Early season inspections

Synopsis : The first inspection of the season needs to be late enough that the colony is expanding well, early enough that it isn’t making swarm preparations and timed to coincide with reasonable weather. Tricky. When you do open the hive you have to deal with whatever you find and leave the colony in a suitable state for the upcoming season.

Introduction

It is often tricky to decide when to do the first inspection of the season.

Too early and the bees will appear disappointingly understrength. If the weather is borderline you risk chilling the brood or the bees may get very defensive.

Or typically, both 🙁 .

Too late and the colonies may have backfilled the comb with early nectar and already started to make swarm preparations.

Twitter has been busy with beekeepers proudly announcing “8 frames of brood” or “Supers on this weekend”, without reference to local conditions or sometimes even their location.

Remember, some of these regular ‘tweeters’ are in France 😉 .

It must be particularly confusing for beekeepers starting their first spring with bees. They are desperate to start ‘real beekeeping’ again, which means opening colonies and looking for queens and brood, just like they were doing at the end of last season {{1}}. However, they get dispirited if the colony is defensive or appears weak (less than 8 frames of brood!), and they kick themselves for not starting sooner if there are queen cells already present.

So what’s the best thing to do?

You have to use your experience and your judgement … or failing those, use some common sense.

I have reasonable amounts of experience and (sometimes) have good judgement, but I mainly rely upon a combination of common sense and local observation {{2}}.

Together with a soupçon of opportunism.

Sometimes my timing is spot on, and sometimes I’m early or a bit late.

In these circumstances you have to deal with whatever you find in the colony and make the best of it.

A false start

Despite the incessant storms and getting trapped in a December blizzard (!) it has been a mild winter. We’ve had an unusually low number of frosts – none in January, one in February and two in March.

I was beginning to think that the season proper was going to start unusually early.

That was reinforced by the weather in the the last fortnight of March, which was fantastic.

Fantastic for March that is {{3}}. Warm days, bees busy with the early season flowering gorse (it flowers all season), even a little nectar being collected.

About half my colonies had received an extra kilo or two of fondant in February or early March, and all received at least one pollen substitute pattie to help get them off to a good start. By late March the colonies were looking good {{4}}.

I’m still a long distance beekeeper, with my colonies about equally split between the east and west coasts of Scotland. I therefore book hotels weeks or months in advance for some of my beekeeping. Predicting the weather that far ahead is impossible, so it involves some guesstimates and, inevitably, some beekeeping in unsuitable weather.

Early season is usually particularly difficult, but by late March this year I was feeling quietly confident {{5}}.

And then April started with several hard frosts and the temperature dropped to single digits (°C) for days at a time.

Still, I was committed to make the trip to Fife … and I’m pleased I went.

And they’re off!

I have a couple of apiaries in Fife. I usually visit both on each of successive days on a trip. That allows me to store all the equipment in one apiary, without having to transport it back and forth across Scotland. This works well and means I can cope with most eventualities.

It was 9°C with a chilly easterly when I got to the first apiary. On removing the lid on the first hive it was very clear that I was (fashionably, of course 😉 ) late to the party … the bees were already building brace comb in the headspace between the top bars of the frame and the underside of the inverted crownboard.

I had no spare equipment with me {{6}}, but it was obvious that the colony needed a queen excluder and a super … as well as quite a bit of tidying up.

Which was going to be the story of the trip.

With infrequent apiary visits – either enforced by distance (in my case) or imposed by bad weather (not unusual in spring) – you have to deal with whatever situations you find when you have the opportunity to open hives.

It was clear from the state of this colony, which was on a single brood box, that the bees had expanded well during the warm weather and were going to rapidly run out of space.

Other colonies in the same apiary were on double brood boxes and were heavy with remaining winter stores – and, no doubt, some early season nectar – and reassuringly packed with bees.

It looked like a very promising start to the season.

More of the same

I travelled on to my main apiary to review the situation there. This is the apiary with my bee shed and all of my stored equipment. It is closer to the coast and the wind blows in directly from the North Sea.

It was colder and even less welcoming.

However, the bees were all in a very good state and clearly needed more space and a little post-winter TLC to get them ready for the season.

However, the temperature precluded any meaningful colony inspections. I could check for laying queens, get an approximation of colony strength (frames of brood) and give them space for further expansion. Anything more than this and there would be a risk of chilling the bees. Because of the low temperature I took relatively few photos.

Interestingly, colonies outside the bee shed were significantly better advanced than those inside. This is the first time I’ve seen this, and I’ve previously commented that the bees in the shed are often a week or two ahead of those outside.

However, in looking back through my notes I think it’s a reflection of the quality and early winter state of the colonies that currently reside in the shed. These are the ones mainly used for research and which regularly have brood ‘stolen’ for experiments (even late into the autumn). Consequently they were probably weaker going into the winter. At least one of the colonies had been united late in 2021 to ensure they would make it through the winter … and they had 🙂 .

What follows is a discussion of a few of the problems (and some potential solutions) that you can encounter at this time of the season.

‘Dead outs’ and ‘basket cases’

I’m not going to dwell on these as there’s not a lot to say and often little that can be salvaged.

Some colonies die overwinter.

I’ve discussed the numbers (and their questionable reliability) before. Most annual surveys show that about 10-35% of colonies die overwinter. The precise percentage depends upon the size and rigour of the survey {{7}}, the severity of the winter {{8}} and the honesty of the beekeepers who respond {{9}}.

Let’s just accept that quite a few colonies are lost overwinter.

I strongly suspect the majority of these losses are due to poor Varroa management. I’ve previously discussed the reasons uncontrolled mite levels are deleterious, and the – relatively straightforward – solutions that can be applied to prevent these losses {{10}}.

It’s always worth conducting a post-mortem on ‘dead outs’ to try and work out what went amiss.

Queen failure

Some queens fail overwinter. This is probably unrelated to poor Varroa control and is ’just another thing that can go wrong’.

They either die, stop laying fertilised eggs or stop laying altogether.

They may or not be present when you check the colony in spring.

Whatever the failure, the overall result is much the same, although the appearance of the colony might differ (in terms of numbers of bees and the proportion of drones present). The colony will be significantly understrength, with little or no worker brood … and may have lots of drones.

I consider colonies with failed queens are a lost cause in March or (at least here in Scotland) much of April.

The bees that remain are likely very old. There’s no use providing them with a frame of eggs in the hope they’ll rear a new queen as it’s unlikely that there are sufficient drones about. If there aren’t flying drones I certainly wouldn’t bother.

You could provide them with a new queen if you can find one, but is it worth it?

The colony will be ‘well behind the curve’ in terms of strength for a month or two. You may have to boost them with additional brood. Unless you have ample spare brood in other colonies (as well as a spare queen and a willingness to commit these resources) I really wouldn’t bother.

Fortunately, at least so far (and I won’t be certain until later this month), all my colonies have survived and are flourishing … so let’s move on to a couple of solvable problems instead.

Brace yourself

When I add a fondant ‘top up’ to a colony I remove the crownboard and place the container of fondant directly over the cluster. This ensures that the bees can immediately access the fondant, rather than negotiating their way through a hole in the crownboard to the cold chilly space under the roof. To provide space for the fondant container I either use an eke or one of my deep-rimmed perspex crownboards.

A consequence of this is that, as the colony expands, they may build brace comb in the headspace over the top bars.

Sometimes they fill the space entirely, though you might be lucky and find they’ve only built inside the fondant container.

Irrespective of the extent of comb building I usually take this to indicate that the colony needs additional space and that they should be supered.

Pronto.

Removing and reusing brace comb

I smoke the bees down – as gently as practical – and cut off the brace comb using a sharp hive tool. In the photos above the comb was filled with early season nectar.

When cutting off the comb I try and prevent too much of the nectar from oozing out and down between the frames. A sharp hive tool held almost parallel to the top bars is often the best solution. Working fast but carefully, I dumped the nectar-filled brace comb into the empty fondant container and then quickly checked the colony. The latter consisted of little more than gently splitting the brood nest and checking the approximate number of frames of brood in all stages.

I added a queen excluder, a super and a crownboard with a small hole in it, above which I placed the salvaged brace comb, surrounded by an empty super.

Finally, I added a second crownboard with some additional honey-filled brace comb they’d built last September. I wrote about this in Winding down last year. The intention is that the bees will take down the nectar/honey above the lower crownboard and either use it for brood rearing (if it’s too cold to forage) or store it properly.

If all this works as hoped the empty comb can be melted down and turned into beeswax wraps.

Waste not, want not 😉 .

The accidental ‘brood and a half’

My colony #7 has a stellar queen who produces prolific, gentle bees and who lays gorgeous slabs of brood with barely a cell missed. I used her as a source of larvae for queen rearing last season and will do so again this year.

The colony entered the winter with a ‘nadired super’. I’ve discussed these somewhere before {{11}}. Essentially this means a stores-filled super underneath the (single in this case) brood box.

Often the bees will empty the super before the winter and it can be safely removed.

Or, as in this instance, completely forgotten 🙁 .

When the bees had emptied it or not is a moot point … by last weekend they’d part filled it again.

With brood.

The queen had moved down into the super and laid up half the frames, at least two of which were drone comb {{12}}.

I consider ‘brood and half’ an abomination. I prefer the flexibility offered by just one size of brood frame and also prefer using a single brood box if possible.

Despite perhaps swearing quietly when I realised the super was half-filled with brood (the drone brood was almost all capped) it’s only really a minor inconvenience.

Furthermore, this is a good queen and is likely to produce drones with good genes. How could I get rid of the ‘brood and a half’ setup as soon as possible and save all those lovely drones with the hope that they could spread their genes far and wide?

Upper entrances

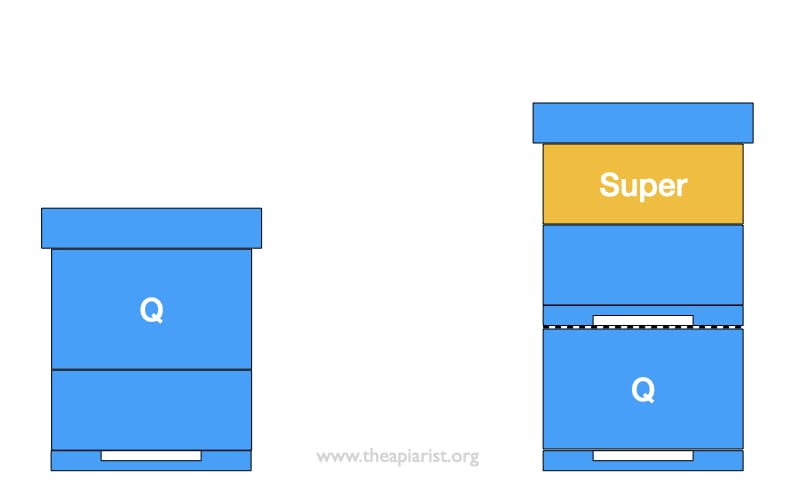

The obvious answer was to add a queen excluder and a super, but to move the nadired super containing brood above the queen excluder.

If there had been no drone brood in this ‘super’ that would have been sufficient. However, drones cannot get through a queen excluder and distressingly {{13}} die trying.

I therefore added an upper entrance to the colony, immediately above the queen excluder. The easiest way to do this is to use a very shallow eke. I build them just 18 mm deep from softwood, with a suitably placed slot only half that depth.

The brood is directly above the brood box and so will be kept warm. The drones can emerge in due course, and fly from the upper entrance. Some will return there but – ‘boys will be boys’ – many will distribute themselves around the apiary waiting for better weather and potential queen mating.

If there is a strong nectar flow the bees can fill the new empty super and they will backfill the no-longer-nadired super once the brood emerges.

And finally … what did I fail to mention in this colony rearrangement ?

That’s right, the thing I failed to mention because I failed to check 🙁 ?

Where was the queen ?

It is important that the queen is in the brood box, rather than the no-longer-nadired super, when you reassemble the hive. If she isn’t, you’ll return to find two supers full of brood and an empty brood box.

A very quick check confirmed that the queen was in the brood box so I left them to get on with things.

Stores

I didn’t do a full inspection on any of the colonies I checked.

It was far too cold to spend much time rummaging around in the boxes. However, I did confirm that all were queenright and had brood in all stages.

I also ‘eyeballed’ the approximate strength of the colonies in terms of frames of brood. Typically this just involves separating the frames and looking down the seams of bees, perhaps partly removing the outer frames only to confirm things. Even just doing this I still saw a few queens which was doubly reassuring 🙂 .

The weakest colonies – those in the shed – had 3-4 frames of brood. The strongest were booming … perhaps even the 8 cadres de couvée {{14}} you read about on Twitter 😉 .

All of the colonies had ample stores, and several had too much.

The capped frames of stores were occupying valuable space in the brood box that the colony will need to expand into over the next 2-3 weeks. I therefore used my judgement to replace one or two frames {{15}} of capped stores with drawn comb or new frames. I save the frames of stores carefully and will use them to make up nucs next month.

I’ve heard mixed reports of winter survival and spring build up this year. I’m aware that some beekeepers in the south of England are reporting higher than usual colony losses. Others were reporting very strong expansion in the early spring and even a few early swarms.

It will be interesting to see how the season develops. As always it will be ’the same, but different’ which is one of the things that makes beekeeping so challenging and enjoyable.

{{1}}: Reality check … ‘real beekeeping’ also means running a smelly steam wax extractor in the rain in November or making frames in January when it’s too cold to feel your fingertips.

{{2}}: I’ve been meaning to write a post about phenology – studying the cyclic and seasonal natural phenomena e.g. the arrival of cuckoos, the flowering of willow – but it’s not progressed further than a rough draft so far. Cuckoos will typically arrive here in about 10 days, wheatear by the weekend and chiffchaff are overdue.

{{3}}: Remember this is Scotland … actually, thinking about it, the weather we had in late March was fantastic for some July’s.

{{4}}: As determined by observing their activity and peeking through the perspex crownboard. I’d not opened any boxes, other than to add fondant and patties.

{{5}}: Will I ever learn?

{{6}}: This was effectively my out apiary.

{{7}}: The more the better.

{{8}}: The excuse most beekeepers use for lost colonies, despite the overwhelming evidence that Varroa is probably the main culprit.

{{9}}: Always unquestionable, of course.

{{10}}: And I’m not going to repeat things here …

{{11}}: For example, here if you care to look.

{{12}}: I use a lot of drone foundation in my supers.

{{13}}: To me at least.

{{14}}: With thanks to Google Translate and apologies to French readers.

{{15}}: In the case of those on a double brood box.

Join the discussion ...