OA Q&A

The post last week on the preparation of oxalic acid (OA; the active ingredient in the commercially available and VMD approved product Api-Bioxal) generated a slew questions. Inevitably, some of these drifted off topic … at least as far as the specific content of the post was concerned.

This partly reflects the deficiency of a weekly blog as a means of communicating.

It may also reflect the inadequacy of the indexing system {{1}}.

Comprehensive coverage of subject, and peripherally related topics, would require a post so long that most readers {{2}} would give up halfway through.

And it would take so long to write that the weekly post format would have to be abandoned.

The resulting magnum opus would be a masterpiece of bad punctuation, littered with poor puns and would leave me nothing to write the following week …

This week I’ve attempted to address a series of oxalic acid-related points that should have been mentioned before, that I’ve received questions about, or I think justify a question (and answer).

Should I trickle treat or vaporise?

One of the key features of approved miticides is that, used according to the instructions and at the appropriate time, they are very effective.

Conversely, use them incorrectly or at the wrong time and they will be, at best, pretty hopeless.

In the case of OA, both trickle treating (dribbling) or vaporisation (sublimation) can achieve 90% or more reduction in the levels of phoretic mites.

Therefore, the choice between them is not on the grounds of efficacy but should be on their ease of us, convenience, safety or other factors.

Trickle treating is fast, requires a minimum amount of specialised equipment and only limited PPE (personal protection equipment).

I’d strongly recommend using a Trickle 2 bottle from Thorne’s to administer the solution. It is infinitely better than a syringe, which requires the use of at least two hands.

If you hold the crownboard up at an angle with one hand you can administer the OA solution using the other. Wear gloves and your bee suit. It takes as long to read as it does to do.

With a Trickle 2 bottle and some pre-warmed OA-containing solution it should be possible to open, treat and close a colony in well under two minutes. Like this …

On a cold day very few bees will be disturbed. The OA will dribble down through the clustered colony and the mites will get what they deserve 🙂

Temperature and treatment choice

It’s usually the temperature that determines whether I trickle or vaporise. I prefer to trickle when the colony is clustered, but would usually treat by sublimation on a warmer day.

At what temperature does cold become warm? About 8-9°C … i.e. about the temperature at which the bees start to cluster.

Partly this is to reduce the number of bees that might be disturbed – I can vaporise a colony without opening the box.

However, my crashingly unscientific opinion – based entirely on gut feeling and guesswork {{3}} – is that the OA vapour perfuses through loose clusters better, whereas the solution is more likely to come into contact with the mites when dribbling down through the cluster.

I have no data to support this – don’t say you weren’t warned!

Through choice I’d not treat (unless I had to) if the temperature was much below 3-4°C. The bees get rapidly chilled should something goes wrong – you drop the bottle, get a bee in your veil or whatever.

Of course, if you haven’t got a vaporiser your choice is limited to trickle treating. Likewise, if you don’t enjoy scouring caramelised glucose from the pan of your vaporiser you should probably stick to trickling Api-Bioxal solution.

The only additional thing to consider is whether there’s brood present in the hive – I discuss this in more detail below.

How can I use a vaporiser and an Abelo poly floor?

I use a lot of Abelo poly hives. Mine are all the ‘old design‘ with the floor that features a long landing board and an ill-fitting Varroa tray. The new ones don’t look fundamentally different from the website {{4}}.

My storage shed has a shoulder-high stack of unused Abelo floors as I prefer my own homemade ‘kewl’ floors.

However, inevitably some Abelo floors get pressed into use during the season and – through idleness, disorganisation and a global virus pandemic – remain in use during the winter 🙁

I’ve now worked out how to vaporise colonies using these floors. Please remember, my vaporiser is a Sublimox which has a brass (?) nozzle through which the vapour is expelled. The nozzle gets very hot and melts polystyrene.

Don’t ask me how I know 🙁

The underside of the open mesh floor can be sealed by inverting the Varroa tray and wedging a block of foam underneath at the back. I didn’t think this would work until I tried it, and was pleasantly impressed.

This is important as it significantly reduces the loss of OA vapour. Any vapour that escapes is OA that will not be killing mites.

The Sublimox can be simultaneously inserted and inverted through the front entrance. This takes some deft ‘wrist action’ but results in minimal loss of OA vapour.

To protect the poly I use a piece of cardboard. You simply rest the nozzle on this.

As soon as the vaporiser is removed the bees will start to come out, so use the cardboard to block the entrance for a few minutes, by which time they will have settled.

The gaffer tape in the photo above is sealing the ventilation holes in the entrance block, again keeping valuable OA vapour inside the hive.

And on a related point …

My favoured nuc is the Everynuc. This is a Langstroth-sized box with a removable floor and an integral feeder that more-or-less converts the box to take National frames. It’s well-insulated, robust, easy to paint and – in my view – a more flexible design that the all-in-one single moulded boxes (like the offering from Maisemores).

However, the entrance of the Everynuc is too big.

The disadvantage of this is that a DIY entrance reducer is needed if the nuc is weak and at risk from robbing.

Conversely, the large entrance and short (~2cm) “landing board” is preferable during OA vaporisation. I carry a nuc-width strip of wood, 2 cm thick, with a central 7 mm hole.

With this balanced on the landing board, the vaporiser can be inserted and inverted without loss of vapour or risk of melting the poly. It’s a quick and dirty fix that I discovered several years ago and have never got round to improving.

How do I know if the colony is broodless?

Oxalic acid is a single-use treatment, remaining active in the hive for significantly less time than a brood cycle (see mite counts below). Therefore, the ‘appropriate time’ to use it is when the colony is broodless.

An additional consideration is that open brood is very sensitive and responds unfavourably to a warm acid bath in OA i.e. it dies {{5}}.

In contrast, sealed brood is impervious to OA vapour or solution.

So, how can you tell if the colony is broodless or not?

The easiest way to determine whether the colony has sealed brood is – on a slightly better day – to open the box and have a look.

Done quickly and calmly I suspect this is more distressing for the beekeeper than it is for the colony. You think the bees will be aggressive or distressed. In reality they’re usually pretty lethargic and often very few fly at all.

You only need to look at the frame in the centre of the cluster. If there’s brood present it will be where the bees are most concentrated. You will probably well see the queen nearby.

Gently, gently, quicky peeky

Remove the roof and insulation and lift one corner of the crownboard. Give them a gentle puff of smoke under the crownboard {{6}}. Wait 30 seconds or so and gently remove the crownboard.

There will be bees on the underside of the crownboard. Stand it carefully to the side out of the breeze. The bees will probably crawl to the upper edge, remember to shake them off into the hive rather than crush them when you place it back on the hive.

The colony is likely to be clustered if the weather is 8°C or cooler. Remove the outer frame furthest from the cluster. If it’s late autumn or early winter this should still be heavy with stores. Here’s one I pulled out last week.

Now you have space to work. Viewed from above the cluster will often be spread over several frames and shaped approximately like a rugby ball.

In the hive shown above they occupied the front five seams {{7}} with a few stragglers between frames 6 and 7.

I used my hive tool between frames 3 and 4 to split the colony, just levering them a centimetre or so apart, so I could then separate frame 3 from 2 and lift it out.

The queen was on the far side of frame 3.

It looks like magic to inexperienced beekeepers, but it really isn’t …

The top of the frame was filled with sealed stores, the lower part of the frame was almost full of uncapped stores.

There was no sealed brood and no eggs or larvae that I could see {{8}}. An adjacent hive looked very similar. Again, the queen was on the reverse side of the first frame I checked. The bees were barely disturbed. Almost none flew and the boxes were carefully sealed up again.

No brood, so ready to treat 🙂

Can I determine if there’s brood present without opening the hive?

Possibly.

You should be able to tell if brood is emerging by the appearance of the characteristic biscuit-coloured wax crumbs on the Varroa tray.

Think digestive rather than Fox’s Party Rings

To see this evidence you need to start with a clean Varroa tray. In addition, the underside of the open mesh floor must be sufficiently draught-free that the cappings aren’t blown around, or accessible to slugs.

Remember that there might be only a very small amount of brood emerging. They may also be uncapping stores (which will have much paler cappings).

Leave the tray in place for a few days and check for darker stripes of crumbs/cappings under the centre of the cluster.

Note that the photograph above was taken in mid-February. A late autumn colony would almost certainly have significantly less brood cappings present on the tray. The brood cappings are the two and a bit distinct horizontal stripes concentrated just above centre. The stores cappings are the white crumbs forming the just discernible stripes the full width of the tray.

You cannot use this method to infer anything about whether there’s unsealed brood present. At least, not with any certainty. If, in successive weeks, the amount of brood cappings increases there’s almost certainly unsealed brood present. Conversely, if brood cappings are reducing there may not be unsealed brood if the queen is just shutting down.

While you’re staring at the tray …

Look for Varroa.

It’s useful to have an idea of the mite drop in the few days before OA treatment.

If it’s high then treatment is clearly needed.

If it’s low (1-2 per day) you have a useful baseline to compare the number that fall after treatment.

You may well be surprised (or perhaps disappointed) at the number that appear from a colony that has already had an autumn treatment.

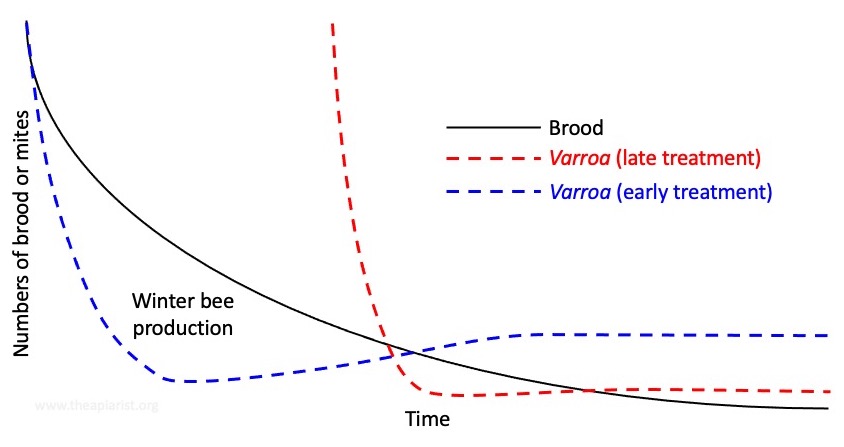

It’s worth remembering that {{9}} there will be more mites present in the winter if you treated early enough in the autumn to protect the winter bees (blue line).

Conversely, if you get little or no mite drop with an OA treatment in the winter it indicates the bees have not been rearing brood in the intervening period. That means the diutinus winter bees were reared before or during the last treatment, meaning they will have been exposed to high mite levels (red line).

This is not a good thing™.

In my experience the daily mite drop is highest 24-48 hours after treatment. I usually try and monitor it over 5-7 days by which time the drop has reached a basal level, presumably because the OA has disappeared or stopped being effective.

Finally, the ambient temperature has an influence on the Varroa drop. I’ll write about this sometime in the future, but it’s worth looking out for.

{{1}}: Which actually isn’t too bad … use the search facility at the top of the page. It finds stuff in titles, in tags and in post texts. Alternatively, the menu bar has lots of relevant stuff under various semi-logical subheadings.

{{2}}: Or this writer.

{{3}}: No evidence, no side-by-side comparisons, no placebo-controlled randomised double blind trials, nothing, nada!

{{4}}: Do any readers know whether they are compatible?

{{5}}: It appears not to be harmed by vaporised OA, in studies from the University of Sussex.

{{6}}: Not through the entrance … you want to push the bees down rather than up.

{{7}}: Six, if you also count the one against the front wall of the hive. In poly hives the bees often rear brood in these outer frames which is something that rarely happens in cedar boxes, other than at the peak of the season.

{{8}}: Mid-afternoon, mid-November, murky light and my eyes!

{{9}}: Assuming your autumn treatment actually worked.

Join the discussion ...