her laying well next week.

Please support further articles by becoming a supporter or funding the caffeine that fuels my late night writing ...

Thank you

Bibliography

Büntgen, U., Piermattei, A., Krusic, P.J., Esper, J., Sparks, T., and Crivellaro, A. (2022) Plants in the UK flower a month earlier under recent warming. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 289: 20212456 https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2021.2456.

Enkegaard, A., Kryger, P., and Boelt, B. (2016) Determinants of nectar production in oilseed rape. Journal of Apicultural Research 55: 89–99 https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2016.1192341.

Pierre, J., Mesquida, J., Marilleau, R., Pham-Delègue, M.H., and Renard, M. (1999) Nectar secretion in winter oilseed rape, Brassica napus— quantitative and qualitative variability among 71 genotypes. Plant Breeding 118: 471–476 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1439-0523.1999.00421.x.

{{1}}: Unlikely, I know.

{{2}}: I’m not really that shape!

{{3}}: The US and UK have different meanings for this word.

{{4}}: I think?

{{5}}: Meaning ‘The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry’.

{{6}}: It could always be better!

{{7}}: If you don’t remember, here’s the original – very well read – post.

{{8}}: Odd, and no, I’ve not got an explanation for this.

{{9}}: Though it was the end of hers.

{{10}}: I’m assuming the nectar flow will appear sometime, rather than the nectar trickle we currently have.

{{11}}: Who are unable or at least less able to sting.

{{12}}: I’m not.

{{13}}: I’ve had queens trapped in these cages for a week with solidified fondant, but still released them successfully.

Join the discussion ...