Midseason mite management

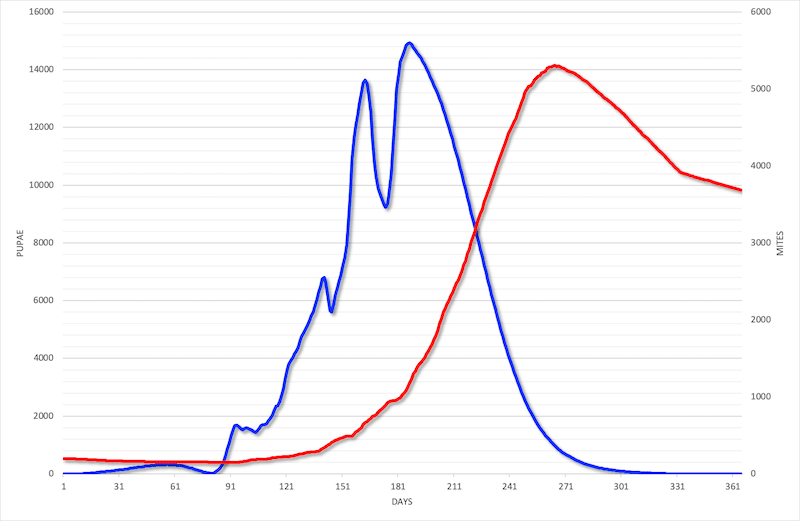

The Varroa mite and the potpourri of viruses it transmits are probably the greatest threat to our bees. The number of mites in the colony increases during the spring and summer, feeding and breeding on sealed brood.

In early/mid autumn mite levels reach their peak as the laying rate of the queen decreases. Consequently the number of mites per pupa increases significantly. The bees that are reared at this time of year are the overwintering workers, physiologically-adapted to get the colony through the winter.

The protection of these developing overwintering bees is critical and explains why an early autumn application of a suitable miticide is recommended … or usually essential.

And, although this might appear illogical, if you treat early enough to protect the winter bees you should also treat during a broodless period in midwinter. This is necessary because mite replication goes on into the autumn (while the colony continues to rear brood). If you omit the winter treatment the colony starts with a higher mite load the following season.

And you know what mites mean …

Mites in midseason

Under certain circumstances mite levels can increase to dangerous levels {{1}} much earlier in the season than shown in the graph above.

What circumstances?

I can think of two major reasons {{2}}. Firstly, if the colony starts the season with higher than desirable mite levels (this is why you treat midwinter). Secondly, if the mites are acquired by the colony from other colonies i.e. by infested bees drifting between colonies or by your bees robbing a mite infested colony.

Don’t underestimate the impact these events can have on mite levels. A strong colony robbing out a weak, heavily infested, collapsing colony can acquire dozens of mites a day.

The robbed colony may not be in your apiary. It could be a mile away across the fields in an apiary owned by a treatment-free {{3}} aficionado or from a pathogen-rich feral colony in the church tower.

How do you identify midseason mite problems?

You need to monitor mite levels, actively and/or passively. The latter includes periodic counts of mites that fall through an open mesh floor onto a Varroa board. The National Bee Unit had a handy – though not necessarily accurate – natural drop calculator to determine the total mite levels in the colony based on the Varroa drop (it disappeared in their website re-shuffle recently).

Don’t rely on the NBU calculator. A host of factors are likely to influence the natural Varroa drop. For example, if the laying rate of the queen is decreasing because there’s no nectar coming in there will be fewer larvae at the right stage to parasitise … consequently the natural drop (which originates from phoretic mites) will increase.

And vice versa.

Active monitoring includes uncapping drone brood or doing a sugar roll or alcohol wash to dislodge phoretic mites.

Overt disease

But in addition to looking for mites you should also keep a close eye on workers during routine inspections. If you see bees showing obvious signs of deformed wing virus (DWV) symptoms then you need to intervene to reduce mite levels.

During our studies of DWV we have placed mite-free {{4}} colonies into a communal apiary. Infested drone cells were identified during routine uncapping within 2 weeks of our colony being introduced. Even more striking, symptomatic workers could be seen in the colony within 11 weeks.

Treatment options

Midseason mite management is more problematic than the late summer/early autumn and midwinter treatments.

Firstly, the colony will (or should) have good levels of sealed brood.

Secondly, there might be a nectar flow on and the colony is hopefully laden with supers.

The combination of these two factors is the issue.

If there is brood in the colony the majority (up to 90%) of mites will be hiding under the protective cappings feasting on sealed pupae.

Of course, exactly the same situation prevails in late summer/early autumn. This is why the majority of approved treatments – Apistan (don’t), Apivar, Apiguard etc. – need to be used for at least 4-6 weeks. This covers multiple brood cycles, so ensuring that the capped Varroa are released and (hopefully) slaughtered.

Which brings us to the second problem. All of those named treatments should not be used when there is a flow on or when there are supers on the hive. This is to avoid tainting (contaminating) the honey.

And, if you think about it, there’s unlikely to be a 4-6 week window between early May and late August during which there is not a nectar flow.

MAQS

The only high-efficacy miticide approved for use when supers are present is MAQS {{5}}.

The active ingredient in MAQS is formic acid which is the only miticide capable of penetrating the cappings to kill Varroa in sealed brood {{6}}. Because MAQS penetrates the cappings the treatment window is only 7 days long.

I have not used MAQS and so cannot comment on its use. The reason I’ve not used it is because of the problems many beekeepers have reported with queen losses or increased bee mortality. The Veterinary Medicines Directorate MAQS Summary of the product characteristics provides advice on how to avoid these problems.

Kill and cure isn’t the option I choose 😉 {{7}}

Of course, many beekeepers have used MAQS without problems.

So, what other strategies are available?

Oxalic acid Api-Bioxal

Many beekeepers these days – if you read the online forums – would recommend oxalic acid {{8}}.

I’ve already discussed the oxalic acid-containing treatments extensively.

Importantly, these treatments only target phoretic mites, not those within capped cells.

Trickled oxalic acid is toxic to unsealed brood and so is a poor choice for a brood-rearing colony.

In contrast, sublimated (vaporised) oxalic acid is tolerated well by the colony and does not harm open brood. Thomas Radetzki demonstrated it continued to be effective for about a week after administration, presumably due to its deposition on all internal surfaces of the hive. My daily mite counts of treated colonies support this conclusion.

Consequently beekeepers have empirically developed methods to treat brooding colonies multiple times with vaporised oxalic acid Api-Bioxal to kill mites released from capped cells.

The first method I’m aware of published for this was by Hivemaker on the Beekeeping Forum. There may well be earlier reports. Hivemaker recommended three or four doses at five day intervals if there is brood present.

This works well {{9}} but is it compatible with supers on the hive and a honey flow?

What do you mean by compatible?

The VMD Api-Bioxal Summary of product characteristics {{10}} specifically states “Don’t treat hives with super in position or during honey flow”.

That is about as definitive as possible.

Some vapoholics (correctly) would argue that honey naturally contains oxalic acid. Untreated honey contains variable amounts of oxalic acid; 8-119 mg/kg in one study {{11}} or up to 400 mg/kg in a large sample of Italian honeys according to Franco Mutinelli {{12}}.

It should be noted that these levels are significantly less than many vegetables (or rhubarb leaves).

In addition, Thomas Radetzki demonstrated that oxalic acid levels in spring honey from OA vaporised colonies (the previous autumn) were not different from those in untreated colonies.

Therefore surely it’s OK to treat when the supers are present?

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence

There are a few additional studies that have shown no marked rise in OA concentrations in honey post treatment. One of the problems with these studies is that the delay between treatment and honey testing is not clear and is often not stated {{13}}.

Consider what the minimum potential delay between treatment and honey harvesting would be if it were allowed or recommended.

One day {{14}}.

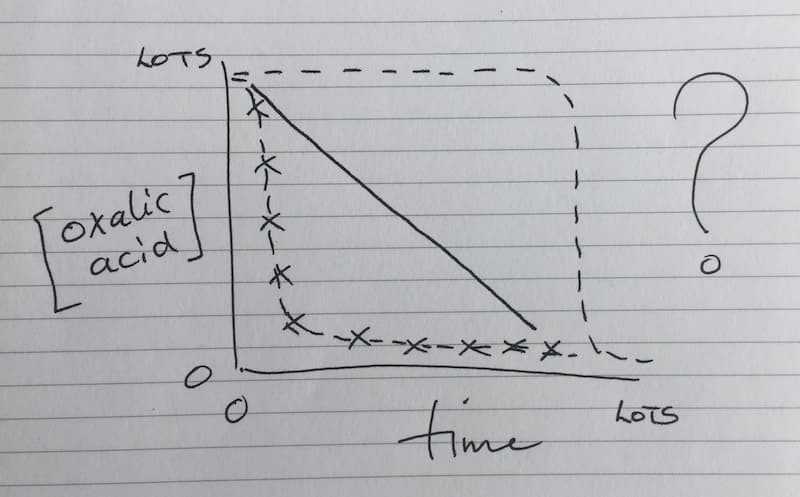

No one has (yet) tested OA concentrations in honey immediately following treatment, or the (presumable) decline in OA levels in the days, weeks and months after treatment. Is it linear over time? Does it flatline and then drop precipitously or does it drop precipitously and then remain at a very low (background) level?

How does temperature influence this? What about colony strength and activity?

Frankly, without this information we’re just guessing.

Why risk it?

I try and produce the very best quality honey possible for friends, family and customers.

The last thing I would want to risk is inadvertently producing OA-contaminated honey.

Do I know what this tastes like? {{15}}

No, and I’d prefer not to find out.

Formic acid and thymol have been shown to taint honey and my contention is that thorough studies to properly test this have yet to be conducted for oxalic acid.

Until they are – and unless they are statistically compelling – I will not treat colonies with supers present … and I think those that recommend you do are unwise.

What are the options?

Other than MAQS there are no treatments suitable for use when the honey supers are on. If there’s a good nectar flow and a mite-infested colony you have to make a judgement call.

Will the colony be seriously damaged if you delay treatment further?

Quite possibly.

Which is more valuable {{16}}, the honey or the bees?

One option is to treat, hopefully save the colony and feed the honey back to the bees for winter (nothing wrong with this approach … make sure you label the supers clearly!).

Another approach might be to clear then remove the supers to another colony, then treat the original one.

However, if you choose to delay treatment consider the other colonies in your own or neighbouring apiaries. They are at risk as well.

Finally, prevention is better than cure. Timely application of an effective treatment in late summer and midwinter should be sufficient, particularly if all colonies in a geographic area are coordinately treated to minimise the impact of robbing and drifting.

I’ve got two more articles planned on midseason mite management for when the colony is broodless, or can be engineered to be broodless {{17}}.

{{1}}: Which, for convenience, we’ll define as the 1000 mite limit/colony suggested by the National Bee Unit.

{{2}}: In addiition, mite numbers will be influenced by the laying rate of the queen, the available pupae and the proportion of drone brood in the colony.

{{3}}: A leave and let die beekeeper.

{{4}}: Formally we cannot prove these were mite-free but they originated in an apiary with very tightly managed mite levels in which an early autumn drop – during treatment – of 20-30 mites in total was considered high.

{{5}}: Mite Away Quick Strips

{{6}}: Fries I. (1991). Treatment of sealed honey bee brood with formic acid for control of Varroa jacobsoni. American Bee Journal, 131, 313–314.

{{7}}: I’ve also not used MAQS because I rarely see worryingly high midseason mite levels.

{{8}}: And a few would suggest rhubarb leaves.

{{9}}: I’ve used this many times as my sole Varroa control method in late summer.

{{10}}: Of course, oxalic acid comes with no instructions and is not an approved treatment so there’s no documentation to consult … but the active ingredient is exactly the same so you can assume that the same applies to oxalic acid.

{{12}}: F. Mutinelli et al., (1997) L’acido ossalico nella lotta alla varroasi, L’ape 4/1997, Istituto Zooprofilattico, Legnaro, Italy … I’ll admit to not being able to read this in the original Italian.

{{13}}: The Enzo et al., 2004 (PDF) study sometimes quoted could be interpreted as having treatment and testing at least 6-8 weeks apart. However, it is not specifically stated and the authors are rather vague in the paper …

{{14}}: You have to exclude common sense when drawing up rules … if it were allowed/recommended it is inevitable that some would treat very close to the time the supers were cleared for extraction (3 to 4 treatments at 5 day intervals takes 15-20 days).

{{15}}: And are my taste buds – dulled by years of strong curry, red wine and fine cigars – sufficiently sensitive to detect any off flavours anyway?

{{16}}: This is perhaps an ethical and financial decision. Just because they are insects does not mean they should not be managed in the best way we possibly can.

{{17}}: But they won’t necessarily appear in the next two weeks as I need time to prepare some more high quality graphs like the one above …

Join the discussion ...