Waiting

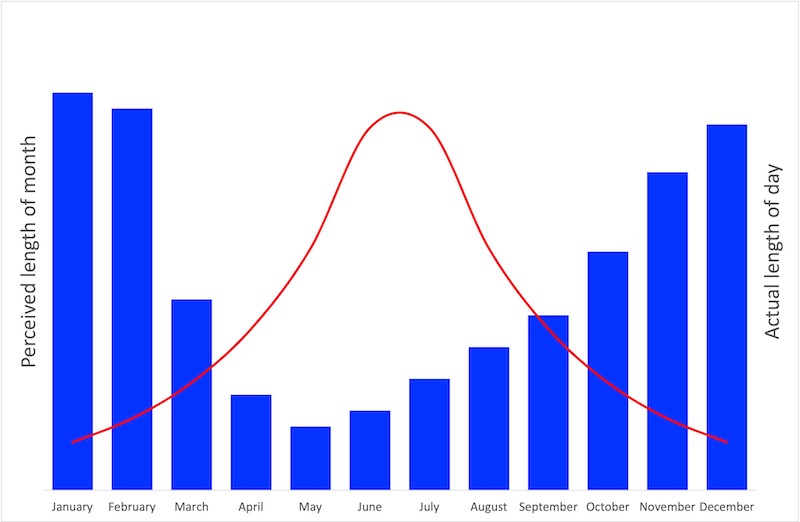

Beekeepers will be familiar with the strange distortion of time that occurs during the season. The months with the shortest days appear to drag on interminably. In contrast, the long days of summer whizz by in a flurry of activity {{1}}.

This is due to the indirect influence of latitude on our bees.

In winter, they’re largely inactive … and so are we, and time drags.

In summer, they’re busy foraging and breeding and reproducing (swarming) and foraging more and robbing … and we’re running around like headless chickens {{2}} trying to keep up.

Not always successfully 🙁

Latitude

The UK is a small country. The distance between the extremities – Jersey {{3}} and the Shetlands (both islands, some distance from the mainland {{4}} ) – is only about 800 miles, or a bit less than the long diagonal across California.

Nevertheless, this has a profound effect on daylength and temperature … and therefore on the bees.

On the winter solstice the day length in Jersey is about 8 hr 11 min. On the Shetlands it’s less than 5 hr 50 min. But that is reversed by the summer solstice. The longest day on the Shetlands is over 2.5 hours longer than the 16 hr 14 min that the poor crepuscular folk in Jersey enjoy {{5}}.

For convenience, let’s assume that bees need an average maximum temperature of 10°C to fly freely {{6}}. That being the case, bees in St Helier, Jersey, might fly for 9 months of the year, whereas those in Lerwick, Shetland, fly for less than 6 months of the year {{7}}.

Think back to those headless chickens. All of that “foraging and breeding and reproducing (swarming) and foraging more and robbing“ is being squeezed into about one third less time in Lerwick than in St Helier.

The winters are not fundamentally different. But the transition to spring happens much earlier in the south.

All of which makes this time of the year hard going for those of us living at northern latitudes … which, in a roundabout way, was what I was pondering while I stared at a depressingly inactive entrance to one of my colonies a fortnight or so ago.

Ignore Twitter

For a few days Twitter had been littered with short videos of bees piling into hive entrances laden with pollen.

Helpful comments like “Girls are very busy today” or “15°C today and all colonies flying well” accompanied the videos.

I was ankle deep in snow and we’d recently had overnight temperatures below -14°C.

Bees from one of my colonies on the west coast had been out on cleansing flights {{8}} but the other was suspiciously quiet.

Obviously it was quiet when there was snow on the ground, but this situation continued as the weather warmed and the snow disappeared.

Despite a reasonable amount of experience in keeping bees in Scotland, and an awareness that the Twitter posts might have been from a beekeeper in St Helier, I was starting to get concerned about this second colony {{9}}.

I knew there were live bees in the box as it has a clear crownboard. I could remove the roof and block of insulation and see the bees. However, the bees appeared to still be clustered and, having added a tray under the open mesh floor, there was little evidence of brood emerging.

In contrast, the other colony was flying well, collecting pollen and the cluster was largely dispersed.

Worrying times.

Fretting

Perhaps they’ve gone queenless?

Do queenless colonies tend not to break cluster as early in the season?

Do they not have any need to collect pollen because there’s no brood to be reared?

That’s scuppered my queen rearing plans for the season ahead … is it too late to order a couple more nucs?

Is it too early in the season to unite them and at least use the surviving bees?

Should I have a quick look in the centre of the cluster?

Should I wait until tomorrow when the weather is looking a little better? {{10}}

Waiting

This went on for the better part of a week. The weather was not great, but was steadily improving. I was working outside much of the day.

The flying colony continued to fly. There was ample evidence they were rearing brood.

The non-flying colony just sat there and sulked 🙁

And then, on the penultimate day of February, out they came …

The day was no warmer than the preceding one, it was certainly no sunnier. If anything it was actually a bit worse.

But the bees came out as though someone had uncorked a bottle 🙂

First a couple around midday, then a dozen or two by 1pm and finally reaching a few hundred by 2pm (just after the picture above was taken {{11}} ).

Almost all the flying bees appeared to be taking orientation flights. Only a very few were collecting pollen.

And from that point on it’s been a case of ‘normal service is resumed’.

The colonies have continued to fly on the good less bad days. Both colonies are busy with the gorse pollen. Both – by the look of the trays under the OMF {{12}} – are rearing reasonable amounts of brood.

Why the sulking?

Both my west coast colonies were obtained from the same source, though I know the queens are from different lineages. I suspect the fact that one was flying well before the other simply reflects differences in their genetics.

It’s notable that after the first day or two of strong flying activity, both colonies have quietened down significantly. The proportion of bees taking orientation flights compared with foragers has decreased significantly.

I interpret that burst of flying activity as a mix of new bees taking their first flights and older bees reorienting after a long period confined to the hive.

I’m no longer worried that the queen failed in midwinter 🙂

Patience, young grasshopper

This trivial example is just one of many where the beekeeper has to wait for the bees.

You can’t rush them.

They will go at their own pace and, usually (or possibly even, almost always) it will work out OK.

I was concerned about that apparently inactive colony. Had I intervened I would have done more harm than good.

Since there was little I could do that would constructively help the situation I simply had to wait.

Which made me think about other examples where waiting is usually the best policy in beekeeping.

Queen rearing

I’ve given a couple of talks recently on queen rearing and am already well-advanced with my own plans for the season.

Queen rearing involves several key events, all of which must more or less coincide. The colony (and other colonies in the region) must have sexually mature drones present. There really needs to be a good nectar flow to ensure the developing queens are well nourished. Finally, the weather must be suitable for queen mating.

Again, you can’t rush these things. You might have no influence on them at all …

The swarm in the skep (above) was captured on the last day of April 2019. It was an unusually early spring in Scotland and the earliest swarm I’ve seen since 2015.

The bees had judged that conditions were right. There were reasonable numbers of drones about and the weather remained pretty good for at least the first half of May. The swarm was a prime swarm, and I fully expect that the virgin queen that emerged in the originating colony got successfully mated {{13}}.

In contrast, three years earlier the conditions at the end of April are shown above. Colonies contained few drones and swarming first occurred in late May.

Under these conditions, starting queen rearing is a pointless exercise. The colonies aren’t ready, the environment is hostile and there is probably insufficient nectar being collected.

It pays to wait.

Queen mating

Anyone who has kept bees for a year or two will be familiar with the often interminable wait while a virgin queen gets mated.

Assuming a colony swarms on the day that the developing queen cell(s) is capped {{14}}, the queen that follows her must emerge, mature, go on her mating flight(s) and then start laying.

My calculations are that this takes an absolute minimum of 14 days.

For the first seven days the new queen is pupating, she then emerges and matures for 5-6 days before going on one (or more) mating flights. After mating it then takes a further 2-3 days before she starts laying.

I’ve not looked through my records but cannot remember it ever taking 14 days. In reality, even with ideal conditions, at least 17-18 days is more usual and 21 days is not at all uncommon.

It’s worth remembering that there’s a time window within which the queen must mate. This opens 5-6 days after emergence (when she becomes sexually mature) and closes at 26-33 days after emergence, after which time she’s too old to dependably mate well.

A variety of factors can influence the speed with which the queen gets mated.

Bad weather is the most obvious. If the weather is poor (rain, cool, very windy etc.) she won’t venture forth. For Scottish beekeepers, there’s a nice study by Gavin Ramsay {{15}} of the total number of ‘good’ queen mating days we enjoy in our brief summers … it can be very few indeed.

Queens mate faster from smaller hives. Queens in mini-nucs mate faster than those in 5-frame nucs which, in turn, mate faster than those in full hives.

And, as far as the beekeeper is concerned, these few days drag by very slowly {{16}}.

There’s nothing to be gained by checking and re-checking. There’s potentially a lot to be lost if you get in the way of a queen returning from a mating flight.

Just wait … and more often than not it will all be just fine.

Enthusiastic beginners

The final example where there’s a benefit from waiting is for the beginner beekeeper getting their very first colony {{17}}.

They’ve attended a winter ‘Introduction to beekeeping’ course, they’ve read and re-read the Thorne’s catalogue (and ordered loads of stuff they don’t need) and they are desperate to start keeping bees.

I know the feeling, I was exactly the same when I started.

Every year I get requests for nucs in March, or “as soon as possible” or “so I can install them in the hive at Easter”.

The commercial suppliers offer bees early in the season, often from April onwards.

Or did, before the ban on imports, though some still do.

But in my opinion I think there are real benefits from waiting until a little later in the season.

In the absence of imported packages or nucs, there are only two sources of nuc colonies early in the season:

- Overwintered nucs. These are usually in very short supply and therefore command a significant price premium. The queen will be from the previous year … not in itself a major problem, though they are probably more likely to swarm than a nuc headed by a current year queen.

- Bees in a box headed by a queen that was imported. The proportion of bees in the box related to the queen depends upon the time that has elapsed since the queen was added to the box. Think about the timing of brood development … it takes three weeks from adding the queen to have any adult bees related to her. It takes six weeks or more to re-populate the box.

I think the price premium of an overwintered nuc is justified because they have already successfully overwintered. However, a similar box of bees would be perhaps half the price two months later {{18}}.

It’s an expensive way to start if things go wrong.

What could possibly go wrong?

An overwintered nuc will probably build up very fast, perhaps outstripping the skills (or confidence) of the tyro beekeeper.

If the weather is bad the new beekeeper potentially has a large, poorly-tempered, colony to manage. It’s daunting enough for some beginners doing their first few inspections, but if they’re struggling with a fast-expanding colony – potentially already making swarm preparations – on cool or wet days, then it can become a bit of a chore.

Or worse.

A few stings, a bee or two in the veil and the beekeeper gets a bad fright. The next inspection is missed or delayed. The colony inevitably swarms as the weather picks up.

Suddenly 75% of their £300 investment has disappeared over the fence {{19}} and they’re left with a hive full of queen cells.

In contrast, the beginner who starts with a nuc later in the season, headed by a ‘this years’ queen, avoids all those problems.

The new queen is pumping out the pheromones and there’s very little chance the colony will swarm. They’ve arrived in late May or early June, the weather is perfect and the bees are wonderfully calm.

They still build up at quite a pace, surprising the beginner. They’ve drawn out all the comb in a full brood box within a fortnight and will need a super just about in time for the summer nectar flow.

Beginners often open their colonies too frequently. They dabble, they fuss, they make little tweaks and adjustments.

Sometimes – like I did with my first colony – they inadvertently crush the queen during a particularly cack handed colony inspection.

D’oh!

It’s still early in the season so mated queens are difficult to get. Pinching a frame of young brood from another colony weakens it at a critical time in its build up, and leaves the beekeeper reliant on excellent weather to get a new queen mated {{20}}.

Altogether not ideal.

So beginners should wait. By all means attend the apiary sessions or tag along with an experienced beekeeper during April and May. You’ll learn a lot.

The wait will do you and, indirectly, the bees good.

At the very least it’s great preparation for the waiting you’ll do for queens to get mated, or for a colonies to start flying well next spring 😉

{{1}}: The graph is drawn for northern latitudes … readers in Australia and New Zealand will be familiar with the effect, though the line will have a trough in the middle where the bars will be tallest.

{{2}}: An idiom that dates back to at least 1570 but that didn’t apply to Mike, the headless chicken.

{{3}}: Please note the ‘boringly pedantic’ correction made Ron Hayes in the comments about Jersey being a Crown Dependency. Thanks Ron.

{{4}}: On the mainland, Land’s End to John o’ Groats, as the bee flies, is 600 miles.

{{5}}: All data from https://www.timeanddate.com/

{{6}}: Please note that this is a rough approximation that makes my life easier, rather than a scientifically accurate guide to the thermodynamics of honey bee flight. In reality they’ll often fly on days when the temperature reaches high single figures (Centigrade), particularly if the sun is shining on the hive entrance. And, yes, I know that thermodynamics isn’t the right word to use in this context.

{{7}}: Data for St Helier and Lerwick.

{{8}}: A very genteel way to describe what the trip is actually for.

{{9}}: I’ve only currently got a couple of colonies on the west coast, the rest are remaining in Fife. All of my east coast bees had been flying earlier in the month.

{{10}}: And the correct answers to those 7 questions are: Don’t know, don’t know, don’t know, don’t know, probably, no and yes. In that order.

{{11}}: I’m enthusiastic about bees, but not so fanatical that I’ll sit and watch them for 2 hours on a February afternoon … the hive is just a few metres from my door.

{{12}}: Normally I’d term these Varroa trays, but these colonies are Varroa-free so it’s not an appropriate term. I leave the tray in for 24-72 hours and monitor the appearance of wax cappings that fall through the OMF.

{{13}}: It wasn’t my colony that had swarmed … it never is :-)

{{14}}: A reasonable assumption, though it’s not invariable.

{{15}}: Review into options for restocking honey bee colonies in Scotland, The Scottish Government, 2016 (PDF).

{{16}}: Despite the fact they occur during the months which ‘appear’ to be the shortest in the year – another example of ‘beekeeping timewarp’.

{{17}}: Or, ideally, colonies … as it’s always better to start with two.

{{18}}: And should be available from a local beekeeper.

{{19}}: Up to 75% of the flying workers in the colony leave with the prime swarm.

{{20}}: I got my first bees in late May, inadvertently did away with the queen and cadged a frame of eggs in mid-June … when there was ample to spare.

Join the discussion ...