The Goldilocks principle

The Goldilocks principle refers to the concept of “just the right amount” of whatever is being considered.

In this case, honey bee colonies.

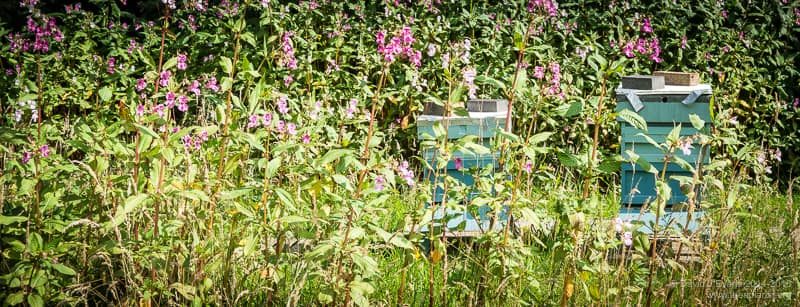

Beekeeping is a fascinating pastime. During the season – say April to September – there’s lots to keep you occupied and lots to keep your interest.

These are not always the same thing.

Weekly inspections for a start. Swarm prevention as the season properly gears up. Queen rearing. Swarms. Harvesting the early season honey. Possibly more swarms. The summer honey harvest. Autumn Varroa management. Uniting colonies and preparing colonies for winter.

It’s quieter in the winter, but there’s still lots to do. Preparation for the coming season. Bottling and selling honey. Making equipment. Scouting new out apiaries. Buying more equipment. Midwinter Varroa treatment {{1}}. Fondant top-ups for underweight colonies. Cleansing and sterilising equipment.

And all of the above needs to be done for every colony you have.

One is not enough

I’ve previously written of the importance of managing more than one colony.

The comparison is invaluable. Is the colony you’re worrying about really doing badly, or is it just that there’s a dearth of nectar and all colonies are struggling at the moment?

In addition, if there really are problems with one colony – queenlessness or bad temper for example – you can ‘rescue’ them by taking appropriate action and a frame of eggs from your other colony. Or you can unite the colonies if it’s too late in the season to rear another queen. Frankly, it’s a no brainer …

Logically, the amount of work involved in managing two colonies is double that of one colony.

Except, it isn’t.

Quite a bit of beekeeping is preparation and clearing up afterwards. For example, travelling to and from the apiary, preparing syrup, lighting the smoker, cleaning the extractor and so on. Most of these tasks take little or no more time if you’re dealing with two colonies rather than one.

The actual inspections may take twice the time, but that’s about it.

Even then, you’ll be getting twice the practice when you do inspect, so you’ll probably get more efficient, faster, with two colonies rather than one. At the risk of repeating myself, it’s a no brainer.

From too few to more than enough

Beginners often struggle in their early years of beekeeping {{2}}. Sometimes they have too few bees in the hive. The colonies are weaker than they should be to exploit the forage or to overwinter successfully. Or they lose queens during the season, suffer an extended broodless period, and need to beg or borrow a queen from elsewhere to keep the colony together. It all looked so easy in the books or in that midwinter theory course.

Except, it isn’t.

But, assuming they don’t give up, all this time they’re gaining valuable experience – week by week, month by month and year by year.

And then they pass some sort of invisible inflexion point in their beekeeping ‘career’. This is the point after which they will always have enough bees. Their colony management skills are now good enough to keep large, prolific hives. These crowded colonies necessitate careful swarm prevention and control. Colony numbers can be increased easily.

From having too few bees they can now rapidly reach the point of having too many. They learn how easy it is to make increase {{3}} using a well-timed vertical split of a vigorous, healthy colony, or by not reuniting after using the Pagden method for swarm control.

And then they learn to graft, to use mini-nucs, to overwinter 5 frame nucs and – before you know it – they’ve bought a truck 🙂

But is (many) more than two, too many?

And then, at some point, sooner or later, it can become a bit of a chore.

In my experience the swarm season and extremes of weather are the two most testing periods.

During the peak swarming period – mid/late May to mid-June here, but earlier further South – beekeeping can be a ‘full-on’ experience. Timing is critical. Miss a late open queen cell and they’ll swarm on the next available good day. You’ll run out of equipment. You’ll get phone calls in the office asking you to retrieve a swarm from a tree/swing/classroom {{4}}.

And, at the same time you’re coping with all this, it’s also the best time of the year to rear queens.

Your agenda and that of your bees is partially overlapping, but almost certainly not in sync.

And then there’s the weather … we live in a country where the weather report regularly uses the phrase ‘mainly dry’. Without specifically saying it, this means it will be wet. Almost certainly on the day you need to do your inspections, move the grafted larvae, collect a swarm and feed the mini-nucs. Too many bees and bad weather are a testing combination.

But so are too many bees and spectacularly good weather.

Beekeeping is considered a gentle and relaxing pastime. The reality, on a bright sunny day with the temperature reaching 29°C, with full honey supers to remove is rather different. It is physically demanding and exhausting work. In a beesuit and veil you will sweat buckets. Literally. I’ve had to work so hard I could pour out the sweat that had pooled in my boots.

The pain will soon be forgotten, but there will be pain.

The Goldilocks zone

But somewhere between the too few and the too many (colonies) is the sweet spot. Enough that you can experience the wonderful and fascinating variation possible in bees and beekeeping. Sufficient to engage you and allow you to experiment and try new strategies out. Enough to cope with poor seasons and still to produce some lovely honey to give to the family at Christmas and to friends at dinner parties.

This is the Goldilocks zone.

Quite where that sweet spot is will depend upon a whole host of different factors. Your interest in bees vs. other competing hobbies and pastimes {{5}}, how full-time the full-time job is, your abilities as a beekeeper and the pressure others {{6}} put on you to take holidays mid-season 😉

It might be two colonies. Not ‘just’ two, with the sort of dismissive implication that that’s not what being a real beekeeper is. There are some outstanding beekeepers I know who have a couple of colonies in a good area for forage and who consistently produce spectacular honey yields per colony. They are excellent observers, skilled practitioners and really understand what’s happening in their colonies at all times of the season.

Or it might be 200 … in which case you’ve got a stronger back and a bigger truck than me 🙂

For me it’s about a dozen. I can produce enough honey to sell or give away and still have sufficient colonies to dabble or experiment with. Not ‘experiment’ as in my day job (I have more hives for that), but to investigate different ways of improving my stock, alternative approaches to queen rearing and introduction, other types of mite control etc.

Not all these experiments work. Some are an unmitigated disaster, others are no better than the way I previously did whatever ‘it’ was.

Have you used a Taranov board? Me neither. But I’d like to this season.

Space and spares

The Goldilocks principle can also be applied to having ‘just the right amount’ of equipment and space to manage your chosen number of colonies. This includes, but isn’t restricted to, apiaries, brood boxes, supers, split boards, crownboards, stands, clearers, hive tools, more supers, dummy boards, roofs, frames, more frames, yet more frames etc.

I’ve never met a beekeeper who has managed to achieve this 😉

Colophon

Look who is sleeping in my bed!

The Goldilocks principle is named after the well-known 19th Century fairy tale “Goldilocks and the Three Bears“ in which Goldilocks, a little girl, always chooses the ‘just right’ option – of bed, porridge, chair etc. when lost in the forest and finding a house owned by three bears. In each case the ‘just right’ option is the one in the middle e.g. the bowl of porridge that was not too hot, or too cold, but was just right. Goldilocks, the little girl, was introduced in a variant of the original tale “The Story of the Three Bears” in place of a cantankerous, foul-mouthed old woman. Perhaps unsurprisingly, she was preferred by the target audience 😉

The Goldilocks zone has a specific meaning in astronomy where it indicates the habitable zone around a star. This is defined as the range of orbits within which liquid water could occur if there is sufficient atmospheric pressure.

{{1}}: If you’re reading this in mid-February and haven’t yet treated your colonies with dribbled or vaporised oxalic acid then it’s probably too late to do this effectively. Your colonies should have a reasonable level of brood in them now … upon which all those untreated Varroa are already munching.

{{2}}: Which is why mentoring is so important … it speeds up the learning process and it gives the beginner confidence.

{{3}}: This is the term used by beekeepers to indicate an increase in colony or hive numbers … it’s always seemed to me a rather quaint or old-fashioned phrase.

{{4}}: It may well not even be a swarm from your hives, but that’s a subtlety that you may be unable to explain over the phone … or that you actually have a full-time day job, are currently 250 miles away and aren’t available until 9pm.

{{5}}: Golf? Really? Despite working in the ancestral home of golf I increasingly agree with the sentiment expressed by H.L. Wilson that “Golf has too much walking to be a good game, and just enough game to spoil a good walk”.

{{6}}: The unenlightened … have they no idea that May and June are the best time of the year to rear queens?

Join the discussion ...