Site and smell

Synopsis : Where should bait hives be located to capture your own lost swarms? {{1}} Can you omit the old brood frame and still make the bait hive attractive?

Introduction

Social media can be seriously misleading for beekeepers. For months now it seems like I’ve been reading about boxes bulging with bees, third supers being added, swarms swarming and the oil seed rape bonanza.

For a beginner living anywhere north of Watford {{2}} this must be a major distraction.

Is the season passing them by?

Perhaps there’s something wrong with their bees?

With luck they’ve resisted the temptation to go rummaging through the brood box. Twice, because they didn’t see the queen on the first run through. Or the second. Should they buy another queen ’just in case’? {{3}}

Old lags, by contrast, give a resigned shrug knowing that the season will be along in due course.

In its own good time … {{4}}.

There’s nothing to be gained by trying to force things. Why open the box, why search for the queen, why risk chilling the bees and brood? There’s pollen going in on the few days good enough for flying, the water carriers are water carrying, the hive has stores (or you’ve quickly added a kilo or two of fondant under the crownboard) and things are progressing much as they should be … though definitely not in lockstep with events reported by the Twitterati in warmer climes.

But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to do.

And, for me, mid-April means it’s time to prepare a bait hive or three in the hope of attracting a few errant swarms.

Under the roof

Over the past seven years I’ve kept bees in Scotland I’ve yet to see a swarm before mid/late April. I’m sure they occur, but they are either in very sheltered regions, or I’m not observant enough to notice them {{5}}.

A bivouacked swarm

However, the visible loss of a swarm is preceded by lots of activity under the hive roof; it’s usually become very overcrowded, the consequent dilution of queen mandibular and footprint pheromones results in the production of swarm cells, the chosen larvae are fed heavily and the cells capped on the 8th day … when, weather permitting, the colony swarms.

With regular inspections you can avoid losing the bees by employing a variety of swarm control methods (all of which – at least all of the effective ones 😉 – are based on well established principles). Overcrowded hives are given more space (more correctly swarm prevention, not swarm control) but the appearance of queen cells means prompt action is needed.

Applied correctly and in a timely manner, swarm control is almost foolproof.

Unfortunately for beekeepers – except for those of us who like ‘freebees’ – too often the swarm control is missed altogether, is applied too late or is used incorrectly.

As a consequence, a lot of swarms are lost.

There are other, less noticeable, things going on with the hive as it makes swarm preparations.

One of these is the surveying of the environment by the aptly names scout bees. These bees are looking for likely new nesting sites that the swarm could occupy.

Scout bees

I give a lot of talks over the winter, one of which is on swarming and bait hives. Last December I delivered this talk to the Scottish Native Honey Bee Society. The audience included Thomas Seeley who has conducted some of the most detailed and elegant studies of swarming in honey bees (described in his book Honeybee Democracy) {{6}}.

In the majority of studies of swarming and nest site selection, scientists prepare an ‘artificial swarm’ by shaking the queen and workers into a box and feeding them lashings of syrup. This ’swarm’ can then be placed on a post, recapitulating a naturally bivouacked swarm, and the scout bee activity is then easily observed.

It should be noted in passing that this type of ‘artificial swarm’ is not the same as the type a beekeeper would use for swarm control {{7}}.

During the Q&A I was asked why bees bivouac; do they sometimes leave the original nest site and fly directly to the new site?

My answer went something like:

I’ve always thought that the bivouac provided an uncluttered dance floor on which the scouts could tango, without interruption or interference from returning workers doing their rhumba- or salsa-flavoured reports of good forage in the vicinity.

However, Thomas Seeley indicated that he had (very rarely) observed swarms leaving a hive and not bivouacking, but instead going directly to a new nest site.

This clearly isn’t the way things usually happen, but the very fact it does happen tells us something about scout bee activity and nest site selection.

The timing of scouting and swarming

Since it is the scout bees that ‘lead’ the swarm they must know where they’re going.

This, in turn, means that scout bees must be exploring the environment and deciding on the best nest site before the colony swarms. This decision making process involves returning scouts dancing to persuade other scout bees to check out potential nest sites, finally resulting in a quorum-based choice of the ‘best’ nest site.

Swarm moving into a bait hive …

So this reporting/persuasion ‘feedback loop’ by the scout bees is another thing going on ‘under the roof’ as the colony makes swarm preparations.

My own strictly amateur observations suggest that scout bee activity is sometimes detectable at least one to two weeks before swarming occurs {{8}}.

How long in advance of swarming are scout bees active? No more than a fortnight, or much longer?

I don’t know.

I suspect the answer is not straightforward. Scout bees are ‘middle aged’ bees transitioning from hive duties to foragers. It may well be that there’s a low level of scout bee activity going on all the time, albeit inextricably intertwined with orientation and initial foraging flights.

Is this activity sufficient to reach a decision and lead a swarm to a new nest site without bivouacking?

Probably not, after all most swarms bivouac. However, perhaps there are circumstances where swarming is delayed (bad weather, insufficient young bees, overweight queen?) so allowing the scouts more time to make the decision inside the hive?

Des res

I also expect the timing of these decisions is impacted by the number and desirability of nest sites in the area. If there are a large number of suitable sites I would expect the decision-making process to take more time.

In contrast, in an environment short of suitable nest sites I would expect that the quorum decision would take less time … perhaps so little time that the choice is made before the colony actually swarms.

Many swarms bivouac for hours or days; Seeley recounts (in Honeybee Democracy) studies by Martin Lindauer where swarms were bivouacked for 4-5 days before relocating. In some cases this was clearly due to adverse weather, but perhaps others were due to too much choice?

Bait hives

Anyway, enough thinking aloud … whatever the timing of scout bee activity, I’ve always reasoned that a well-sited bait hive, regularly watched for scout bee activity, provides a useful early warning system for swarming.

If you see scout bees showing increasing interest in your bait hive go and check your hives in the area. Are there any open queen cells present? {{9}}

I’ve written about bait hives in several previous posts and I don’t intend to rehash the subject again, other than to say the scout bees are looking for:

- a 40 litre void

- smelling of bees

- with a small entrance situated near the bottom of the void

- facing south

- shaded but clearly visible

- and located at least 5 metres above the ground

Remember, these are the optimum features determined through years of painstaking research.

Incoming!

They are not the absolute requirements. If the entrance faces west, or the void is 50 litres, or it’s at knee height, it may well still be selected. I’d encourage you to read Bait hives evolution and compromise which discusses varying some of the features through necessity or preference.

For the rest of this post I’m going to discuss only one thing on the list above, and one thing missing from the list altogether.

Let’s deal with the omission first.

Siting bait hives to catch your own bees

One of the questions most frequently asked after my bait hive talk goes something like this:

Where should I site a bait hive to capture a swarm from one of my own hives? Can I put the bait hive in the apiary?

Ah ha! Someone lacking confidence in their swarm prevention and control 😉 .

As the saying goes, ’A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’. Far better to not lose the swarm in the first place than rely on ‘recapturing’ it with a tempting-looking bait hive. Polish up your understanding of how and why swarm control works … or try the easiest method of all.

But it’s still a valid question.

And it turns out that Martin Lindauer and Thomas Seeley have both done research that help answer this question. Of course, they didn’t address that specific question, but instead asked:

How far do swarms travel?

At its most simple this involves preparing an ‘artificial swarm’ (as described above), following it to its final destination and measuring the linear distance travelled.

However, this isn’t as easy as it sounds. A swarm moves at about 6 km/h (4 mph) over the ground and some travel many miles from their starting point. Following them – over fences, ditches, through woods, across fields etc. – is nearly impossible {{10}}.

But is there another way?

I see you baby {{11}}

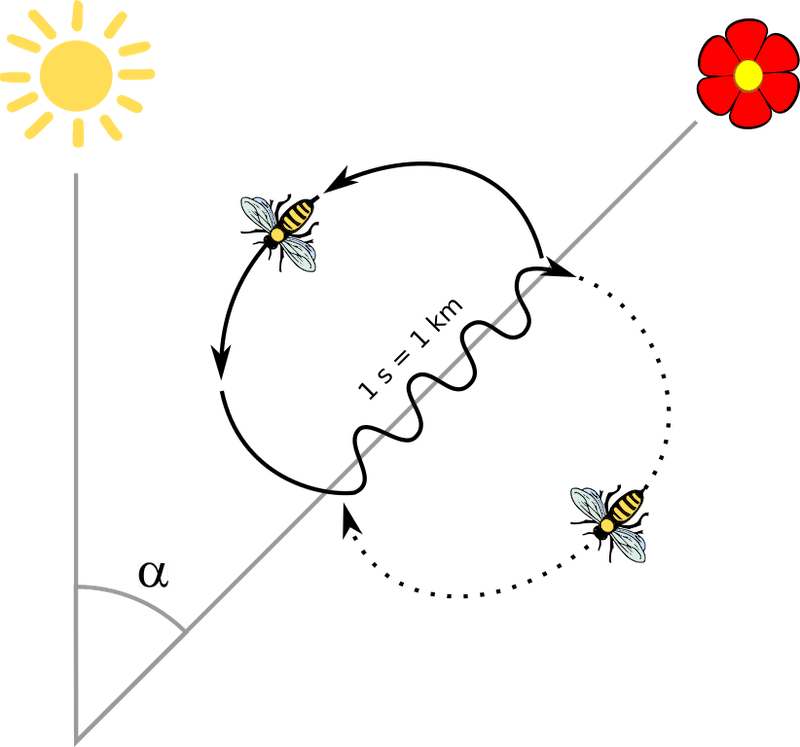

There is … the scout bees communicate the distance, direction and quality of potential nest sites using the waggle dance. Therefore, with close observation, you can infer the distance travelled by recording the duration of the waggle phase of the dance, where 1 second is equal to about 1 km.

The waggle dance

You can’t just watch any scout bee, you have to estimate the location indicated by the majority of the scouts shortly before the swarm takes off {{12}}.

There’s an added complication. Although the distance to the chosen nest site is a fixed measurement (300 metres, 2.5 km), the complexity of the intervening ‘scenery’ influences the optic flow by which bees judge the distance. I’ve discussed Esch and Burns optic flow hypothesis in a previous post on distance measurements by bees, so won’t go into the gory details again here.

Therefore, although 1 second is about 1 km, accurate calibration of the waggle dance is needed to be certain; I’m not aware that this has been done with studies of swarm relocation.

What this means is that – certainly for the longer distances, say > 1 km – you should assume the distance measurements are approximate, perhaps only to 50-100 metres accuracy.

It’s a bit of a moot point anyway as the question was whether a bait hive located within the apiary would capture a lost swarm from that apiary.

And the answer is …

Probably not … the bait hive needs to be located at least 300 metres away.

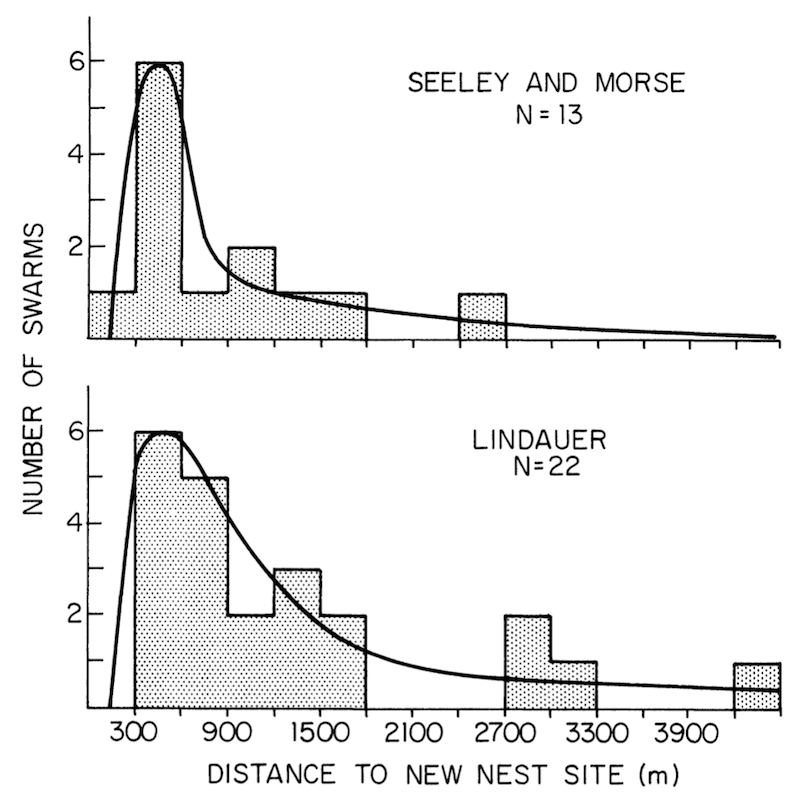

Studies conducted almost 5 decades apart by Martin Lindauer and Thomas Seeley produced remarkably similar results. Each watched a number of swarms relocating and then recorded the distance they travelled – either by direct observation, or inference from the waggle dance.

Most swarms only travel a short distance to a new nest site

Of the 35 swarms observed, only one travelled less than 300 metres. However, 30 swarms travelled less than 1.5 km and the distribution was strongly skewed towards shorter distances.

Further studies by other scientists have shown that ~50% of swarms travel no further than about 1 km.

Therefore, a bait hive situated within your apiary is unlikely to attract a swarm that emerges from a hive in the same apiary.

But that doesn’t mean that it’s unlikely to catch a swarm … 😉 .

I almost always set a bait hive up in the corner of my apiaries, usually off to one side, or tucked away at the back rather than right next to an occupied hive. Now and again I attract a swarm … they’re not my most successful bait hives, but ’A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’ … or the church tower, school roof or loft space.

I’m going to leave speculating about why swarms generally move short distances to ‘another time, another place’ … it’s interesting.

Passing the smell test

Scout bees prefer potential nest sites that smell as though they have previously been occupied by bees.

This has also always interested me. If a nest site smells of bees, but is currently unoccupied, it means that the bees have died out (unless they absconded, and for various reasons I think absconding is unlikely in temperate regions from voluntarily occupied locations). If they’ve died it means they succumbed to disease, or starved because the forage was poor in the area, or because the nest was robbed by a bear {{13}} etc.

Surely there are better locations?

But, on the plus side, one of the reasons the potential nest site smells of bees is because it contains old comb, or because the walls are coated with propolis. The former might save the swarm effort building new comb, and the latter likely still retains antibacterial activity.

Old brood frame and foundationless frames

Whatever the pros and cons of previously occupied sites, the preference of scout bees for nest sites that smell of bees is well documented. The usual advice when preparing bait hives is therefore to include a single old, dark brood frame (no stores!), pushed up against the side wall.

Indeed, not only is this the usual advice, it’s also what I’ve been doing for the last decade and a bit. And, of course, it works. The swarm moves in and clusters on this brood frame. The queen, assuming it’s a prime swarm, starts laying up the frame within hours of the swarm arriving.

At some point in the future I have to remember to remove that old brood frame and replace it with something a little less tired.

But that might not be until the following season … 🙁 .

The same, but different

If the bait hive is not occupied the old brood frame can become a magnet for wax moths. Is there another way the smell of bees can be provided without inclusion of an old brood frame?

Of course there is.

Extracted wax (and the rest)

In the same SNHBS talk on bait hives I was asked by John Durkacz of Fife Beekeepers whether I’d tried painting the inside of the bait hive with wax and/or propolis. It wasn’t clear from John’s question whether he had, but the potential benefits were immediately obvious:

- one fewer thing to procure when setting out bait hives (I’ve had one or two years when every old brood frame contained either stores or loads of pollen, neither of which I want in my bait hives)

- no old brood frame to replace or forget

- no reduction of the bait hive void volume by ~1/11th (though I’d be astounded if the bees could measure this difference)

So I’m giving it a go this season.

One slo cooker = marital strife, two slo cookers = happy families

I took some unfiltered wax directly from the steam wax extractor (full of propolis and all sorts of other lumps), melted it down in my slo cooker and then crudely painted it on the inside of my poly bait hives.

If you value your marriage I suggest having a dedicated slo cooker for this 😉 .

Not exactly encaustic art, but it smells good

The paintbrush will not survive, at least not in a way that will allow you to use it for anything other than wax in the future. Use a cheap one.

I’ll report back later as to whether this experiment is a success or not, though I see no reason why it won’t work.

{{1}}: No guarantees!

{{2}}: OK, slight exaggeration, but certainly anywhere cooler/wetter/windier and more civilised than the Home Counties.

{{3}}: No.

{{4}}: Though we’ve had 35 mm of sleety rain today and the hills are now snow covered, so it’s clearly not in any rush. However, I did hear my first willow warbler yesterday.

{{5}}: I’m of course referring here to other beekeeper’s swarms; my own bees are far too well managed and polite to just up and leave. Ahem!

{{6}}: More than a little daunting, but Thomas was very gracious and contributed a lot to the subsequent Q&A.

{{7}}: Don’t do this at home!

{{8}}: A view supported by the inevitably more professional studies by Seeley.

{{9}}: You can thank me later.

{{10}}: I’ve tried a couple of times, unsuccessfully.

{{11}}: An oblique reference to the 2004 Renault Megan advert “I see you baby (Shakin’ that Ass)” featuring Fatboy Slim’s Remix by Groove Armada … you had to be there.

{{12}}: It might be easier to get your running shoes on and chase the swarm.

{{13}}: A rare occurrence in the UK.

Join the discussion ...