Did they not read Seeley?

The first swarm I saw this year arrived in my bait hive — pre-announced by a flurry of scout bee activity — on the 10th of May. I discussed its arrival, and that of two others in the same week to the same bait hive, in an earlier post.

With all that activity, I think I can be confident that swarming started in my little bit of the Scottish Borders, in the second week of May.

What about the rest of the UK?

From a phenological standpoint this would be interesting data to have, but I suspect it's either non-existent, or buried in the calls logged by 'swarm-line' operators from beekeeping associations around the country {{1}}.

I've not tried to access these, and I'd be interested if anyone has. With it, together with weather data for March to May (over several years), we could try to relate one to the other, and have something usefully predictive for the future.

Lateral thinking

There are other potential information sources that could be examined.

I could scour social media for mention of the word 'swarm', but it's a) lacking any geographic context, and b) full of misogynists and conspiracy theorists. The first of these causes issues with data analysis, the second makes accessing it unpleasant.

No thank you.

Why not sponsor The Apiarist?

Sponsors of The Apiarist receive a newsletter on the science, art, and practice of sustainable beekeeping every week, at least 50% of which are for sponsors only. Sponsorship supports my research and writing, and costs about the same as a coffee and doughnut a month, or less annually … go on, you know it makes sense.

What about looking closer to home?

I've been writing long enough, and Google has indexed my posts often enough, that some stuff I've written is read {{2}} thousands of times a year. I also collect limited geographic information on where people access the site from (at least at a first approximation, there will be VPN or Tor users buried in the counts, but many beekeepers are rather low-tech, so I'll assume these are small numbers).

This activity is seasonal; posts on miticides are mainly read in late summer, whereas posts on swarm control get more interest, er, when swarming starts.

In this image, 40% of the page accesses were from the UK. The page listed (on the left) as '/' is the site homepage. Page views remain broadly the same all year. Likewise, 'Mad honey' shows little seasonal bias.

In contrast, pages on swarm control methods, like the nucleus method and Pagden's artificial swarm, show a distinct uptick at the end of March (28-30th), remain popular during April, and then start to tail away after mid-May. The Demaree method is more correctly a swarm prevention technique, perhaps explaining its popularity before April.

My best guess — without further detailed inspection of the server logs {{3}} — is that the first swarms in the UK occurred as an unusually warm and dry March segued into an even warmer, and drier, April.

Summer swarms

But swarming didn't stop by the end of May. Late developing colonies, or even fast-expanding early swarming colonies, can swarm later in the season. These don't register on my page accesses; the interest is diffusely spread between May and late July, and lots of other topics are getting more attention.

But, if you've got a bait hive or two, and are reasonably observant, you'll periodically notice scout bee activity.

Between late May and the end of July I've seen two or three bouts of scouting activity at my garden bait hive, though none have led to a swarm arriving.

One of these periods of scout bee interest was around the 8th and 9th of July. Scout numbers reached 20–30, but then started to dwindle. The following day, while walking the dogs in the nearby wood, I noticed scout bees checking out the base of an oak tree. I was there again on the 11th and the bees were busy, showing very obvious scouting behaviour.

Scouting activity at the base of a small oak tree, mid-July 2025

Notice how few bees are entering the cleft in the tree. Most are hovering around the entrance. The video quality is too poor to show it, but no bees were carrying pollen and there were no drones present.

And, when I went past a week later, the swarm had moved in. My video is even worse (so I'm not showing it, but it's available if you want) but the bees were now directly entering the cleft. Pollen-laden foragers were present and there were also a few drones buzzing noisily about {{4}}.

“They've got it all wrong”, Seeley didn't say.

Scout bees exhibit strong biases when searching out, and promoting, suitable new nest sites. I've discussed these in gruesome detail in previous posts as they provide the broad 'design spec' for any bait hives we set out (at least if we want to meet the requirements of scout bees and swarms, and therefore have the best chance of attracting a swarm).

A far more eloquent description of the desirable features of a nest site is provided in Thomas Seeley's Honeybee Democracy.

How do these desirable features (in bold below) compare with the site illustrated above?

40 litre void volume : Without taking a chainsaw to the tree this will remain an unknown. However, the trunk has a diameter of ~40 cm at chest height, so if the void is 40 litres it must extend some way up the tree.

Small entrance : Although the cleft in the tree is relatively broad, it narrows considerably at the apex, which is how the void is accessed. I've watched the bees repelling wasps, so I presume it should be relatively easy to defend.

South facing entrance : Not even close. In fact, the entrance faces North, North-West.

Entrance 5+ metres above ground : Epic fail. It's not even 50 cm above ground. Fortunately, black bears are few and far between in the Scottish Borders, so the bees should be OK.

Old comb or smelling of bees : Again, without using my 'Trusty Husky' this will also remain unknown. However, there's a small pile of particulate debris below the nest entrance (see header image), so I wouldn't be at all surprised if it was previously occupied by bees, though this would have been before August '24 (when I moved here).

None of this means that our understanding of the preferences exhibited by swarms are incorrect … they are preferences after all, not absolutes. I'll still set out my bait hives as I've always done, but I'll also remember to look more widely when searching for free-living colonies.

I see bees almost every day, but it's lovely to see a colony occupying a more natural site than an Abelo poly hive.

Particularly since they're at knee-height, and I'll have the dogs with me 😄.

But are they free-living?

Not yet, they're not.

They've only just arrived, and — based on the likely day of occupancy — the first brood reared in the tree has yet to emerge.

To be counted as free-living they need to at least survive the coming winter, and then generate a surviving swarm next year to ensure that the population is self-sustaining.

Although this area has relatively few beekeepers (compared to the South-East of England, not the highlands of Scotland), I suspect that the swarm originated from a (mis-)managed hive, rather than from a free-living colony elsewhere in the local woods.

This is little more than an (ill-)informed guess; the woods here are not hoaching with bees, and I'd expect free-living colonies to have already swarmed this year (so unlikely to swarm again). In fact, I think one of my May swarms may have come from a free-living colony, based upon its arrival direction (from the howling wilderness to the East of me) and size.

I'll keep an eye on the tree over the next few months and hope to watch them thriving.

I've also reported the location to the long-running Citizen Science project organised by Magnus Peterson (University of Strathclyde) that monitors feral colonies in Scotland. This survey has been running for ~16 years and is based upon biannual reports (in April and September) from which things like survival and re-colonisation of sites can be determined.

Which conveniently brings me to a recent publication on a similar, but larger scale, Citizen Science project monitoring free-living honey bees in Germany (Rutschmann et al., 2025).

This study has done the all-important 'ground-truthing' of the 'Citizen' bit of the Science, so providing information on how valid results obtained like this are.

BEEtree-Monitor (2016-2023)

This is the name of the Citizen Science project. Over 7 years, 2555 observations on the longitudinal occupation of 530 nest sites were collected; 20% of the nests were monitored by the scientists running the project, and 80% by the 'citizens' that generously contributed.

By comparing some of this data it's possible to get an insight into the validity of these types of Citizen Science project, as well as identifying problems with the methods used e.g. overwintered survivors being reported after swarming starts.

The methodology and the paper are easy to follow (and the paper is Open Access, so anyone can download it), so I'm just going to focus on a few of the points that I found particularly interesting.

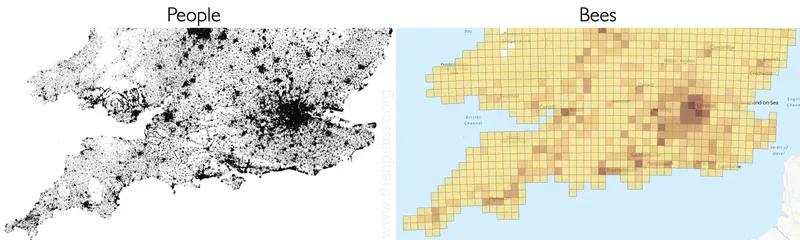

More people live in urban areas than rural ones. It's therefore not surprising that more free-living colonies were reported in urban areas.

Not only are people living in towns more likely to discover honey bees in their locality, but there are also higher densities of managed colonies in urban areas (so generating more occupying swarms).

Free-living bees predominantly occupied nest sites in trees in both urban (52%) and rural (68%) areas, with buildings a close second in towns, and a distant second in rural areas. Lime trees — a popular choice for town planners — were the most frequently occupied, though oak and beech predominated (unsurprisingly) in the oak and beech forested areas.

In terms of nest site choice, tree-dwelling colonies favoured South-facing entrances 4–5 metres above ground level (these bees clearly had read Seeley's Honeybee Democracy 😉), though those in buildings showed no directional bias, presumably because sites in buildings are evenly distributed {{5}}.

No real surprises so far, but a nice large dataset, and valuable independent verification of previous studies.

These words don't just appear by magic (or involve ChatGPT) … it takes research, drafts, editing, proofing and lots of coffee ☕. If you find these posts interesting, useful or informative, but would prefer not to become a sponsor, then please consider maintaining by blood caffeine levels to ensure the next post gets written on time (use this button, or the coffee mug in the corner).

What about survival?

The survival over 343 colony winters was recorded (some colonies being recorded over successive winters), 44% by Citizen Scientists (CS) and 56% by the team leading the study (which they termed 'personal monitoring; PM', which I'll use for convenience).

This is where things started to get interesting.

Over the 7-year study period ~29% of colonies monitored by CS survived overwinter, compared to only 13% monitored by PM.

Why this large difference?

It's unlikely to be regional, or habitat variation, though both undoubtedly do exist. The scientists could not cover the entire country, whereas the 'citizens' reporting did.

By analysis of the data it was clear that PM sites were much more closely monitored than CS sites. 59% of the latter were not reported on early the following season. If you assume that all these perished, the CS survival rate drops to ~13%, the same as the PM colonies.

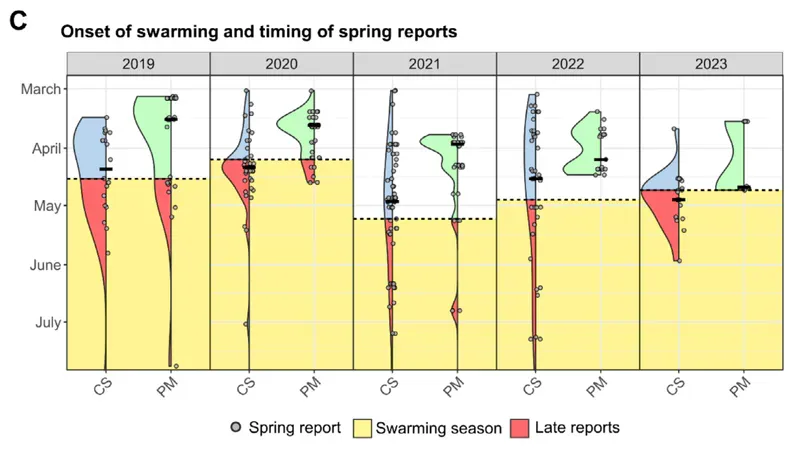

This early season survey occurs at a critical time of the year (March/April).

It was notable that the median date for the first post-winter inspection was the 29th of March for PM nest sites, and over three weeks later (the 21st of April) for CS locations.

This means that a significant number of early season CS reports were unusable, as they post-dated the onset of swarming.

In the figure above, the onset of swarming {{6}} each year is marked by the horizontal dashed line. It differs by up to a month over the 5 years shown. Dots represent the first annual nest site report, shaded blue for CS and green for PM. Clearly a lot of CS reports post-date the onset of swarming.

Questions and conclusions

Germany is a big country, only a little 'shorter' North to South than mainland UK. Whilst Germany probably has slightly less climate variation over this latitude than the UK, I'd be amazed if swarming in Munich (48.1° N) wasn't at least a week or so earlier than Hamburg (53.5° N) {{7}}.

I don't think this regional variation in swarming — assuming it exists — was taken into account when overlaying the time of the first swarm on the CS and PM early season reports.

It probably should be. Think back to the dates I quoted earlier for UK swarming (possibly as early as the end of March this year) and the first swarms I saw in this part of Southern Scotland (10th of May). If my local 'free-living bees' were present in the tree in mid-April this year, I'd be reasonably confident that they had successfully overwintered there. The same would not be true if I lived in the South of England, where swarming likely before then.

Notwithstanding these comments, it's clear that there are significant differences between the results of Citizen Science studies (where there's a bias towards 'positive' reporting i.e. observers are more likely to report live free-living colonies, and less likely to report those that have died/absconded) and direct observation by those running the survey.

Regular readers will know that I've previously expressed some scepticism about the results of overwintering loss surveys. These happen every year, and the results are widely broadcast, yet I'm not aware of any that have been similarly ground-truthed (if that's a real word).

To have real confidence that UK losses — for example — were 35% this year, compared to only 20% last year, you'd need to have direct studies of a representative number of hives by those running the study.

And you would also need some robust statistical analysis.

This sort of thing can be done, and the Rutschmann et al., (2025) study shows why it's important. If beekeepers want to quote 'increased winter losses' (or for that matter, better survival of free-living honey bees) we require good data to back up these claims.

So, there you have it, swarming in Scotland, free-living bees in Germany, data validation, and a new word for you to practice … hoaching.

And the final, AI-generated, take home message? {{8}}

If you're looking for bees … don't just look up 😉

More like this?

That's almost 3,000 words you've just read on bees and beekeeping. If you want more of this every week, then why not sign up as a sponsor of The Apiarist? At least 50% of posts are now for sponsors only, and sponsors ensure that there will be comprehensive, well researched and entertaining posts on sustainable beekeeping appearing every week.

References

Rutschmann, B., Remter, F., and Roth, S. (2025) Monitoring Free-Living Honeybee Colonies in Germany: Insights Into Habitat Preferences, Survival Rates, and Citizen Science Reliability. Ecology and Evolution 15: e71469 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ece3.71469.

{{1}}: I've asked whether the Woodland Trust's Nature's Calendar would be interested in adding swarming to their list of activities recorded.

{{2}}: Or at least 'accessed' … who knows whether it's actually read?

{{3}}: Which won't be happening as I have a life. I'm more than happy to accept that these upticks in 'swarm control' post visits have nothing to do with the start of swarming. However, in the absence of additional evidence, I'm a staunch advocate of Occam's Razor. Prove I'm wrong 😉.

{{4}}: There are always a few drones associated with swarms.

{{5}}: Are holes in trees evenly distributed, or are they influenced — for example — by the prevailing weather, or direction of the sun, or the bias of black woodpeckers, which might help create and enlarge cavities?

{{6}}: Determined from a 'swarm line' and reports to a website.

{{7}}: For comparison, they are 610 km apart, about the same separation as Edinburgh and Plymouth.

{{8}}: Not AI-generated … I doubt ChatGPT could come up with anything so insightful.

Join the discussion ...