2024 in retrospect

I predict that the beekeepers who enthusiastically read this site during late May are now busily preoccupied by other things as we gallop towards Christmas and the end of the calendar year.

Other than me, you might be the only person who reads this ... have you no last-minute Christmas shopping to do? Perhaps you've done it already?

Whatever, this seasonal preoccupation is the only explanation I can think of for the absence of any feedback this time last year when - for the first time since 2014 - I failed to produce a '[this year] in retrospect' post.

Instead - Bah! Humbug! - I wrote about things that annoy me ... not very seasonal at all.

For better or worse, sometime around mid-December, I've usually written something about the season receding in the rearview mirror. It's usually drafted shortly after I finish the last of my practical beekeeping for the year - the administration of the winter oxalic acid dribble. Or, this year, vaporisation as the weather was warm, and the bees were, at best, loosely clustered {{1}}.

Like the view in the mirror, the retrospective view of the year can be a little distorted, with the more distant events difficult to make out, while those just passed are still fresh and sharp. So, as an aide memoir I usually have a peak at my beekeeping records, together with the Met Office for help on the amount and type of rain weather we 'enjoyed' at various times of the year.

That distorted view also means that some of the most glaring errors, the queens I 'fumbled' like an England fielder in the slips, the clearer added upside-down, the dropped frames and the 'bee up the leg of my shorts' incident can be conveniently forgotten.

All valuable learning experiences, of course 😉.

So, how was it for you me?

Overall, I'd say it was a reasonably satisfactory season.

A few things went very well indeed. In fact, so well I can't really work out what it was I didn't do that allowed them to be so successful {{2}}. Most of these things had to do with honey ...

Some things went less well, but were still a long way from being awful. My queen rearing was one of these, though these 'successes' were negated by very poor queen mating results; rearing the queens is only halfway to having mated queens, and these proved frustratingly elusive. I blame the weather, but that's what all beekeepers do, so it's a bit of a cop-out. Having looked back at the weather records I think it was a combination of weather and my timing and/or availability, overlaid with a generous dose of bad luck.

My competence (aka ineptitude) had very little to do with it.

For once.

Did anything go really badly (other than queen mating)?

Probably not. I've ended the season with many fewer colonies than I started, but that was deliberate and due to uniting them, rather than losing them. My swarm control was not perfect, though I only know of one swarm I definitely lost ... it loitered at the top of a very tall cypress tree for a day or two, studiously ignoring my bait hive, then disappeared for pastures new {{3}}. This loss was balanced by a swarm (not mine) arriving in a bait hive, so my final "contamination of the environment with unwanted swarms" score is a respectable zero for the season.

So, let's look at a few of these events with the benefit of hindsight. What could I have done to mitigate the failures, and what should I do again (or not do again) to recapitulate the successes?

Honey

Unusually, my first task of the season was honey extraction. Specifically, it was the extraction of the 2023 heather honey from my bees on the remote West Coast. Due to a variety of reasons - more honey than I was willing to 'crush and drain', Covid, indolence, wrong equipment etc. - I didn't get round to this until early January.

A little context here. My bees on the West Coast occupied a stunningly beautiful, but barren and wet, environment in which any honey was a bonus.

In the five years I had bees there, only one produced a reasonable surplus, and it wasn't unusual to be feeding colonies in May.

And June.

And July {{4}}.

Not always, but frequently enough that the four full(ish) supers I got in 2023 were a very pleasant surprise, as well as being unusually valuable on account of their rarity {{5}}.

Four supers is not a lot of honey, but it's too much (in my opinion ... you might be a sucker for punishment) to 'crush and drain' the honey from the comb.

'Crush and drain' (or is it strain?) is an achingly slow, dull, messy and repetitive activity that always seems to leave a distressing large amount of honey trapped in the comb, rather than in the bucket below the sieve.

The alternative methods appeared to be a 'loosener' to make the thixotropic honey easier to extract in a conventional radial or tangential extractor, or a fruit press to manually force the honey out of the comb. For reasons discussed at the time, neither of these approaches particularly appealed ... looseners are not inexpensive (and usually involve handling one frame at a time) and the fruit presses I considered were almost universally viewed as suboptimal for beekeeping.

Squeeze and release

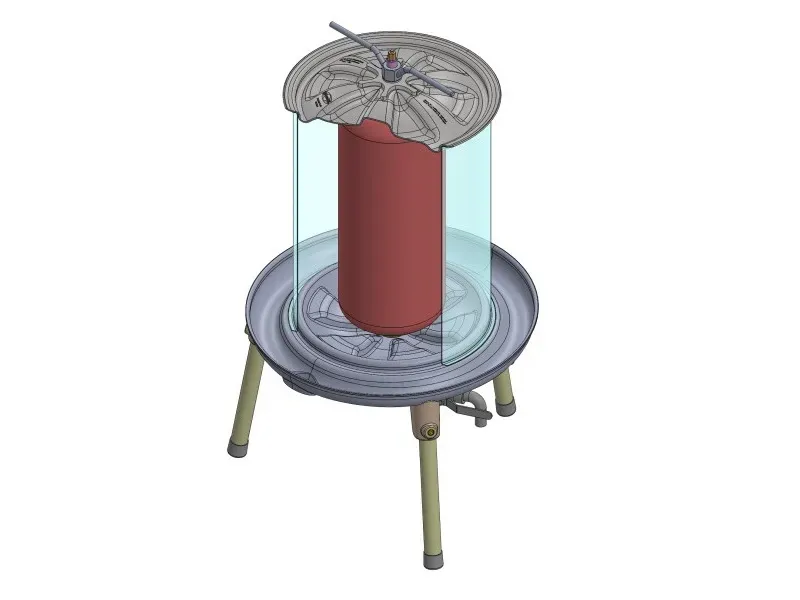

Fortunately, social media and regular reader Elaine came to my rescue and recommended a Speidel Hydropress. This is a fruit press, consisting of a perforated drum with a central 'bladder' that inflates when filled - under pressure - by water.

The Speidel Hydropress (photos 1 and 2 from Speidel)

It's a fantastic bit of equipment, beautifully constructed out of thick (and heavy) food-grade stainless steel. The 'control panel' underneath consists of a pressure gauge and adjustable inlet/outlet valves.

The only thing I was missing was the 'pressure' bit.

Our water supply was a burn 1 km up the hill and a very long hosepipe. Although there was usually ample water in the burn, the hosepipe and the water tanks at the top of our land ensured that the water pressure remained well below 1 bar, far too low to drive the hydropress {{6}}.

I rigged up a WiFi-controlled 3 bar water pump fed by a dustbin full of water, all connected with yet more hosepipe.

Why WiFi?

I was already apprehensive about using large volumes of water under high pressure. It would be fine to wash the car, or jet-wash the decking, but indoors, in proximity to the only heather honey I'd produced in four years?

Tempting fate, too risky.

I located the pump and reservoir just outside the backdoor of my extraction room, attached to an extension lead, with hosepipes snaking across the floor connecting the inlet and outlets of the hydropress.

All very Heath Robinson, but remarkably effective. I could turn the pump on and off as needed using my phone, and therefore carefully regulate the pressure exerted by the water-filled bladder on the honey.

"Alexa, turn on the water pump."

I managed to get through the entire harvest with no spillages, of water or honey ... and I only tripped over the hosepipe once.

That's what I call a miracle success 😄.

Although a little fraught at the time - as I'd not done it before - the extraction was both straightforward and efficient.

Break-even beekeeping

The Speidel hydropress is a relatively expensive piece of kit, costing a bit less than a hobbyist 9-frame electric extractor {{7}}. However, in a single run I extracted 40 kg of wonderful heather honey. It was very easy to use and did a very good job of extracting the honey, leaving me with a reassuringly dry 'crust' of compressed wax.

By the time I'd taken into account the water pump, waders, hosepipe and additional fittings needed, I'd spent about £1000 ... by coincidence, almost exactly what the heather honey eventually sold for over the following few months.

However, I'd reasoned that I needed to speculate to accumulate ... investment in the hydropress would pay dividends in future years, and the heather harvest couldn't always be as hit-and-miss, could it?

Well, as far as the West Coast goes, I'll never know 😔.

Well before all the honey was sold, we'd decided to move to the Scottish Borders. We have some heather here, though there's not a lot in the Cheviots which are distantly visible from my office window. I need to explore a bit more. In the meantime, the hydropress is wrapped up safely at the back of my storage container and the water pump will be sold as we have high-pressure water here ... literally 'on tap'.

The Speidel hydropress is an excellent piece of kit. It's a little more tricky to use than an extractor, and a bit more difficult to clean (so might not be ideal as an Association purchase, though this depends upon how fastidious your members are and/or how fierce your secretary is). The comb is destroyed during extraction, but the efficiency of extraction is almost certainly better than using a loosener/extractor combination {{8}}. I don't know about the longevity of the bladder, but replacements are available.

And, there's always the opportunity to make cider ... 🍻.

More honey

Moving into the new house coincided with the summer honey harvest. Other than the availability of a large van to transport the supers, this combination has absolutely nothing to recommend it 😞.

Over a four-day period I collected ~30 cleared supers from my Fife apiaries, drove them across to our - now largely empty - house on the West coast, fixed a broken extractor and then extracted over 280 kg of summer honey. This was from just 9 production colonies, with the best generating almost 40 kg.

For me, my bees, and my part of Scotland, that's a pretty good harvest.

I was pleased ... and tired.

I was also surprised.

Not at the final extracted weight; I'd already carried the full supers from the hives to the van, and then from the van to a stack in the extracting room, and then from the stack to the extractor ... I was achingly familiar with the weight.

What surprised me was that the bees had managed to collect that much nectar in the first place, considering the rather poor weather that masqueraded as 'summer' this year.

My recent and repeated struggles to get queens successfully mated was still fresh in my mind. I'd put this down to 'the weather', which had been underwhelming, at best. I assumed that the rubbish conditions that had kept the virgin queens at home, or that had not allowed them to go on sufficient mating flights (see below) would also have curtailed a lot of foraging activity.

Obviously not.

Or perhaps it did, and I would have got half a ton if the weather had been better?

Together with the Spring honey crop, largely oil seed rape gathered in a rush during the last 7-10 days of flowering, which was about average, it's been a good year for honey.

It was also very different to 2023. In that season I'd had a record Spring crop but nothing in the summer.

Since my customers tend to favour the clear, runny, 'zingy', summer honey, and because this honey takes less effort to prepare and jar (no endless stirring to prepare a good 'melt in your mouth' soft-set) I'm a 'happy camper' {{9}}.

So much more than honey

That's part of the subheading {{10}} for this site, because there's a lot more to beekeeping than honey production.

Whilst I probably started beekeeping because of the attraction of making a few jars of honey, it's not the aspect of the hobby that I most enjoy.

Honey is good because it makes great Christmas presents, it pays for the miticides and the frames and foundation (and hydropresses), but - let's be honest - there's a lot of drudgery, and a good deal of hard work, in producing lots of honey. There's the heavy lifting, the extracting, the jarring, and the endless cleaning up afterwards.

Instead, I get the most satisfaction from rearing queens and improving the quality of my bees (or trying to). It's an all-encompassing activity, involving record keeping and colony selection throughout the year, colony management and preparation, grafting day-old larvae (the method I choose to use, but there are numerous other methods) and then patiently waiting while the virgin queens return from their orientation and nuptial flights.

Although it's a season-long passion, the real work occurs between May and July, and during that period this year I was more than a little preoccupied with two things:

- preparing to move house, an activity which included 'rationalising' huge, teetering stacks of beekeeping equipment secreted in and behind sheds and garages, in various out apiaries and spare rooms, together with all the other essentials I seem to have acquired (22 boxes of nitrile gloves, 60 - yes, 60 - unused circular polystyrene vent covers for Abelo crownboards, several strange 'experimental' brood boxes, and lots of mini-nucs etc.). Where did it all come from, and more to the point, where was it all going?

- singularly failing to coordinate my beekeeping with the gaps between repeated periods of very poor weather.

Anomalies

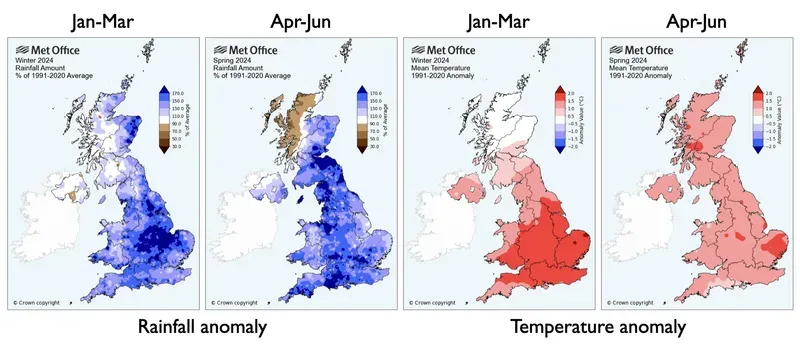

Although the headline figures - 130 mm of rain in May, minimum/maximum temperatures of -3°C and 19°C etc. - give an indication of what the weather was like, it's often more informative to look at the current season in comparison with the average conditions that prevailed during the same period in a number of previous years.

Whatever the recent 30-year average is for rainfall in April, if it was 200% that amount this April then it's been a wet Spring.

And the start of 2024 was very wet ...

It's no surprise that many UK beekeepers had a poor season in 2024 ... a warm, wet Winter was followed by a warm, wet Spring.

My colonies had overwintered well and built up strongly before foraging proper started ... and then the rain continued to fall.

Everything stalled.

Migrant birds were delayed, and it was a struggle to get colonies into a suitable state for queen rearing.

Although June was slightly drier than average, it almost always seemed to be raining - often heavily - when I was supposed to be grafting, or when my virgin queens were out mating (or, not mating, as was usually the case).

I wrote about this in late June (The year without summer). My beekeeping - or at least my queen rearing - appeared to be blighted.

I was stalked from apiary to apiary by heavy clouds and cold winds.

Week after week I either packed up in disgust, got soaked to the skin, or failed to complete a fraction of what I'd planned.

Usually all three.

Little and often

I've been keeping bees in Scotland since about 2015. During that time I've reared quite a lot of queens, largely using methods I first learnt when previously living in the Midlands.

I usually start later in the year than I did further South, typically sometime in mid/late May, rather than April. I also finish earlier in the season, and have rarely experienced reliable queen rearing conditions in September (though loads of supersedure queens get mated successfully at that time of the year).

In addition to starting later and finishing earlier, the other things I've learnt (as always, the hard way) is that it pays not to 'put all your eggs in one basket'.

Setting up a triple brood box queenless cell raiser and adding 60 grafted larvae on a warm afternoon in mid-May makes a month and a half of continuous rain a near-certainty.

The cell raiser will need supplementing with syrup and pollen within days, many of the cells are likely to get torn down as the weather turns, the virgin queens - those that don't drown on orientation flights - will not get mated (at least not mated well) and the cell raiser and many of the mating nucs will develop laying workers.

Far better to produce a trickle of queens, a few cells a week, every week. Not only is this less likely to incite the weather gods into an unseasonal display of adverse conditions {{11}}, but it also means if the grafting fails, or the queens fail to emerge, or mate, or mate well, then you'll probably get another chance.

The best laid plans

However, although this approach is a little less resource intensive, it still needs good planning and preparation.

Which was probably where I first started to get things wrong. I was a bit distracted.

I'm not going to depress myself by recounting the failures, but they usually occurred after producing what looked like perfectly good, well-developed, queen cells. Typically, the virgin would not get mated, or would start laying and - seemingly within a couple of weeks - the colony would start superseding her. Several times I'd find the queen I'd grafted, together with the - soon to replace her - daughter.

And, in at least a couple of cases, the superseding queen failed as well 😢.

I was preoccupied with preparing to move and had little flexibility in the days/dates on which I could do my beekeeping. As a consequence, I feel as though I was in sync with the periodic bouts of bad weather, when I needed to be out of sync. Every time I needed it to be dry it was wet, and when it didn't matter (for example, when the cells were in my incubator) it was dry.

But, every cloud has a silver lining, and my queen-mating woes resulted in two beneficial outcomes:

- colonies not preoccupied with rearing brood busied themselves collecting nectar. At least one of my production colonies was still queenless when I took the supers off in early August {{12}}.

- it was easy to reduce colony numbers in June and July {{13}} by uniting, as I didn't have enough queens to go round.

I'm sure this increased my honey yield, and it meant there were no queens I felt sentimental about when reducing my hive numbers {{14}}.

Failures and non-starters

I had several attempts to get queens to lay directly in large Jenter-type cups (as described in the series of posts on Bigger queens, better queens). However, although not an unmitigated failure, these were less successful than I'd hoped. I already have plans to improve this for next year now I'm living in the sub-tropical Scottish Borders.

Ha!

The other thing that didn't happen this year was Taranov swarm control. If you already know what this is, I don't need to explain it. If you don't, then I hope you'll be able to read about it next year. The key point about this method - unlike almost all other methods of swarm control - is that it better reflects the partitioning of the colony during natural swarming, which is something I'm interested to try.

I carried a homemade Taranov board back and forth to the apiaries between May and July. Other than once using it as a grafting table, it remained unused. It's very well travelled. In 2025 I hope it's a bit less well travelled and used at least once.

And that, in a nutshell, sums up the beauty of beekeeping ... there's always another year, every year is different, and there are always different ways to do things.

Not necessarily better, just different ... though you don't always know this before you try it.

Ho, ho, ho!

Sponsor The Apiarist

If you enjoyed this post, please consider becoming a sponsor. Sponsorship costs less than three sheets of foundation a month or £1/week annually. Sponsors help ensure the weekly posts appear and have access to an increasing number of sponsor-only content (those starred ⭐ in the lists of posts).

Yes, you could rely on discussion forums for timely, unbiased and informed opinion, or you could risk a heady brew of Twitter, YouTube and simple guesswork, but is that really wise?

Alternatively, you can help reduce my caffeine overdraft ... and please spread the word to encourage others to subscribe.

Thank you

{{1}}: All these terms are relative ... warm means a bit over 7°C, and loosely clustered means they were together but didn't actually appear moribund.

{{2}}: Because I'm sure has hell it wasn't something I did do that made them a success.

{{3}}: It was, like all swarms reported in local newspapers, "huge".

{{4}}: Though rarely earlier in the season as the willow yielded really well.

{{5}}: To put this in context, I'd had no more than 10-15 kg in total over the previous 3 seasons, and got nothing at all in 2024.

{{6}}: It took ~15 seconds to fill a litre jug of water, which is approximately 0.5 bar pressure.

{{7}}: Actually, I had to look these prices up as it's over a decade since I bought an extractor.

{{8}}: That's an informed guess, based upon the efficiency of extracting summer/blossom honey in a radial extractor.

{{9}}: A term which apparently originated in the 1930's at the unfortunately named Camp Shatter where the Boy Scouts of America used the slogan "Every Scout is a Happy Camper".

{{10}}: Beekeeping, so much more than honey.

{{11}}: I don't actually believe there are such things as weather gods ... other than Set, the Egyptian god of chaos, evil and storm who I got to know very well this 'summer'.

{{12}}: And I don't remember getting any laying workers this season.

{{13}}: I'd decided to reduce colony numbers prior to moving, simply to make my life a little easier over the next few months.

{{14}}: Although I don't name my queens, I still dislike having to cull them unless it's really necessary.

Join the discussion ...