Weed and feed

Weed and feed is a generic term that describes the treatment of lawns to simultaneously eradicate certain weeds and strengthen the turf.

It seemed an appropriate title for a post on eradicating mites from colonies and feeding the bees up in preparation for the winter ahead.

Arguably these are the two most important activities of the beekeeping year.

Done properly they ensure you’ll still be a beekeeper next year.

Ignored, or done too little and too late, you’ll join the unacceptably large number of beekeepers who lose their colonies during the winter.

They think it’s all over

In Fife, on the east coast of Scotland, my beekeeping season effectively finishes with the midsummer ‘mixed floral’ nectar sources. This is a real mix of lime, blackberry, clover and Heinz nectars {{1}} … many of which remain to be identified.

There’s no reliable late nectar flow from himalayan balsam around my apiaries are and not enough rosebay willowherb (fireweed) to be worthwhile, though in a good year the bees continue to collect a bit from both into early September.

But by then the honey supers are off and extracted. Anything the bees find after that they’re welcome to.

The contrast with the west of Scotland is very marked. Over there my bees are still out collecting reasonable amounts of late heather nectar, though the peak of the flow is over.

Storing supers

Once the honey supers are extracted they can be returned to the colonies for the bees to clean up prior to storing them overwinter. However, this involves additional trips to the apiary and usually necessitates using the clearer boards again to leave them bee-free before storage.

I used to do this and quite enjoyed the late evening trips back to the apiary with stacks of honey-scented supers. More recently I’ve stopped bothering and instead now store the supers ‘wet’. The main reasons for this are:

lazinesslack of time- unless you’re careful it can encourage robbing, by wasps or bees. You need to return supers to all the colonies in the apiary and if you have the hives open too long it can induce a frenzy of robbing {{2}}

- the honey-scented supers encourage the bees to move up faster when they’re used the following season

If you do store the supers ‘wet’ make sure the stacked boxes are bee and wasp-tight. Mine go in a shed with a spare roof on the top. If there are any gaps the wasps, bees or ants will find them and it then becomes very messy.

I know many beekeepers who wrap their supers in clingfilm. Not the 30 cm wide roll you use in the kitchen but the sort of metre wide swathe they used to wrap suitcases in at London Heathrow.

Dated super frames

The drawn super comb is a really valuable resource and can be used again and again, year after year. I usually record the year a frame was built on the top bar. Many are now over a decade old and have probably accommodated at least 80 lb of honey in their lifetime {{3}}.

The timing of late season Varroa management

During the brood rearing season the Varroa levels in the colony will have been rising inexorably. Without intervention the mites will continue to replicate on developing pupae that would otherwise emerge as the all-important overwintering bees. These are critical to get the colony through to the following spring.

When Varroa feeds on a developing pupa it transmits the viruses – primarily deformed wing virus – it acquired from the last bee is fed on. These viruses amplify by about a million-fold within 24-48 hours. Pupae that do not die before eclosion may have developmental defects. Importantly, those that appear normal have a reduced lifespan.

The overwintering bees should live for months, but might only live for weeks if their virus levels are high.

And if enough overwintering bees have high viral loads and die prematurely, the probability is the the colony will perish in the winter.

You therefore need to reduce mite levels before the overwintering bees are exposed to Varroa.

The full details and justification are in a previous post logically entitled When to treat?

TL;DR {{4}} … late August to early September is the best time to treat to protect the winter bees from the worst of the ravages of mite-transmitted DWV.

Use an appropriate treatment

You need to reduce the mite levels in the colony by at least 90% to protect the winter bees.

To achieve this you need an appropriate miticide used properly.

I use Apivar.

Apivar is an Amitraz-containing miticide. Although there are reports of mite resistance in some commercial apiaries, the pattern is very localised (individual hives within an apiary, which is difficult to understand) and in my view it is currently the best choice.

What are the alternates?

- MAQS – active ingredient formic acid – poorly tolerated at high temperatures, but can be used with the supers present

- Apiguard – active ingredient thymol – ineffective at lower temperatures (it needs an ambient temperature of 15°C to work – that’s not going to happen in Scotland in September).

- Apistan – active ingredient a synthetic pyrethroid – unsuitable as there is widespread resistance in the mite population.

Using Apivar

Apivar treatment is temperature-independent. It cannot be used when the honey supers are present. You simply hang two strips in the hive for 6 to 10 weeks and let them do their work. The bees tolerate it well and, unlike MAQS or Apiguard, I’ve not seen any detrimental effects on the queen who continues to lay … making more of those important winter bees.

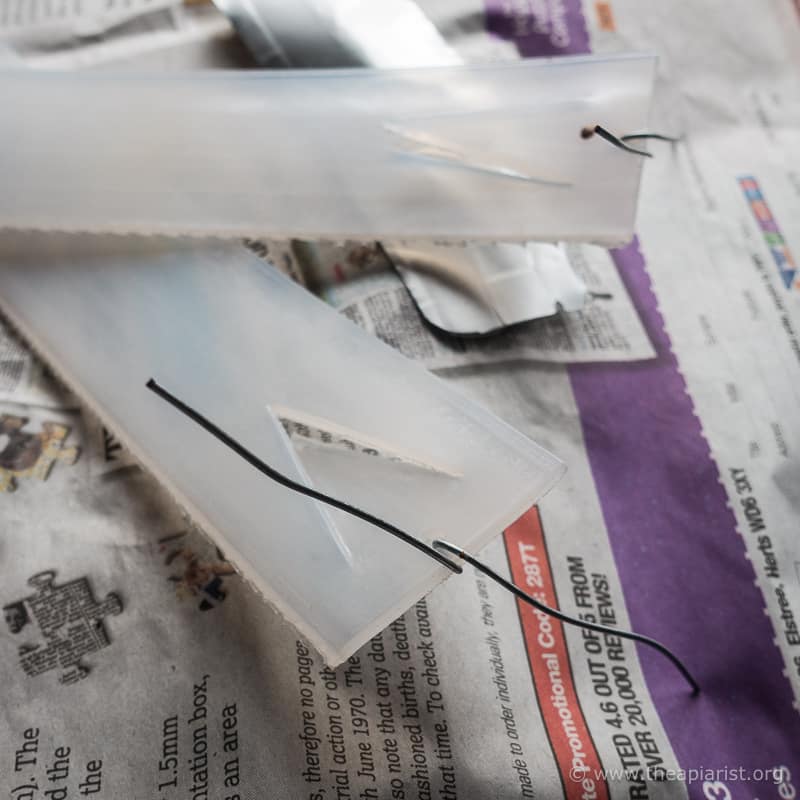

Each strip consists of an amitraz-impregnated piece of plastic tape with a V-shaped tab that can be pushed into the comb to hold it in place.

This generally works well as the frames are usually not moved much as there’s no need for inspections this late in the season.

However, the strips can be a little fiddly to remove (or fall off during frame handling) and some of our research colonies will continue to be used for at least another month. I’ve therefore used a short piece of bent wire to hang the strips from in these hives.

I place the strips in opposite corners of the hive, set two frames in from the sides.

Apivar, wax and honey contamination

Although Amitraz is not wax soluble {{5}} there are recent reports on BEE-L that one of its breakdown products are, including one that has some residual miticide activity {{6}}.

I therefore try and get all the bees into the brood box before starting treatment (I described nadiring supers with unripe honey last week).

Very rarely I’ll leave the bees with a super of their own unripe honey. Usually this happens when the brood box is already packed with stores and overflowing with bees. In this case I’ll mark the super and melt down the comb next season rather than risking tainting the honey I produce.

I attended a Q&A session by the Scottish Beekeeping Association last month in which the chief bee inspector discussed finding Apivar strips in honey production hives. He described the testing of honey for evidence of miticide contamination and potential subsequent confiscation.

This is clearly something to be avoided.

Remember to record the batch number of Apivar used and note the date in your hive records. I just photograph the packet for convenience. The date is important as the strips must be removed after 6 weeks and before 10 weeks have elapsed.

It’s finally worth noting that the instructions recommend scraping the strip with a hive tool part way through the period if they are being used for the full ten week course of treatment. The strips usually get propolised into the frame and the scraping ‘reactivates’ them to ensure that the largest possible number of mites are killed off.

And, after all, that’s what they’re being used for.

Apivar is expensive

Well … yes and no.

Yes it feels expensive when walking out of Thorne’s of Newburgh clutching one small foil packet and being £31 poorer.

But think about it … that packet is sufficient to treat 5 colonies.

Is £6.20 too much to spend on a colony?

My 340 g jars of honey cost more than £6.20 and my productive colonies produce at least one hundred times that amount of honey.

I don’t think 1% of the honey value is too much to spend on protecting the colony from mites and the viruses they carry.

Mite drop

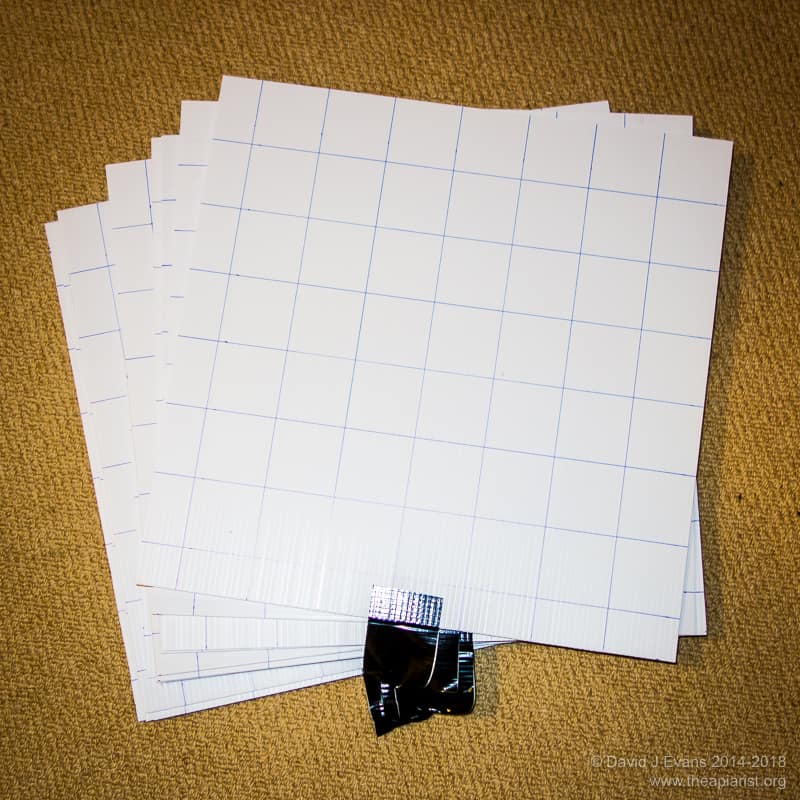

Varroa killed by the miticide {{7}} fall to the bottom of the hive. If you have an open mesh floor (OMF) they fall through … onto the ground or the intervening neatly divided Varroa tray, enabling you to easily count them.

Remember that amitraz, the active ingredient of Apivar, works by direct contact. This is why you place the strips diametrically opposite one another so that as many bees as possible contact them. Unlike Apiguard, it makes no difference whether the Varroa tray is present or not.

It is useful to ‘count the corpses’ to get an idea of the infestation level and the efficacy of the treatment.

I’m going to discuss what you might expect in terms of mite drop in the winter (I need to plot some graphs first). However, this is something you could think about before then … knowing Apivar kills mites in less than three hours after exposure, what do you think the mite drop should look like over the 6-10 weeks of treatment?

Enough weeding, what about feeding?

I treat and feed colonies on the same day.

I also do the final hive inspection of the season. At this I look for evidence of a laying queen, the general health of the colony, the amount of brood present and the level of stores in the brood box.

If the colony is queenless (how did that happen without me noticing earlier?) I simply unite the colony with a strong, healthy queenright colony. I don’t bother testing it with a frame of eggs … time is of the essence.

It’s too late to get a queen mated (at least in Fife … when I lived in the Midlands I got a few September queen matings but they could not be relied upon) and I rarely, if ever, buy queens.

I only feed with fondant in the autumn.

Convenience food

I described fondant last week as a convenience food.

I’ve described in detail many of the benefits of fondant in numerous previous posts. Essentially these can be distilled to the following simple points:

- zero preparation; no syrup spillages in the kitchen, no marital strife.

- bucket- and feeder-free; no need to carry large volumes of syrup to the apiary and no feeders to store for the remaining 11 months of the year. All you need to feed fondant is a queen excluder and an empty super … and you’ve got those already.

- easy to store; unopened it keeps for several years {{8}}.

- super speedy; I can feed a colony, including cutting the block in half, in less than 2 minutes.

- good for queen and colony; perhaps that’s stretching it a bit. What I mean is that the bees take the fondant down more slowly than syrup, consequently the queen continues to lay uninterrupted as the brood nest does not get backfilled with stores. This is good for the colony as it means the production of more winter bees.

- an anti-theft device; you can’t spill fondant so there is much less chance of encouraging robbing by neighbouring bees or wasps.

- useful boxes; the empty boxes are a good size to store or deliver jarred honey in – each will accommodate sixteen 1 lb rounds.

I’ve fed nothing but fondant for about a decade and can see no downsides to its use.

Money, money, money

I’ve never used anything other than commercially purchased “baker’s” fondant … don’t believe the rubbish (about ‘additives’) some of the bee equipment suppliers use to justify their elevated prices.

You should be paying about £1/kg … any more and you’re being robbed. This year (2020) I paid less than 90p/kg.

Do not use the icing fondant sold by supermarkets for Christmas cakes. I’m sure there’s nothing much wrong with it, but – at £2/kg – you’ll soon go bankrupt.

Tips for feeding fondant

Fondant blocks are easier to slice in half if they are slightly warm.

Use a sharp bread knife and don’t slice your fingers off.

You can cut the blocks in half in advance in the warmth of your kitchen and then cover the cut faces with clingfilm to prevent them reannealing, but I just do it in the apiary.

Alternatively, use a clean spade {{9}}.

Always place the block cut face down on a queen excluder directly over the top bars of the brood frames. With a full block, it’s like opening a book and laying it face down. Do not place it above a crownboard with a hole in it.

You want the bees to have unfettered access to the open face of the fondant block.

Ideally, use a framed wire queen excluder.

These are easier to lift off should you need to go into the colony.

Which you don’t 😉

There’s no need to continue inspections this late into the season. Go and enjoy a week or two away in Portugal … or perhaps not 🙁

If you need to store an unused half block of fondant wrap the cut face in clingfilm.

All my colonies get one full block (12.5 kg) and many get a further half block, depending upon my judgement of the level of the stores in the hive.

Insulation

The bees will take the fondant down over 2 – 4 weeks. They do store it, rather than just using it as needed. By late September or early October all that will remain is the blue plastic husk. The photo below is from mid-October. This colony has had a ‘topup’ additional half block after already storing a full block of fondant.

With cooler days and colder nights, you want to reduce heat loss by the colony and minimise the dead space above the bees into which the heat escapes.

Although bees take fondant down at lower temperatures than they do syrup, there’s no point in giving the colony more additional space to heat than they need.

Depending upon the availability of equipment I do one or a combination of the following:

- use a poly super to provide space for the fondant

- compress the fondant (use your boot) into as little space as possible and you squeeze it into a 50 mm deep eke, which (conveniently) is the same depth as the rim on my insulated polcarbonate/perspex crownboards {{10}}.

- use an eke and an inverted perspex crownboard with no need to compress the fondant

- add a 50 mm thick block of insulation above the crownboard, under the roof (which may also be insulated)

Fondant block under inverted perspex crownboard – insulation block to be added on top is standing at the side

Oh yes … before I forget … completely ignore any advice you might read on using matchsticks to provide ventilation to the hive {{11}}.

They think it’s all over … it is now

That’s the end of the practical beekeeping for the season 🙁

If your colonies are strong and healthy, if the mite levels are low and they have sufficient stores, there’s almost nothing to do now until March {{12}}.

Now really is a good time for a beekeeper to take a holiday.

Make a note in your diary on the date you need to remove the Apivar strips

Write up your notes, pour a large glass of Shiraz and make plans for next season 🙂

{{1}}: 57 varieties!

{{2}}: One good reason to do this in the evening.

{{3}}: I know many beekeepers who have much older – and perfectly usable – super frames. Look after them well and save the bees the time and energy spent in redrawing comb each year.

{{4}}: The internet acronym for too long, didn’t read … but perhaps you should. It is one of the most-read pages on this site and one of the most important posts I think I’ve written. Many beekeepers treat mites far too late in the season to protect the winter bees. The UK has some of the highest overwintering colony losses in Europe. Are these facts related?

{{5}}: Unlike Apistan … most tested commercial foundation is contaminated with pyrethroids.

{{6}}: I’ll discuss this in more detail sometime in the future – I’m already running out of space.

{{7}}: We’ll ignore the fact that technically they’re paralysed, not killed outright. Paralysis doesn’t do them much good though …

{{8}}: I buy a few hundred kilograms at once and so always have some available when needed.

{{9}}: In the apiary … see the reference to marital strife above.

{{10}}: Wow! … a post from 2013.

{{11}}: Actually, that matchsticks post is not dissimilar to a draft post I have written on the use of fondant for winter feeding. Historically it’s only used for a winter top up. Why? Beekeeping is deeply conservative (with a small ‘c’), possibly because it is often taught by beekeepers who themselves were trained millenia ago. It’s also riddled with myths. My draft of “101 Beekeeping myths” is now onto volume three … and I’ve only reached the letter H of the alphabet. Think about what’s best for the bees and learn from observing them … I’ll return to this sometime in the winter, so should stop ranting now.

{{12}}: But don’t forget the importance of treating the colony when broodless in midwinter … the mites that escape treatment in the autumn will continue to reproduce and, if not treated in winter, you’ll be building up problems in the future.

Join the discussion ...