Your second season

Synopsis: In your second season of beekeeping use swarm control to create an additional colony. It will improve your beekeeping and provide insurance against calamities. Make plans now and buy equipment in the sales.

Introduction

Going by the sound of the wind and the rain outside, the beekeeping season is now well and truly over. Entirely appropriately, as it was the autumn equinox on Saturday, the first of the equinoctial gales (Storm Agnes) is currently battering the west coast and I didn’t see a single bee when I checked the hives earlier.

It’s too soon to review the season but, with the National Honey Show approaching and end-of-season {{1}} sales from some suppliers, it’s not too soon to think about equipment needs for next year.

If 2023 was your first season then I hope it was successful … you’re allowed to define success using broad and generous criteria.

Do you still have the colony you started with? Did you manage to get any honey? Have you started feeding them and treating them to control Varroa?

If you can answer yes to those three questions then it was probably successful.

If you answered no to the last question then you need to get a move on to ensure that you have bees at the start of next season.

And, to be frank, it’s only if your bees are doing well at the start of next season that you can properly conclude that this season was a success. Getting the colony to the autumn is like being three under for the first nine holes of a round of golf … it can still all go horribly wrong {{2}}.

And, if it was your first season and it was successful, then it’s not too soon to be thinking about what you might expect next year as there will be some new challenges and opportunities.

Years of experience

I know almost nothing about the readership of this site, other than those that regularly comment or who have made contact about talks.

My web server records where the page is accessed from, the browser used and whether the user is on a laptop, desktop or phone. However, the stuff that is really important in terms of understanding bees i.e. the years of beekeeping experience (‘hive years’), remains an unknown.

It’s therefore difficult to know how to pitch articles; all the basics with no assumed knowledge risks losing the experienced reader, whereas hardcore stuff on the science of bee behaviour or rearing queens from eggs will inevitably disenfranchise beginners.

And if I cater for both audiences the posts will become (even more) ridiculously long.

So, my assumption is that the readership reflects the cross-sections of beekeepers I meet or give evening talks to.

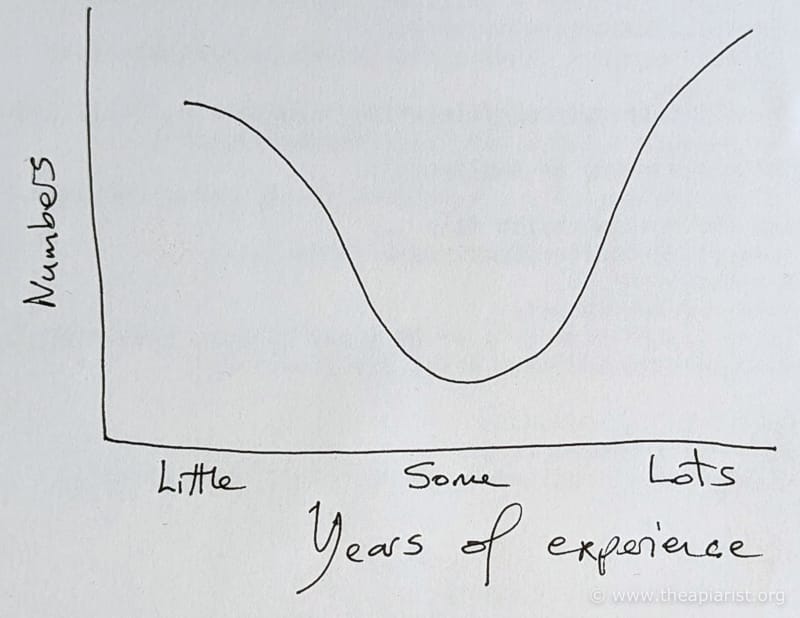

In terms of years of experience {{3}} a significant proportion only have one or two years experience, a smaller number have a handful of years, and rather more have accumulated a decade (or decades) of experience.

I think this reflects that a lot of people who start beekeeping give up after a season or two. Their colony dies overwinter, or swarms, they lose confidence (or never gain it in the first place), get distracted or find it too difficult i.e. they have an unsuccessful first season.

Partly this is because – done properly – beekeeping is quite difficult.

Sure, the fundamentals are straightforward, but this assumes good observational and interpretative skills. It’s an intensely practical pastime and you cannot learn it from books, or do things to a carefully choreographed calendar.

Tricky when you take latitude, altitude and different years into account.

The same but different … your second season

Every season is different. Some years are warmer than others, some are so wet you’re feeding the bees for months at a time, some start late and end early leaving you feeling like you blinked and missed it.

One of my winter talks is on preparing for the season ahead. It covers (inevitably briefly) spring expansion, swarming, queen rearing, the honey harvest, feeding and treating. In it I make the point that the timing (or even occurrence) of some of these events depends upon geography, climate and the vagaries of the particular season.

But there are a couple of thing that are likely to be new in your second season, irrespective of the geography, climate or whether it’s a cold, wet, dry, hot or whatever type of year.

The first of these is that you’ll have a chance to observe the early spring build up of the colony. After a long winter it feels great to be opening hives again and scrabbling through the frames to see what’s happening.

Don’t.

At least, don’t do it too early. You’ll learn almost nothing and you’ll disturb the colony unnecessarily. Just let them get on with things. If they’re bringing in pollen on good flying days then all should be well.

What’s too early? It all depends upon where you are and the weather … here (Scotland) it’s sometimes early/mid May, with an unusually warm Spring or further south it might be 4-6 weeks earlier.

Swarming

The second major difference is that you will almost certainly have to deal with swarming.

Most beginners start with a nuc obtained in late Spring, or perhaps an early June swarm collected by an association member. That being the case it’s unlikely either will have swarmed in your first season.

The nuc was probably headed by a new queen, preferably homegrown, or imported from somewhere exotic like Italy or Malta. Being a current year queen her pheromone levels will be high and the colony should not have swarmed.

A captured swarm (at least a prime swarm) will have been headed by a queen from the previous year, but it’s unlikely to have the time to build up strongly enough to swarm again.

Remember, the bees don’t read the books … I’m talking about “usually” here. Some will inevitably swarm in your first season.

But, assuming you started with a new nuc or swarm, you can be almost certain they will try and swarm in your second season.

One, two or three?

One of the best ways to gain beekeeping experience is to inspect more hives. If you’ve only got one colony you might only do ~12-15 inspections a year {{4}}.

When you do those inspections how do you know things are all OK or whether they’re going horribly wrong?

Are there no eggs because there’s a nectar dearth and the queen has stopped laying?

Alternatively has the queen stopped laying because you made her the filling in a ‘Hoffman-sandwich’ last week, crushing her between the side bars as you returned frames to the box?

By far the easiest way to determine this {{5}} and more difficult scenarios is by comparison.

If two colonies sharing an apiary are both egg-free it’s more likely to be a nectar dearth rather than clumsiness.

For several years I’ve considered the most important thing a new beekeeper can do in their second season is to get a second colony.

It’s not only the comparisons that are useful. If you do squash the queen and then – in a panic – massacre all the resulting queen cells {{6}} you still have the opportunity to rescue the situation by transferring a frame of eggs/larvae from your second colony.

Late in the season, should one colony be terminally queenless, you can unite the colonies and still be a beekeeper the following spring.

Increasingly however I think three colonies is the optimal number. Partly this is based upon psychology; there’s a reluctance to use the last of something {{7}} and uniting leaves you with a singleton. Something for a future post.

In sync with your bees

So, as you enter your second season you should be thinking of getting a second colony.

You should also be expecting that the first colony you are currently overwintering is likely to swarm.

How convenient … both you and your bees are in sync and want to expand.

In future years, assuming you continue to accumulate experience and insight and understanding – you’ll be looking at ways of reducing, or at least not increasing, your colony numbers. But in your second season you are in the happy situation that both you and the bees have, or should have, similar goals.

But that doesn’t mean that there’s nothing to do until next May when swarm preparations will be underway.

In fact, these preparations should probably start in the next few weeks with the end-of-season sales. There’s also some additional preparations to be made during the first or second inspection of the season.

In my view the simplest way to make increase in a controlled and managed way is to use the nucleus method of swarm control, either reactively or proactively.

Timed correctly, this barely impacts honey production.

Done properly, it’s 100% effective at preventing swarming.

I’ve discussed the nucleus method of swarm control previously and you should re-read that post for further details. The comments below are really about the preparation needed and applying it proactively i.e. before the colony starts to make swarm preparations.

The nucleus options

A nucleus hive – at least as far as this post is concerned – is a hive that takes full-sized frames, just less of them.

Less usually means 5 or 6. There’s no precise definition and I’ve also got ‘nuc boxes’ that take 2 or 8 frames. For the purpose of this post let’s stick with 5 or 6.

The box takes fewer frames and is therefore narrower than a 10 or 11 frame hive. Other than that it consists of all the bits you might expect; a floor, brood box, crownboard and roof.

They can be built from all sorts of things including Correx, polystyrene (poly) or cedar. My advice would be to only consider poly nucs. Cedar are lovely, but expensive and poorly insulated. Correx are too thin for anything but really good weather.

For swarm control and making increase i.e. for housing small colonies in the summer it probably doesn’t matter what the nuc is made from, but for overwintering (which you should want to do in the future) then poly is the only game in town.

I own or have used about 5 different makes of poly nucs. Most are Thorne’s Everynucs, but I’ve bought some from Maisemore’s in the last few seasons.

My advice would be to buy the thickest poly nuc which has a separate floor and brood box. This offers the best insulation {{8}} and the most flexibility for things you might want to do in the future.

The thicker the better

If the suppliers advertise the poly thickness {{9}} they often base it on the thickest part of the box.

‘Quack, quack, oops’ … what’s important is the thinnest part as this determines how well insulated the box is. There’s little point in having 60 mm end walls, if the large recessed handhold regions are only 20 mm thick, or the roof is ‘wafer thin’.

Ask around your association. See what other beekeepers are using. Have a good nosey at what’s on offer at the National Honey Show. Visit the suppliers. A poly nuc will cost you £50-75 and should last you 30+ years.

It’s an investment, so invest wisely.

My choice, of those I’ve used, would be:

- Maisemore’s poly nuc, the version with a separate floor and brood box

- Thorne’s Everynuc

- (A very distant third choice) Maisemore’s poly nuc with the integrated floor and brood box

- Anything else

I discuss some of this in more detail, including the measured wall thicknesses on the nucs I have, in a recent post on overwintering nucleus colonies.

And, once you’ve bought one, protect your investment by painting it properly. Two coats of Hammerite Garage Door Paint will provide protection against the elements (UV and rain). It also makes them look rather smart {{10}}.

And, while you’re spending your hard-earned money, buy a compatible eke (if you feed fondant) or syrup feeder. Some clever designs do both. Don’t assume they’ll be available next year … it’s not unusual for designs to be improved change.

That’s the first bit of the preparations over. Have a good Christmas!

Stores

A nucleus of bees is just a small colony. As such, it should be relatively self-sufficient, at least if the weather and the environment are benign. However, if conditions are adverse it might struggle; to expand it needs to rear new brood which takes workers to nurture the developing larvae (‘it takes bees to make bees’) and more workers to forage for the protein and carbohydrate they need.

Since bees can’t be in two places at once it’s important that the nuc is provided with sufficient stores.

Which brings me to those first couple of inspections of the season.

If you fed your colony well the previous autumn it’s likely they will have an outer frame of sealed stores still largely untouched when you inspect in the spring. If they don’t then it’s likely your bees are prolific Italian types, or you didn’t feed them enough, or both.

Once the bees are flying well and the season has properly started (e.g. there is fresh nectar being collected) they can spare these stores. Think of it as conveniently prepackaged stores for the nuc you’ll be making in a month or so.

Remove the frame of sealed stores and replace it with a frame of foundation. I would normally insert the foundation between an outer pollen-filled frame and the edge of the broodnest; this allows the bees to expand the broodnest once the new frame has been drawn.

Keep that frame of sealed stores in a bee-, wasp- and mouse-proof location … your previously painted new nuc box with the entrance closed is as good as any.

Splits or swarm control? It’s just semantics

The simplest way to get the timing right for the preparation of your nuc is to wait for the colony to produce queen cells. It’s at this time that the colony is strong enough and the weather likely to be best suited to get the new queen mated.

That’s what I recommend you do … probably in mid/late May, depending upon your latitude and altitude.

The bees determine the timing of events and are less likely to get it wrong than you are. They’ve had a few million years of evolution to optimise things, you’ve done 19 inspections and had bees for less than a year.

Full instructions are in my previous post on the nucleus method of swarm control.

Alternatively, you can do it proactively.

You don’t wait for queen cells, but you split off a 2-3 frame nuc from the colony. The nuc contains the queen and frames of emerging brood. They build up into a new colony.

The original colony is now queenless, it raises some emergency queen cells. Six or seven days after making the nuc you go through the de-queened hive, removing all but one well-formed queen cell.

A month later (or less in a good year, but let’s not be ambitious) you have a newly mated queen heading your hive, and a rapidly expanding nuc.

Is this swarm control or a split?

It’s actually both {{11}}.

Timed properly, the original colony should not swarm. It also has minimal impact on honey production. In the pandemic year I did this with all my colonies in Fife, lost no swarms and achieved an excellent honey crop.

Timed properly

The reason I recommend – at least in your second season – that you wait until queen cells are produced is that this is more likely to ensure a successful outcome.

Timing is critical.

Applied too early and the nuc struggles to build up as it’s not warm enough or there’s insufficient forage available. At the same time the original hive may not requeen promptly if conditions for queen mating are borderline.

There’s lots to go wrong if you start too early.

Alternatively, applied too late, you may find queen cells appear in both the nuc and the original hive. I interpret this as the colony being already intent on swarming but that I intervened too late and made the nuc up too strong. This situation is rescuable, but it’s perhaps not ideal in your second season.

In due course the nuc will need a full-sized hive (so buy one of those in the sales as well). You may not get a honey crop from it in your second year – though it’s not out of the question – and the ageing queen might be replaced by supersedure late in the season, or will overwinter and probably try and swarm in your third season.

But by then you’ll know exactly what to do and when to do it.

Note

Don’t be tempted to split 2-3 frames off your hive without the queen. A small split like that is unlikely to produce good quality queen cells (or queens). Make a small queenright nuc and let the remainder of the hive – perhaps 7-8 or more frames of brood – rear the new queen.

{{1}}: Told you so!

{{2}}: Solheim and Ryder Cup reference … I’m nothing if not topical!

{{3}}: Which I’ll acknowledge isn’t always the same as knowledge or understanding.

{{4}}: Assuming one per week during the swarm season and less frequently at other times.

{{5}}: Which is easy to work out anyway.

{{6}}: Been there, done that, got the T-shirt.

{{7}}: Think Rolos.

{{8}}: Assuming the poly has similar insulation properties, which I’m not qualified to judge … and the suppliers don’t publish.

{{9}}: And they usually don’t.

{{10}}: Do this ASAP … don’t leave it until a day before you need it. ‘Do as I say, not as I do’.

{{11}}: Or it’s semantics and doesn’t matter what you call it.

Join the discussion ...