And then there was calm

Synopsis : The rush and bustle of the first half of the season is over and things are calming down. Time to reflect on some aspects of the season so far, and the importance of keeping good hive records.

Introduction

Over the past few seasons I’ve noticed that there is an inflexion point in the beekeeping season. It usually occurs a bit after the summer solstice, though the precise timing is variable. This is the time when I realise I’m no longer ’just keeping up’ (or sometimes ‘not keeping up’), but am instead finally ’in control’.

Perhaps those aren’t the correct terms?

It’s the point at which my beekeeping undergoes a significant change, from being ’reactive’ to something a whole lot more relaxing.

The variable timing of course reflects the behaviour of colonies in the preceding weeks; the early spring build up (Is it fast enough?), the – often startlingly rapid – mid-spring expansion and consequent swarm preparations, swarm control, queen mating (Has she? Hasn’t she?), the spring honey harvest and the need for additional feeding during the June gap.

All of which of course depends upon the weather and forage availability, explaining the variable timing.

And then, almost like a switch has been flicked – and with very little fanfare – the apiary feels a lot calmer.

There are no unexpected swarms hanging pendulously in nearby bushes, no real surprises when I open the hives, and no ’catch me if you can’ virgin queens scuttling about.

Instead, the bees are just getting on doing exactly what they should be doing and – significantly in terms of my reactive vs. passive beekeeping – exactly what I expect them to be doing.

It’s all downhill from here

As I left one of my Fife apiaries on Tuesday evening I realised that we’ve just passed the inflexion point this season.

All the colonies were doing pretty well. Laying queens were laying well, though not as fast as a month ago, foragers were starting to return with increasing amounts of summer nectar {{1}} and supers were beginning to fill.

Of course, not every hive is at exactly the same stage. A few are queenless, or contain unmated virgins. However, even these hives are behaving largely as expected.

Whilst it’s a bittersweet moment, it’s also reassuring to feel on top of things.

Bittersweet because it means the bulk of the ‘beekeeping’ in my ‘beekeeping season’ is over.

Hive inspection frequency reduces from once a week to once a fortnight or even every three weeks. After all, the colonies are queenright, the new queen is laying well and they’ve got space for brood and stores … what could possibly go wrong?

A few things … but they’re much less likely to go wrong in the second half of the season to the first.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that there’s not still work to do.

The summer honey harvest will be busy, or at least I hope it will. It’s just starting to pick up, with the blackberry and (often not very dependable) lime.

That’s followed by the season’s most important activity – the preparation for winter and Varroa treatment. Without these I might not be a beekeeper next year.

However, none of these ‘second half’ functions are likely to produce any unwanted surprises – it should all be plain sailing.

The enjoyment of uncertainty

My move from the east coast to the west coast of Scotland has resulted in new challenges – more changeable weather, different forage availability – and I’ve still got a lot to learn here.

In contrast, despite the inevitable season-to-season variability, I feel reasonably confident with my east coast bees (I still have bees on both sides of the country). Only ‘reasonably’ because they can still produce the odd surprise.

However, with every additional year of beekeeping, I’m much less likely to be faced with a ”What the heck is this hive doing?” situation between now and late September than from April to June.

The challenges are one of the things I really enjoy about beekeeping. It keeps me on my toes. Identifying the problems and (hopefully) solving them improves my beekeeping.

Even not solving them – and there have been plenty of those over the years – means I learn what not to do next time.

For some situations I’ve got a long mental list of what not to do … though little idea of what I should do.

No worries … perhaps I’ll learn next year 🙂 .

Weather dependence and queen mating

Three weeks ago I mentioned one of my queen rearing colonies had torn down all the developing queen cells, probably in response to the emergence of a virgin queen below the queen excluder. The box was set up with a Morris board, so was rendered queenless while starting the queen cells, and then queenright when finishing them.

One of the things this experience reinforced was the importance of continuing inspections on a queenright cell rearing colony.

Just because things all look OK above the queen excluder {{2}} doesn’t mean that it’s not all going ’Pete Tong’ in the brood box.

My records showed that I had checked the brood box on the 18th of May when I set up the Morris board. Grafts were added on the 25th and were capped on the 30th.

By the 1st of June they’d all been torn down 🙁 .

On finally checking the bottom box early on the 4th of June I found a virgin queen scurrying around.

Mea culpa.

The original queen had been clipped. The colony had presumably attempted to swarm around the time the virgin emerged – or perhaps a little earlier – and resulted in the loss of the clipped queen {{3}}.

And then, as we segued into the second week of June, the weather took a turn for the worse.

Pollen

I watched for pollen being collected by foragers on flying days. It’s often taken as a sign that the hive is queenright. However, good flying days have been few and far between. I’d also been away quite a bit and there’s not a huge amount of pollen about at this point in the season.

However, is it a way to discriminate between queenright and queenless colonies?

I’ve watched known queenless colonies that are still collecting pollen, though perhaps at a lower rate than one with a mated, laying queen.

Do you remember the recent discussion about queenless colonies ’Hoping for the best but preparing for the worst.’ and preferentially drawing drone comb? Those drones will still need a protein-rich diet, so the colony – if it is to have has any chance of passing its genes on – will probably still collect pollen to feed the developing drones.

This particular colony was collecting pollen and was well behaved when I had a brief look on the 10th of June. My notes stated: ’Behaving queenright, but no eggs 🙁 ’.

On the 22nd of June, the next time the weather and my availability allowed a check, my notes were fractionally more upbeat: ‘No sign of Q or eggs, but no sign of laying workers either (let’s look on the bright side)’.

And then – on my next check – the 29th, there was a small patch of eggs, perhaps 2-3 inches in diameter 🙂 .

My notes this time were a bit shorter: ’Hu-bloody-rrah!’.

I also did some back-of-an envelope calculations which indicated that the egg used to rear the queen was probably laid on the 16th of May, and she was known to be laying 44 days later.

Flying days and mating days

I usually reckon – based upon published literature and accounts from much more experienced beekeepers – that a queen must mate within 4 weeks of emergence {{4}}.

It looks like this one just met that deadline.

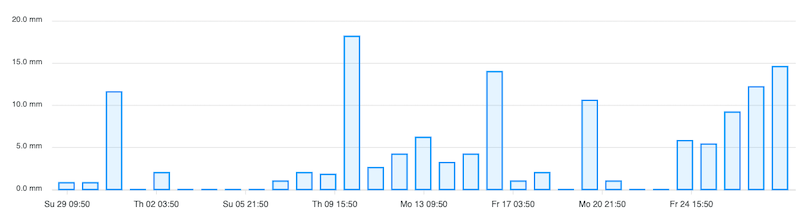

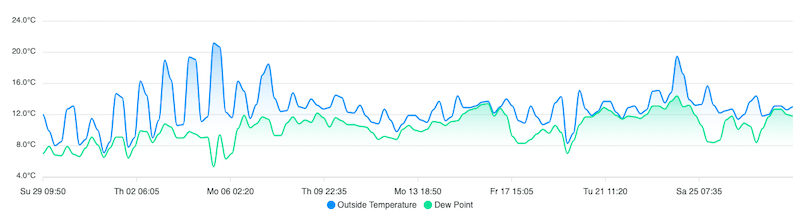

We had good weather in the first few days of June, but the middle fortnight was cold and/or wet, with the temperature rarely exceeding 14°C.

Assuming the queen emerged on the last day of May she probably probably went on her orientation flights in the good weather at the beginning of June.

As an aside, I’m not sure of the weather-dependence for queen orientation flights. For workers – based upon hive entrance activity – it’s pretty clear that they preferentially go on these flights on warmer days. However, if queens restricted themselves to good weather – particularly in more northerly climates – they might limit their chances of making successful mating flights. Perhaps queens go on orientation flights even if the weather is sub-optimal, so that they’re ready {{5}} when there’s a suitable ‘weather window’ for mating flights?

Anyway, back to this queen … I doubt she went on her mating flights in early June because there were no eggs in the colony when I checked on the 10th or the 22nd. My eyesight isn’t perfect, but I looked very carefully. There were definitely ‘polished cells’, but no eggs.

The temperature reached a balmy 19.4°C on the 24th of June (a day with only 7mm of rain!) and she was laying a few days later.

Being able to relate queen age with the weather helps determine whether she may have missed her chance to mate successfully. This is important in terms of the development of laying workers, or the colony management to avoid this.

The extremes of the season

For those readers living in areas where the weather is a lot more dependable this might not be something you ever think about.

Queens just get mated.

No pacing backwards and forwards in the apiary like an expectant father {{6}} waiting for the good news.

Lucky you.

But, there are times when this weather dependence might be relevant. Early or late in the season it’s likely that the weather will be wetter, windier and cooler. At those times you also need to think about the availability of sufficient (and sufficient quality – they decline later in the season) drones for queen mating.

Queen rearing – or queen replacement of a colony that goes queenless – might be successful, but is it likely to be dependably successful?

On the west cost of Scotland this enforces a ‘little and often’ regime to my queen rearing. Rather than using lots of resources to produce a dozen or two at a time I do them in small batches. Some batches fail – grafts don’t ‘take’, colonies abandon cells, queens fail to get mated – but others succeed.

I’ve got a batch of mini-nucs out in the garden now, and will probably try one or two more batches before the season draws to a close.

Our most dependable (and these things are all relative 🙂 ) pollen and nectar is the heather which is still a fortnight or so away. If that coincides with good weather then there’s a good chance for some late season queen rearing.

Global warming

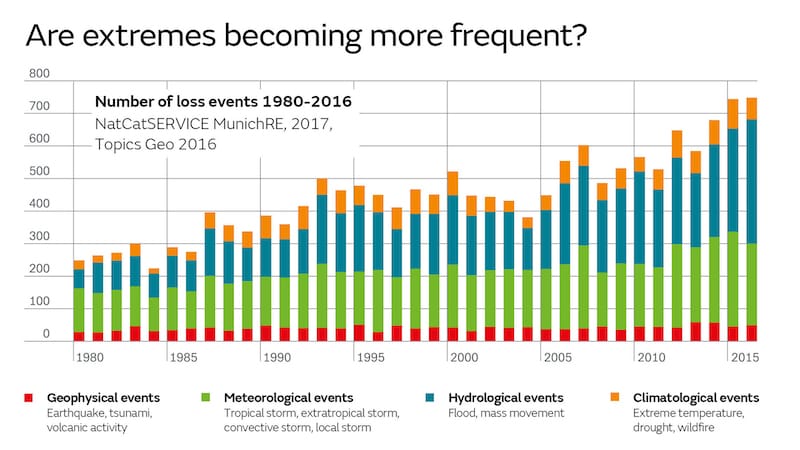

But don’t forget global warming. This affects all beekeepers whether living in the balmy south or the frozen north. Global warming, and more specifically climate change, is leading to more weather extremes.

Warmer, wetter and windier is the likely forecast. The first of these might help your queen mating, but torrential rain or gale force winds will not.

And that’s before you consider the impact on the forage your bees rely upon … which I’ll deal with another time.

More misbehaving queens

The conditions for queen rearing on the east coast of Scotland are far more dependable. I’ve been busily requeening colonies, making up nucs and clipping and marking mated queens for the last couple of months.

Most of this has all been very straightforward. All of it forms part of the ’reactive’ part of the season I referred to above.

If a colony makes swarm preparation I make up a nuc with the old queen and leave the queenless colony for a week. I then destroy all the emergency queen cells and add a mature queen cell or a frame of eggs/larvae – in either case derived from a colony with better genetics.

In due course the new queen emerges, gets mated and starts laying. I then mark and clip her.

This time last year I discussed a queen that fainted when I picked her up to clip her. That queen recovered, I clipped and marked her the following week without incident and she is still going strong.

Although I’d never seen it before, It turned out that several readers had experienced the same thing, so it’s clearly not that rare an event.

Pining for the fjords? {{7}}

One of my good colonies – #38 in the bee shed – started to make swarm preparations in the third week of May. I removed the old queen to a nuc, left the colony for a further week and then reduced the queen cells, leaving just one which subsequently emerged on the 2nd of June (I also ‘donated’ one spare queen cell to a neighbouring hive that was also making swarm preparations).

Colony #38 wasn’t checked again until the 20th {{8}} when I found a good looking mated, laying queen.

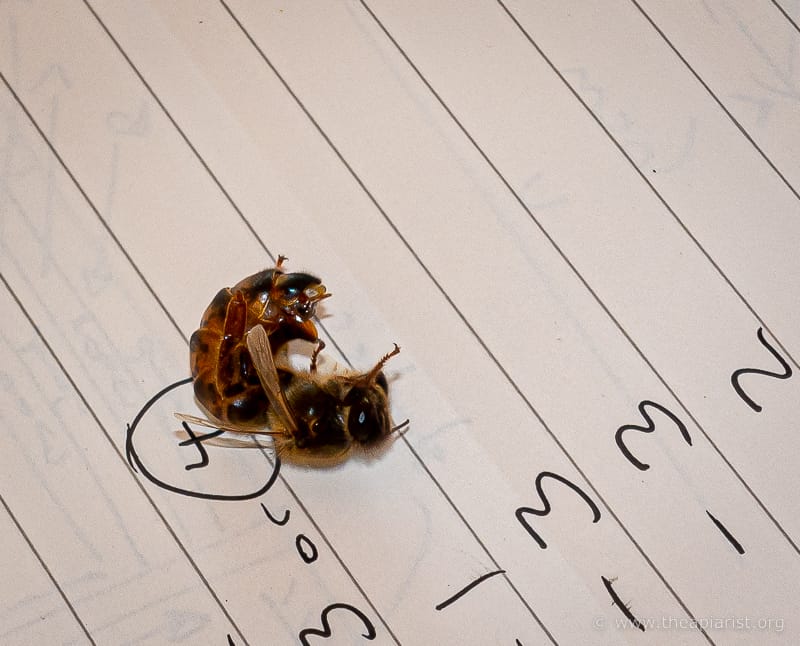

I gently picked her up by the wings.

She didn’t feint 🙂 .

She died 🙁 .

At least, I’m pretty sure she died.

She curled up into a foetal position and showed no movement for 15 minutes. There might have been a slight twitching of an antenna, but the regular expansion and contraction of the abdomen during breathing was not visible. I wasn’t even certain her antennae moved.

I had other hives to inspect so I popped her into a JzBz queen cage and left her with the colony whilst I got on with things.

When I returned – an hour or so later – she was still looking like an ex-queen.

I had little choice but to leave her lying on a piece of paper underneath the queen excluder {{9}}. She was quickly surrounded by a group of workers.

I closed the hive up, crossed my fingers {{10}} and went off to another apiary.

Like mother, like daughter

The following week the colony was indisputably queenless.

Their behaviour was less good and – a much more definite sign – they had produced a number of emergency queen cells from eggs the queen had laid. I knocked all the queen cells back and united colony #38 with another hive.

One week later they were successfully united.

Only later, when comparing my notes with last season, did I realise that the queen that died was a daughter of the queen that fainted last year. I wonder whether the ‘dropping dead’ is just a more extreme version of the fainting I had previously observed?

This implies it might be an inherited characteristic (as at least one of the comments to the fainting post last year suggested).

For clarity I should add that I’m certain that I didn’t directly harm the queen when I picked her up. She was walking around very calmly on the frame. I waited until she was walking towards me, bending at the ‘waist’ (either to inspect a cell, or crossing a defect in the comb) so pushing her wings away from the abdomen. I held her gently by both wings and immediately dropped her into my twist and mark cage.

No fumbling, no squeezing, no messing.

I’ve done this a lot and it was a ‘textbook example’.

Except she never moved again 🙁 .

And like sister?

If, as seems possible, this is an inherited characteristic it will be interesting to see whether the neighbouring colony I donated the spare queen cell (from colony #38) to also shows the same undesirable phenotype {{11}}.

Not so much ‘playing dead’ and ‘being dead’ when handled.

The original fainting queen is currently heading a full colony in another apiary. I’ve had no cause to handle her since last June. She didn’t faint the second time I picked her up (for marking) but I might see how she reacts next time I’m in the apiary.

If she faints again, and particularly if the sister queen reared this season faints (or worse 🙁 ), I’ll simply unite the colony with another.

Firstly, it will be getting a bit late in the season for dependable queen mating and, secondly, it’s clearly an inherited genetic trait that I do not want to deal with in the future.

It doesn’t really matter how gentle, productive or prolific the bees are if the queen cannot cope with being (gently but routinely) handled. It doesn’t happen often, but the risk of ending up with a corpse when I manhandle her into a Cupkit cage, or have to repeat the marking, makes some aspects of beekeeping impractical.

But look on the bright side … it will be a very easy phenotype to detect and select against 😉 .

Hive records

If there is a take home message from these two anecdotes it’s that good hive records are both useful and important. They help with planning the season ahead and avoiding real problem areas of colony management.

I use a (now propolis encrusted) digital voice recorder (and spreadsheet) when inspecting multiple hives

Far better to know that the queen is almost certainly too old to mate than continue to hope (in vain) that it’ll work out. If you are certain – within a day or two – of her emergence date you can intervene proactively (e.g. by uniting the colony, or supplementing it with open brood) to delay or prevent the inevitable development of laying workers.

By also watching the weather you can also work out when she should have been able to get out and mate.

Similarly, by keeping a pedigree (which sounds fancy, but needn’t be) of your queens, you can avoid selecting for undesirable traits. These fainting/dying queens might be unusual, but there are other behaviours that might also be avoidable.

The original queen in colony #38 might have been a ‘one off’, but if her daughters also behave similarly then I should avoid using them to rear more.

To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, “To lose one fainting queen may be regarded as unfortunate, to lose two looks like carelessness poor record keeping”.

{{1}}: The June gap has been really pronounced this year.

{{2}}: For an introduction to queenright queen rearing, which I don’t have time to describe here, have a look at my previous posts on the Ben Harden system.

{{3}}: My subsequent calculations suggest that the queen emerged on the 31st of May.

{{4}}: Some quote 21-28 days, and there’s likely some variation.

{{5}}: Hot to trot?

{{6}}: A woefully out of data analogy … I’m aware that partners have been allowed in the delivery room for decades.

{{7}}: A reference to the Dead Parrot Sketch by Monty Python.

{{8}}: I’d made intermediate visits but there was little point in unnecessarily rooting around in the brood box.

{{9}}: It was that or nail her to the comb.

{{10}}: Of course, this is a metaphorical crossing of fingers. Firstly I don’t believe in that nonsense and secondly it’s very difficult to complete a hive inspection with crossed fingers.

{{11}}: The observable physical characteristics, as determined – at least in part – by the genotype (the genetics).

Join the discussion ...