Triumphs and tragedies

Synopsis: Having dealt with beekeeping tragedies last week, it’s now time to consider landmark events (‘triumphs’) in beekeeping. These four things – successful overwintering, swarm control, finding the queen and queen rearing – are what I consider the most notable. All beekeepers should be able to achieve these, and their beekeeping will benefit as a consequence.

Introduction

In the second part of the highs and lows of my (or an average beekeepers’s {{1}} ) beekeeping career I discuss what I consider are the four most significant events in the progression from total beginner to my current level {{2}}.

These highs and lows, or ‘triumphs and tragedies’, stemmed from a question posed during a live-streamed Q&A session with Lawrence Edwards from Black Mountain Honey. I didn’t think I answered it particularly well then – though some of the things below were definitely included – so have had another crack at it.

The tragedies I covered last week – the loss of a queen, a swarm or a colony – aren’t really tragedies. As I said in the introduction then, ” … the observant and well-prepared beekeeper can avoid most of the ‘tragedies’, and recover from almost all of them”.

However, unlike the tragedies that really aren’t tragedies, these triumphs really are landmark events that significantly improve your beekeeping.

Unsurprisingly, some of the triumphs I discuss below are how you recover from – or avoid altogether – the tragedies I mentioned last week.

Successful overwintering

Studies from Tom Seeley (in his book The Lives of Bees) indicate that a swarm from a wild-living colony has about a 23% chance of surviving the winter. Swarms perish for a number of reasons; many starve to death, others die from pathogens {{3}}, a few queens likely fail and some colonies are lost due to ‘natural disasters’ such as lightning strikes or storms or bears.

Although I don’t know the percentage breakdown of these causes of death, I’d be surprised if the combination of queen failures and ‘natural disasters’ account for more than a small percentage.

In contrast, I expect that starvation and disease account for most losses of ‘wild’ colonies.

The survival rate of managed colonies is not entirely clear as it differs with the group or individual being surveyed.

The relatively small-scale annual BBKA surveys suggest that about 80% (the average of the last 12 years) of colonies overwinter successfully. The much larger Bee Informed Partnership (now defunct) surveys {{4}} report a slightly lower figure of 70%.

Finally, the COLOSS surveys – covering Europe and a few other countries {{5}} – helpfully split winter losses into those due to ‘mortality’ (presumably disease and starvation) from queen failure and natural disasters, and usually report survival rates of 70-80% {{6}}.

COLOSS reports losses due to queen failure and natural disasters are typically about 5-7%.

Let’s assume for the sake of argument that these are unavoidable, and that they’re as likely to befall a managed hive as a ‘wild’ colony.

Averages, outliers and being ‘better than average’

These losses, when analysed statistically, show considerable variation between individual beekeepers. Some never lose colonies during the winter, others often experience high rates of colony mortality.

When I last checked {{7}} all my colonies have survived this winter. My average losses over the last decade (about 200 ‘colony winters’) are well below 10%. Many of the experienced beekeepers I know routinely experience losses in the 5-10% range.

In contrast, inexperienced – and sometimes longstanding {{8}} – beekeepers may lose many or even all the colonies they ‘manage’. Many give up, others make up the losses through splitting, swarms or purchases, and soldier on to the next winter, only to experience the same disappointment again {{9}}.

Some losses are expected – though perhaps no more than the ‘unavoidable’ 5-7% due to ‘natural disasters’ and queen failures.

However, the remaining 90-95% of colonies should survive, particularly if we assume that their loss would be due to starvation or disease … both of which squarely fall under the term ‘management’ when considering managed colonies.

This management is the responsibility of the beekeeper – s/he must ensure that the mite (and consequently virus) levels are minimised at the right times during the season, and that the colony has sufficient stores to overwinter successfully.

Take your winter losses in autumn

The final point to remember is that the successful management of colonies involves excluding those from going into the winter that are likely to fail.

Weak colonies in late autumn, or early autumn queen failures, are often doomed anyway.

Don’t let them become a (BBKA, BIP or COLOSS) statistic.

If healthy, unite these colonies with strong colonies and then plan for some additional splits the following season to make up the ‘on paper’ loss. Far better you strengthen another colony than condemn a weak colony, or one with a poorly mated queen, to a lingering death in midwinter.

I therefore consider the first landmark event (‘triumph’) in beekeeping is the successful overwintering of the majority (over 90%) of the colonies managed – irrespective of the severity or duration of the winter.

Achieving this involves a combination of skills:

- successful disease management (which I term ‘Rational Varroa Control’)

- appropriate feeding in the autumn

- the ability to judge colonies unlikely to survive before it’s too late to unite them

- well-sited apiaries unlikely to flood or be hit by falling trees (or visited by rampaging bears)

- provision of young and well-mated queens to head colonies

A strong and healthy colony is likely to overwinter successfully. It’s also more likely to build up strongly the following spring, and therefore will probably swarm … or at least try to.

Which neatly takes me to the second of the ‘triumphs’ that a beekeeper should aim to achieve.

Successful swarm control

Swarm control is the management of a colony that has started making queen cells, and is therefore likely committed to swarm within a few days.

It is a necessity if (or when!) swarm prevention stops working.

I visited one of my apiaries last week. There were a dozen colonies in the apiary last year and I know I missed one swarm.

‘Missed’, but not ‘lost’.

I’d found the bivouacked swarm, dropped it into a nuc box and successfully re-hived them 🙂

However, while taking some willow cuttings I discovered wax deposits on another of the small trees I’d planted.

Clearly a swarm had bivouacked here for a day or so and I’d both missed and lost it 🙁

For the last couple of seasons, while living remotely, I’ve usually been very pro-active in my swarm control.

If a few colonies in the apiary start building queen cells I use the nucleus method of swarm control and take the queens out of all the strong colonies and then allow them to requeen.

For swarm control the nucleus method is almost foolproof.

It is very successful in preventing the loss of a prime swarm (one with the mated queen). However, with really strong colonies, there remains the risk that more than one virgin queen emerges. I suspect I’d missed a queen cell and lost a cast headed by a virgin queen. I know that all my colonies requeened successfully and without unexpected delays.

So, this was an example of unsuccessful swarm control, but it was less of a problem than the loss of a prime swarm (as I still had the mated queen tucked away in a nuc somewhere).

Timing and mechanics

Successful swarm control involves the ability to recognise when a colony is actively making swarm preparations i.e. being able to find queen cells, and then knowing exactly what to do (and when to do it) to prevent the colony from swarming.

The first is observational and will improve the more hives you inspect (or should if ‘seeing’ is coupled with ‘understanding’).

The second – ‘what and when’ – is the mechanics of swarm control:

- find and isolate the mated queen somehow (Pagden or vertical split, nucleus etc.) in a way that ensures her survival. Her continued availability is important if the original colony does not successfully requeen.

- find all the queen cells and leave sufficient to ensure the colony can requeen but not so many that the colony generates casts. I usually leave a single charged queen cell (but clearly left more than one in the colony that swarmed onto that willow above).

- the ability to judge that the colony has successfully requeened and that the new queen is well mated, so guaranteeing the survival of the colony.

There are dozens of different swarm control methods. Most share some common features in terms of actions and timing.

However, that doesn’t mean that you can ‘mix and match’.

- Learn one method.

- Know when to apply it. Understand its pros and cons.

- Have the equipment to hand during the ‘swarm season’.

- Analyse what went wrong if it doesn’t work.

Achieve all this and you will be successful at swarm control, your colonies will be stronger during the peak nectar flows of the season, you’ll collect more honey and they will overwinter more successfully.

Swarm control – knowing what to do when, and employing it successfully – moves you from hit and hope scrabbling around with “Finger’s crossed they won’t swarm” to a reassuring {{10}} “What will I do with the additional colony?”

It’s a real confidence builder … and while we’re on the topic of confidence.

Finding the queen … quickly, and every time

Watch a new beekeeper look for the queen. They will sequentially and thoroughly inspect every frame in the colony. Each frame is turned and rotated slowly as taught in the winter ’Start beekeeping’ courses. They’re often particularly careful to check the sidebars and the bottom bar of the frames. The underside of the queen excluder (QE) is carefully scrutinised.

A gentle puff of smoke every couple of frames keeps the colony nicely subdued.

Fifteen minutes later they find her, on a frame of stores. The frame had already been inspected at least once 🙁

In contrast, an experienced – and good (!) – beekeeper gently lifts the QE, checks it briefly and closely observes the density of bees along the visible seams. She then uses a small amount of smoke to allow the dummy board and outer frame to be removed. These are carefully placed aside.

The beekeeper then splits the remaining frames where the density of young bees is the greatest, opening a 2 cm gap. The nearer frame facing the gap is then carefully removed and the queen will usually be found on it, or on the far side of the other frame facing the gap.

It’s all over in 90 seconds and – to the inexperienced – it looks like magic.

It’s not.

It’s also not 100% guaranteed, but it happens enough that it’s certainly not chance.

Of course, you don’t need to find the queen to be reasonably certain the colony is queenright.

Usually their behaviour, the presence of eggs and the absence of sealed queen cells is a sufficiently good indication that there’s a queen present.

Gently does it

But, when you do need to find her – for example, to employ one of those swarm control methods that requires the isolation of the queen {{11}} – the 13.5 minutes saved by the good beekeeper really helps avoid frustration (and agitated bees).

In the example above the beginner found the queen on a frame of stores, almost certainly because he disturbed the colony using too much smoke and by slowly going through the box frame by frame. The queen was ‘chased’ across the box, scuttled across the floor or around the sidewall of the hive and ended up on the outer frame of stores or pollen.

The experienced beekeeper used almost no smoke. The bees barely knew she was there. She split the frames where there were more young bees. These will be tending the queen and the young larvae. If the queen wasn’t on the face of the first frame checked she’s likely to be on the reverse of the facing frame (having moved there to avoid the light streaming in through the gap between the frames).

You can keep bees without being able to find the queen, but certain things are much easier if you can reliably and quickly locate her.

This is a skill that some never acquire and that others seem to naturally possess.

But it can also be learned.

It’s easier to do with a calm and gentle colony.

However, it’s perhaps learned fastest with a double brooded box of suicidal psychotics 😉

And, if you’re good at finding the queen you will be asked {{12}} to requeen one of those double brooded boxes of suicidal psychotics.

Which is why this third landmark event in your beekeeping is inextricably linked to my final choice … the ability to actively rear high quality queens.

Queen rearing

Of all the things I’ve learned since starting beekeeping – including the huge number of things I’ve subsequently forgotten – queen rearing has been, without doubt, the most useful.

I’m talking here about ‘active’ queen rearing, rather than passively allowing a queenless colony to generate queen cells and requeen itself.

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with this ‘passive’ approach. I use it every year. However, it doesn’t teach you as much about beekeeping.

I consider the following are the direct and indirect benefits of active queen rearing. These justify inclusion of queen rearing in this list of landmark events in beekeeping:

- to be successful you need the ability to judge the quality of the bees over the course of the season. There’s no point in rearing queens from poor quality stock.

- rearing good quality queens means you can readily improve the quality of your colonies, simply by requeening them. You should see the benefits in 2-3 years (or months in the case of some colonies I’ve requeened 😉 ).

- queen rearing means you need to acquire the skills and confidence to find and (often) handle the queen. Marking and clipping the queen makes your beekeeping easier.

- you can readily achieve sustainability in your beekeeping. No need to buy in queens or nucs. No need to rely upon capturing swarms to maintain colony numbers.

- you can have spare queens and nucs available when you need them, or generate surplus for gift/sale.

- young queens – which you ensure by requeening – head stronger colonies, are less likely to swarm and overwinter better.

- queen rearing requires understanding the colony manipulations needed to start queen cell production. This necessitates good observation and skilled beekeeping.

And there are probably as many again that I could include if I hadn’t already written 500 words more than I’d intended 😉

The most fun you can have with a beesuit on?

However, almost as importantly … “of all the things I’ve learned since starting beekeeping – including the huge number of things I’ve subsequently forgotten – queen rearing has been, without doubt, the most” … enjoyable.

Perhaps not ‘the most fun you can have with a beesuit on’ {{13}} but pretty darned close.

Actually, I’ve already thought of a few more things that should be in the list above:

- the skill to prepare nucs for queen mating (either mini-nucs or 2-5 frame nucs). And subsequently manage them.

- an ability to have nucs available for overwintering to make up losses or for (profitable) sale early the following season.

- the confidence to dabble with methods for colony preparation to find strategies that suit your own bees and the local environment.

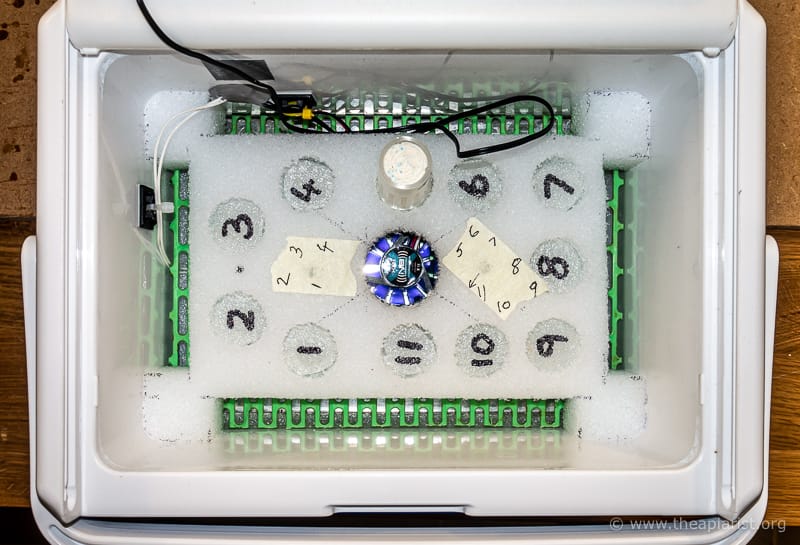

- out-of-season projects to entertain you (like building my wildly over-engineered queen cell incubator) during the interminable dark winter months.

- etc.

Only a relatively small percentage of beekeepers actively rear queens.

I suspect many are dissuaded because they think it requires skills they don’t have, and are unlikely to acquire without years of practice.

Au contraire as a Gilles Fert, a well-known French queen rearer, would say.

You may not (yet) have the skills but few of them are ‘mission critical’ and most can be learned relatively easily.

Of the four things discussed in this post, queen rearing is the skill that has provided the greatest benefit to my beekeeping.

And enjoyment.

Go forth and multiply 🙂

{{1}}: Which is pretty much what I am.

{{2}}: Of ‘mid-table mediocrity’ as a football pundit would say.

{{3}}: Primarily Varroa and DWV.

{{4}}: Accounting for about 10% of all managed colonies in the USA.

{{5}}: A total of about half a million hives.

{{6}}: Be warned … there are some significant issues with the sampling methods used for all these surveys. None appear rigorously ‘ground truthed’.

{{7}}: And at the risk of tempting fate …

{{8}}: They are ‘experienced’, but only in the sense of keeping bees for a long time.

{{9}}: And, if it’s not a disappointment, it probably should be … it certainly is for the bees.

{{10}}: And not in the slightest bit arrogant.

{{11}}: But remember there are also methods that do not require the queen to be found.

{{12}}: Because they couldn’t possibly be your bees.

{{13}}: At least that can be discussed before the watershed.

Join the discussion ...