Contact killer

As the days get shorter and the beekeeping season becomes just a fading (happy) memory, visitor numbers to this site start to dwindle. Still healthy {{1}}, but perhaps only 30% of the numbers in May and June.

This is partly because there seems to be less to do at this time of the season.

No swarming, no queen rearing, no honey to harvest … and for many, no real thoughts of beekeeping.

It’s also undoubtedly because the voracious ‘read all you can’ beginners now have several months beekeeping experience.

Some are likely to think they know it all already {{2}}.

Others may have given up in disgust when their colony swarmed (again) in August and they ended the season dispirited, queenless and honey-less 🙁

Of course, some beekeepers will be aware that, although there are some winter (or late autumn) tasks, there is no rush … there’s a whole winter ahead to deal with these and everything should then be fine until the season starts.

Au contraire as we used to say before Brexit 🙁

The paradox of timing miticide treatments

There remains one critically ‘time sensitive’ task to complete before the bees are ready for the season ahead.

Or, as I shall show shortly, not time sensitive with regard to the calendar, but time sensitive with regard to the state of the colony.

Not feeding … that should already be complete and they should not need topping up (if at all) until brood rearing really starts to ramp up in the early spring.

What needs to be done is to kill the mites – or as many as you can of them – that survive after the late summer/early autumn miticide treatment.

There’s an interesting paradox in miticide treatment …

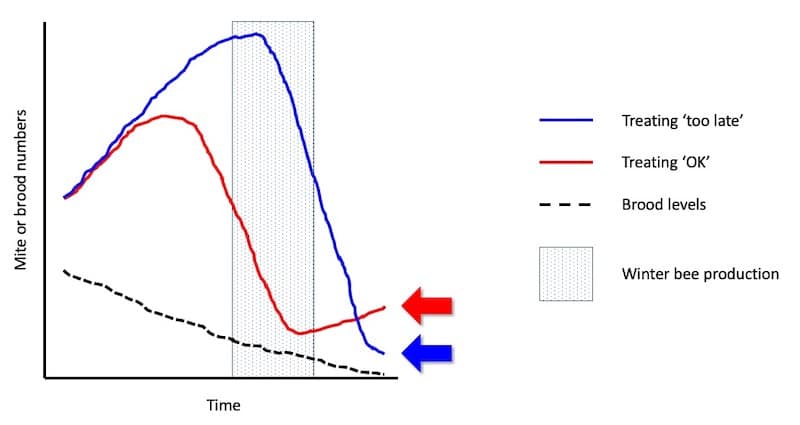

The earlier you treat for mites once the summer honey has been removed, the more mites are present in the hive at the end of the calendar year. If you think about this – or look at my crudely drawn diagram {{3}} – it should be obvious why this is:

If you treat early enough (red line) to protect the winter bees from the ravages of Varroa and viruses, the mites that survive treatment will continue to reproduce in the small amount of brood reared at the end of the season (red arrow).

In contrast, if you treat too late to protect the winter bees (blue line), the surviving mites will have nowhere to reproduce as brood rearing will have stopped (blue arrow).

And there will be surviving mites.

None of the approved miticides {{4}} will kill more than 95% of mites in the hive {{5}}.

Survivors

So, to start next season with the minimal mite load, you really need to kill as many of these surviving mites as possible.

The usual choice for a ‘midwinter’ mite treatment is oxalic acid. This can be trickled or vaporised and, under optimal conditions, kills 90-95% of the mites. You only need to administer it once and it is reasonably well tolerated by the bees {{6}}

Let’s assume there are 200 mites remaining in your colony after the late summer miticide treatment and the last little flurry of mite hanky panky reproduction in the final round or two of brood reared by the colony.

If you can kill 90% of these mites with a single OA treatment there will only be 20 mites remaining at the beginning of the following season.

But can you kill 90% of them?

Oxalic acid is only effective against phoretic mites. Any mites lurking in capped brood cells will escape treatment. Therefore, if some, most or all of those 200 mites are in capped cells there will be significantly more remaining at the start of the following season.

During the active brood rearing season it has been determined that ~10% of mites are phoretic at any one time. Unfortunately, I’m not aware of any similar studies for the proportion of mites that are phoretic outside the spring and summer.

So, in the absence of any hard data let’s do some arbitrary arm waving calculations … 😉

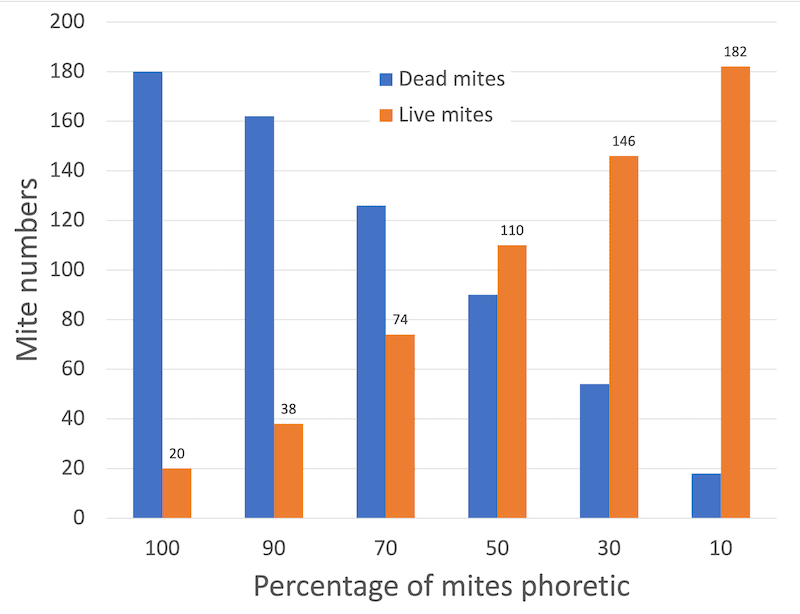

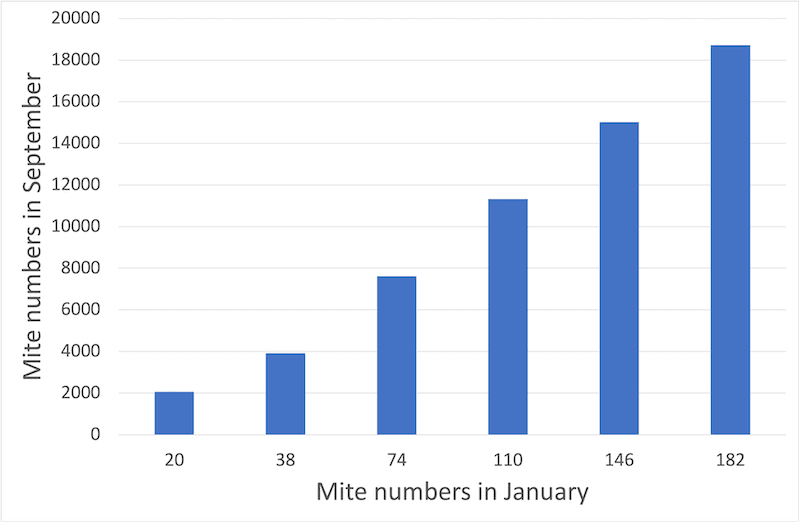

The graph below shows the numbers of mites surviving a 90% {{7}} oxalic acid treatment where the percentage of phoretic mites ranges from 100% to 10% i.e. a range covering everything from a totally broodless colony to one with excess brood in all stages for the mites to parasitise.

Total mite numbers surviving OA treatment depends upon the proportion that are phoretic when treated

Unremarkably … the greater the percentage of mites that are phoretic, the fewer mites are left in the hive after the oxalic acid treatment.

And, equally unremarkably, for a contract contact killer {{8}} like oxalic acid, it is only when all the mites are phoretic that 90% of the original 200 mites can be killed. As you can see from the graph, if only 50% of the mites are phoretic, 55% of the total number of mites in the hive will survive treatment.

If you look at the 10% phoretic column you will understand why a single oxalic acid treatment in the height of the season – or for that matter dusting with icing sugar (which is even less effective) – has only a very limited impact on the overall mite numbers. If only 10% of the mites are phoretic then a whopping 91% of the mites (182) will survive.

Whopping?

Aren’t these are all quite small numbers?

20, 74, 146?

What’s a handful of mites between friends?

Does it really make a difference whether your hive contains 20 or 74 or 146 mites at the beginning of the following season?

Yes, it does.

It makes an enormous difference.

The mites present in early January will reproduce as brood rearing ramps up in spring. Therefore, at any particular time point in the season – assuming all other things are equal – there will be a significantly higher mite load in a colony that started the year with more mites, than one that started the year with fewer mites.

We know quite a bit about the reproduction of Varroa. For example, we know more progeny are reared when feasting on drone rather than worker pupae (because of the longer duration of pupation). There are a host of additional parameters that influence the reproduction rate of the mite population – the proportions of drone to worker brood, the availability of brood, the duration of the phoretic phase of the life cycle (in turn, likely influenced by the availability of suitably aged nurse bees) and so on …

All of which means that we can predict the number of mites present in a hive during the season based upon the number of mites at the start if we make a series of assumptions of hive strength, time of the season, rate of colony build up etc.

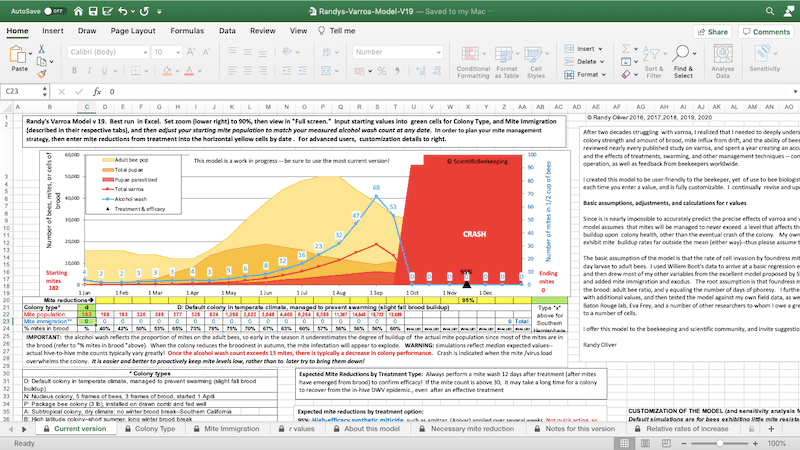

I used to use the BEEHAVE software to do this type of colony modelling. However, recent changes to the programming language {{9}}) means BEEHAVE now barfs a slew of error messages back at me when I use it. Since I’m not keen to try and patch up something that is based on outdated or deprecated libraries I’ve instead been dabbling with Randy Oliver’s Varroa Model which is Excel-based.

Many of you will know Randy as a regular contributor to the American Bee Journal, a commercial beekeeper and the author of scientificbeekeeping.com.

Modelling mite numbers

Using this mite calculator you can easily predict how mite levels build up over the season.

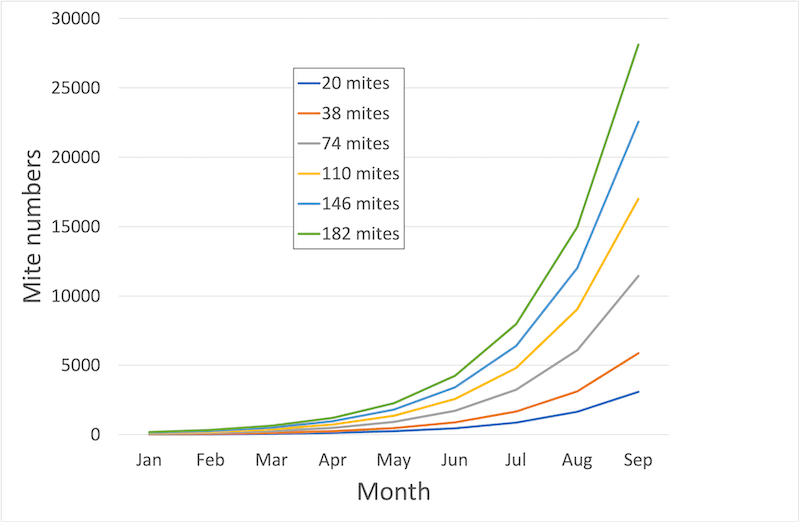

Assuming there was an excess of brood available throughout the season (there isn’t as I shall explain shortly) you could expect mite numbers to increase 154-fold between January and September.

Therefore, if you started the season with just 20 mites there would be ~3000 in the hive by the time the colony is rearing the winter brood in September.

Conversely, 182 mites in January would multiply to over 28,000 by September 🙁

Of course, there is not an excess of brood available throughout the season. For example, in the early spring brood is limiting. However, we can factor brood availability by modifying the calculations to take account of colony strength and build up, reinfestation rates and the proportion of drone brood being reared in the hive.

All of which has conveniently been included in the Varroa Model … thanks Randy 🙂

These various limitations inevitably restrict mite reproduction and the fold-increase between January and September is ‘only’ about 100. This means that a colony that started the season with 20 mites will contain just over 2,000 by September, whereas a colony that started with 182 mites will end up with over 18,000 by the end of the summer.

18,000 is a lot less than 28,000 … but it’s still a humungous number of mites.

Or, more scientifically, it’s an infestation level that the colony is unlikely to survive. 18,000 mites is probably well over one mite for every two adult bees in the colony. With that level of mites you can expect every pupa to be parasitised.

The colony is doomed.

You can check these numbers if you want. The Varroa model is freely available from scientificbeekeeping.com and is well documented. I used V19 for the calculations above. I also used the model with almost all of the default settings unchanged {{10}} – specifically this was the colony type Randy designates ‘D’ meaning Default colony in temperate climate, managed to prevent swarming (slight fall brood buildup). The only change I made was to set mite immigration (drifting) to 0.

Are you now convinced of the need to treat in ‘midwinter’?

The ‘midwinter’ mite treatment needs to be applied to minimise the mite levels the colony starts the season with the following year.

However, to be maximally effective, this ‘midwinter’ treatment needs to be applied when all of the mites in the colony are phoretic. That means that winter oxalic acid trickling (or vaporisation) needs to be done when the colony is broodless.

Not when it’s convenient for the beekeeper because s/he is getting over an excess of mince pies and port in the now almost universal holidays between Christmas and New Year’s Day.

‘Midwinter’ is not in the middle of winter … beekeepers should (mis)use the term in the same way they (mis)use phoretic … i.e. not literally.

Brood rearing – if it ever stops (which I’ll return to at the end) – probably restarts around the winter solstice. That means that there will be sealed brood in the colony early in the New Year. I don’t know how much of that brood is likely to be infested, but I do know that any that is infested will inevitably mean that I’ll be killing fewer mites than I could … and therefore that I’ll be risking exposing the colony to much higher mite levels later in the season.

We’re now in mid-November. Almost all beekeepers should have completed their late summer miticide treatment by now. My Apivar strips were removed almost a month ago.

The precise timing of the ‘midwinter’ mite treatment is irrelevant as long as it coincides with a broodless period in the colony.

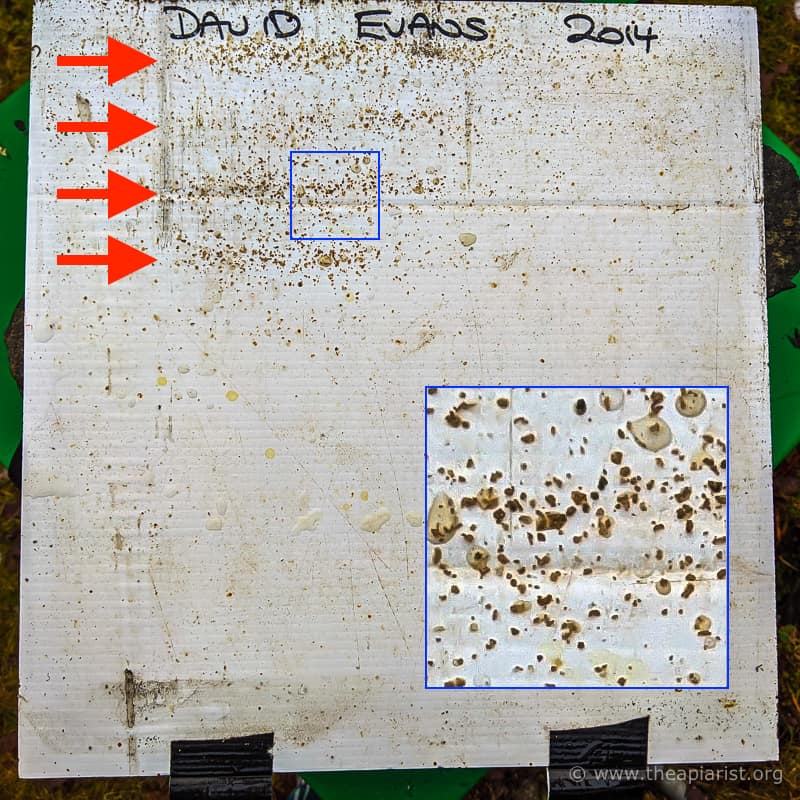

I therefore monitor brood production in my colony from late October onwards. As soon as the colonies are broodless I treat with oxalic acid.

There is nothing to be gained by waiting until later in the year. A phoretic mite is a phoretic mite … once they’re unable to hide away I’ve got a 95% chance of killing them.

Those are my sort of odds 😉

I’ve previously discussed how to monitor for a broodless period. If you don’t want to open the hive then learn how to read the debris on a Varroa tray. It’s not witchcraft or rocket science.

I expect my colonies to be broodless next week. It’s a little later than last season, but we had warm weather through much of the early autumn. If they’re not broodless yet I’ll hold off treatment for a fortnight or so. Past experience has taught me that the colonies (here in Scotland) are almost inevitably broodless for at least 2-3 weeks between late October and mid-December.

And, if your colonies are never broodless in the winter, all of the above still applies … except you have the slightly more difficult task of identifying when there is the minimal level of sealed brood in the colony.

Why the minimal level?

Because, unless there are weird things like multiple mites infesting each cell, it is logical to assume that when the brood level is at a minimum the phoretic mite level will be at a maximum.

Global warming

As we reach the end of a not-altogether-convincing COP26 conference I thought I’d also mention a recent paper by Giles Budge and colleagues in Newcastle.

I have found it is easier to manage mite infestation levels in Scotland than when I lived in the Midlands. I have a lot more flexibility in the timing of the winter treatment now as the colonies are broodless for longer.

With global warming we can expect warmer winters and therefore it’s probable that colonies may have sealed brood for more of the calendar year.

That will make mite management more difficult.

Certainly not impossible though … particularly if you learn now 😉

Notes

A major power outage has meant this was written by candlelight and hot-spotted mobile phone connection. Once power is restored I’ll go back and tidy some of the text and add the keywords. In the meantime I’ll fire up my trusty Ghillie kettle to make another brew 😉

{{1}}: I’d like to thank you both for being so loyal.

{{2}}: Spoiler … you don’t. I’m well aware that I don’t and I already have several successful seasons under my beesuit belt.

{{3}}: Very crudely, but this was being written during a major power outage and I didn’t have the luxury of getting it anything like perfect.

{{4}}: And none of the homegrown recipes or various ’Snake oils’ or ‘magic cures’ offered via social media.

{{5}}: Why not? One of the reasons is that the miticides are also detrimental to the bees … if you used them at a high enough concentration, or for long enough, to kill 100% of the mites you would also probably damage the colony.

{{6}}: Only ‘reasonably’, as dribbled OA damages unsealed brood, but the benefits to the colony – in terms of mites slaughtered – probably still far outweighs the brood damage caused.

{{7}}: I’m being conservative here … I could have chosen 95% but it would have just changed the overall numbers a bit, not the point I’m trying to make.

{{8}}: Apologies … one of my poorer titles.

{{9}}: An unpleasant brew of Java and NetLogo … urgh!

{{10}}: It’s worth noting that some of these defaults may be wrong for UK beekeepers … the volume of the hive, the size of the colony, the duration of the foraging season etc.. However, none of these differences alter the basic principles of mite reproduction. The final numbers might be slightly different, but that’s all.

Join the discussion ...