The year without summer

The title is hyperbole, of course. Meteorological summer only started three weeks ago, so it's still got about 10 weeks to prove itself.

But it hasn't started well 😢.

After a warmer-than-average winter, colonies came through the winter strongly, but things then stalled and have remained stalled for several weeks now.

At least half my trips to check on the bees over the last seven weeks have involved opening hives in the rain. Some just had me dodging intermittent light showers, muddling through when I failed to dodge them, but generally getting what needed to be done ... er, done.

One, in early May, involved the unfortunate coincidence of a near-Biblical deluge with my only opportunity to check the colonies. I got through it, but it was a dispiriting experience (for me and the bees).

However, last weekend was even worse.

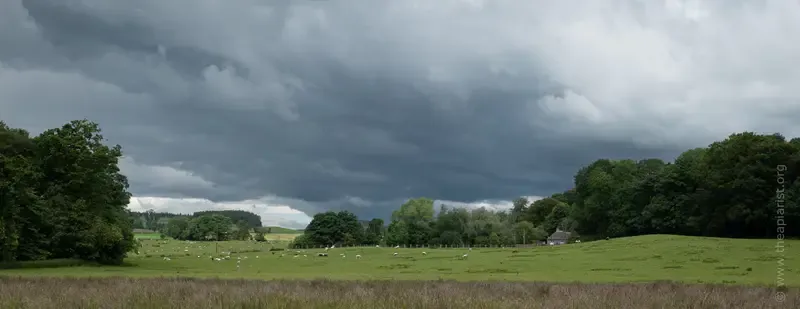

I drove across to the apiaries under threatening skies, it started raining well before I arrived, and continued largely unabated until I finally abandoned things in disgust the following afternoon.

I spent half my time sheltering under trees, in the car or in a lean-to shed with a ride-on lawnmower for company, and the remainder squelching around getting more frustrated as I got ever-wetter.

I finished the second day in a saturated beesuit, emptied the water out of my boots, changed out of my sodden clothes and drove home in a very bad mood.

I'd achieved about 20% of what I'd planned to do.

Why inspect in the rain?

Three groups of beekeepers inspect their colonies in the rain:

- the commercial beefamers; with lots of colonies, even with a 9, 10 or 14 day inspection cycle, they must be checked, come rain or shine. If a day is missed, then there will be double that number to check the next day.

- the deeply conscientious; if you understand the invariable nature of the development cycle of bees - particularly queens - then you will be aware that some hive manipulations are time-critical. You can postpone an inspection, but the emergence of queens is largely unaffected by wet or cold weather. They will emerge on time ... and possibly earlier if you inadvertently grafted larvae that were a little older than intended.

- the terminally disorganised.

I've always been a member of the third group, but strive to be a member of the second.

There's no chance I'll ever belong to the first 😉.

My own hive inspection schedule is built around a one-week cycle. This works well in terms of swarm control and for the majority of hive manipulations including things like queen rearing.

Due to the distant location of most of my hives - something I hope to soon resolve - it also fits with inexpensive cheap hotel reservations, pre-booked months in advance. Since the weather forecast cannot be relied on for tomorrow, I ignore it completely when booking 'every Sunday night from April to July'.

Beekeepers and fishermen

I've been both, so speak from experience. These two groups have several things in common:

- professionals work hard, often in physically-demanding conditions (at least, I expect they do ... I'm the very antithesis of 'professional' as these pages often demonstrate), for rewards that do not reflect the effort expended {{1}}

- amateurs have a tendency to exaggerate;

- 'you should have seen the one I lost',

- 'this big' {{2}},

- 'twelve supers per hive', and probably 'filled overnight',

- 'averaged over 75 kg per colony'

- there's always something wrong with the weather

- 'not biting, too bright'

- 'too wet' {{3}}

- 'no rain, the lime totally failed'

- 'early Autumn gales, they ate all the heather honey'

And this year, the problem has been both the cold and the rain.

I’m the proud owner of 800 empty honey supers 😕

— The Sheffield Honey Company 🍯🐝 (@SheffieldHoney) June 14, 2024

Big and small ... the woeful weather affects us all

Start as you mean to go on ... then don't

Across the UK the winter and spring temperatures were a degree (°C) or so warmer than the 30-year average. I discussed this in mid April under the strapline "Everything is a bit earlier and a lot wetter than last year."

I'm not generally a fan of warm winters. I like the certainty of a brood break and the opportunity it provides to really hammer the Varroa population with a judiciously timed application of oxalic acid.

However - although warm(ish) - we'd had a brood break, I'd slaughtered the majority of the remaining mites, and the colonies really took off once the spring pollen and nectar became available.

I found the first open queen cell in the third week of April, on the same weekend as the first supers were added (both earlier than any year since 2015). The oil seed rape (OSR {{4}}) was looking pretty good, and there was every reason to hope for a bonanza spring crop.

Strong colonies and flowering OSR, coupled with weather that's warm and dry enough for foraging, can generate those "I'm running out of supers" problems that beekeepers complain about (whilst secretly feeling smugly pleased ... it's a nice problem to have).

And then things went a bit pear-shaped.

Rather than inexorably rising through late April, May and early June, the temperature plateaued and then dropped. The last week in May was exceptionally wet, as was the second week in June. This reduced foraging significantly, slowing the rate at which the supers filled.

But it had other effects as well.

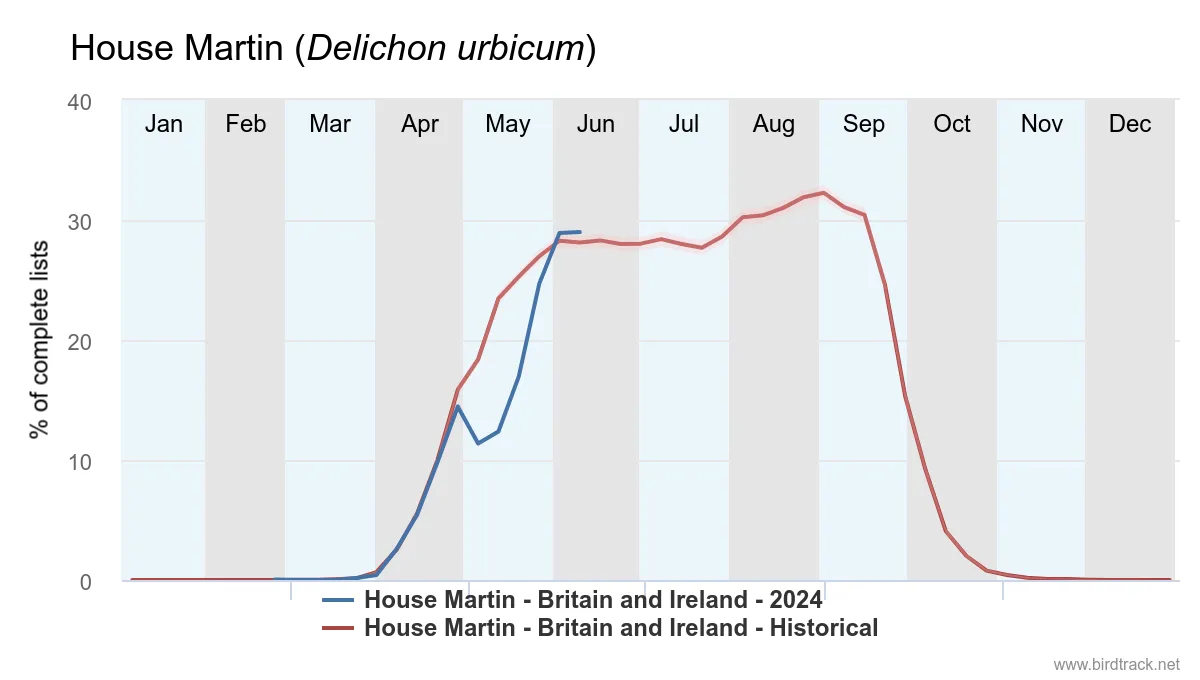

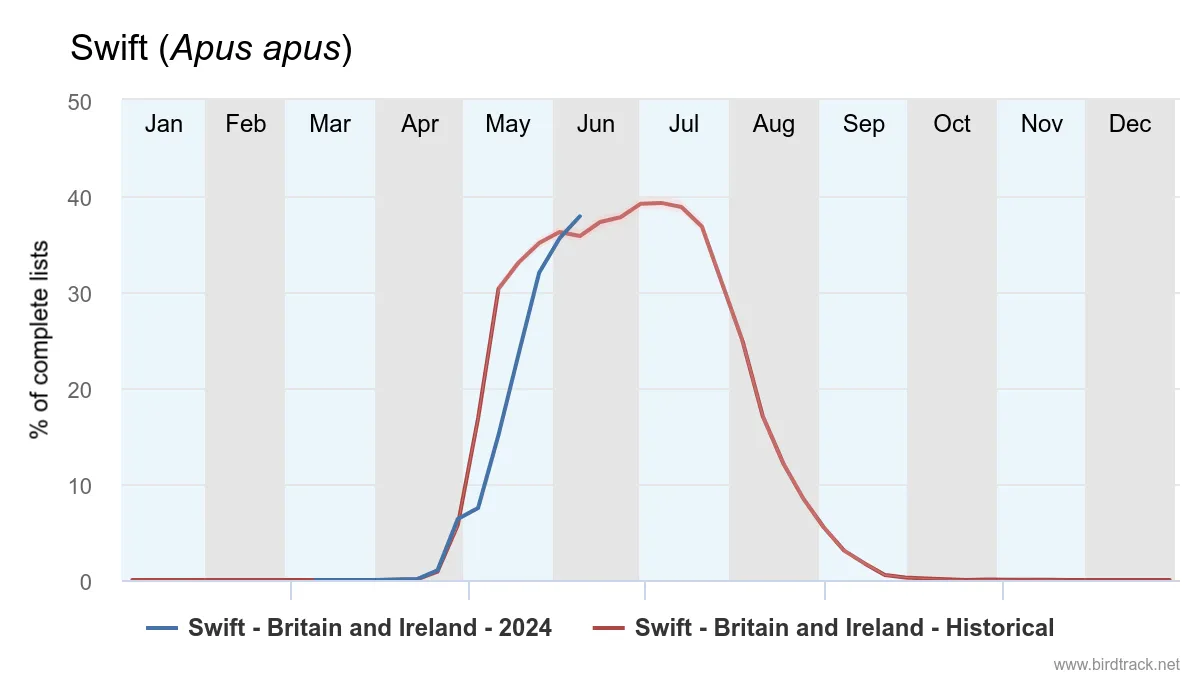

House martin (left) and swift records, UK 2024 and historical. Data from the British Trust for Ornithology.

One really obvious impact - evident from data collected country-wide - was the delay in the arrival dates of house martins and swifts. These insectivorous birds stall their northwards migration if there are insufficient flying insects. By the end of May, things had caught up, but the same could not be said of the beekeeping season.

The year without a summer

The original 'year without a summer' was 1816. The eruption of Mount Tambora (now in Indonesia {{5}}) the previous April launched so much ash into the atmosphere that the average annual global temperatures were reduced by 0.4-0.7°C.

That doesn't sound much, but the temperatures during the summer growing season in Northern and Western Europe were reduced by 2-3°C.

Crops failed, there was widespread famine and food riots.

There were knock-on societal effects. Artists painted the rich red hues of the fabulous sunsets (caused by the atmospheric particulates), the lack of oats to feed horses led to the invention of the velocipede, and Lord Byron, Mary and Percy Shelley and John Polidori escaped to the Villa Diodati in Switzerland to tell ghost stories.

Two of these, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley and - indirectly - Byron's short story The Vampyre (written by Polidori), are now considered classics of literature.

I'm not aware of any records of the beekeeping in 1816, but I expect it was a bit of a shocker.

2024 is not like 1816. Although temperatures - particularly for queen mating - have been depressed, there's still a reasonable chance that there will be a summer, and it might even be good for the bees.

However, the early summer has been quite challenging, and it has created a number of problems for beekeepers.

The other difference of course is that 1816 produced some literary masterpieces ... I'm certain that my miserably wet visits to the apiary will result in nothing of the sort.

Supers

Supering early helps reduce the pressure on space in the colony, and so contributes to swarm prevention. In a strong nectar flow, it also provides 'drying space' for nectar with a high water content.

If the nectar flow continues, the space in the comb is gradually filled and the ripened honey is capped off to preserve it. The ideal situation is that the supers are completely filled with capped honey as the nectar flow finally dries up.

But achieving that takes a combination of good forage (so there's nectar available), good weather (so that foraging is possible) and good judgement by the beekeeper (in not adding too many supers for the forage and conditions available).

We've not really had any of these this year 😔.

This year, the flying start in late April meant that I overestimated the supers needed ... by as much as 100% in a couple of cases. I had colonies with four supers when two would have probably been sufficient.

Actually, the opening sentence of the last paragraph is not quite accurate; I estimated the number of supers (based upon colony strength, and the potential forage and likely spring/early summer weather) correctly, but the weather didn't 'play ball' and foraging was restricted, meaning I'd provided too much space.

Consequently, when clearing the supers, some were packed, but others contained many wholly, or partially, empty frames.

I've yet to extract (the supers are stacked in the warm to delay granulation) but expect the overall crop to be a little below average. Not a disaster, but much less than I'd hoped for.

Clearing supers with ripe honey

There are a few things I consider when removing the honey supers:

- is the honey 'ripe', with a low enough water content (less than 20%) that it will not ferment in storage? {{6}}. I've dealt with this topic - and the informative 'shake test' - relatively recently, so won't repeat myself here.

- is there sufficient honey in the super to make it worth extracting? It's easy to balance full frames, but less so if they're partially empty.

- if I take all the honey, might the colonies starve if there's a pronounced 'June gap'?

- if I empty the supers will the brood box be left so packed with bees, that swarming might be induced?

All of these - except for the first item in the list - involve a combination of experience, good judgement and 'guesstimates'.

Quite a bit of the latter if I'm honest.

Although I rarely look in the supers during inspections {{7}} I do try and judge their weight. As the honey is ripened, I try and move the heaviest supers to the top of the stack.

If a super contains a couple of filled and capped frames, with the rest largely empty, I'll shuffle frames in the stack of supers to move the full ones towards the top.

This is all very inexact and a little bit arbitrary ... but it does make the next bit easier.

I add the clearer above the super I consider is:

- not worth extracting, or

- full or partially full of unripe honey, or

- needed by the bees if it rains for a fortnight

Unless, by exceptionally good judgement a miracle, I've got a stack of completely filled supers, this usually means I leave one (or this year two, in some cases) supers on each hive.

Removing supers in heavy rain

I've done a lot of this in the last fortnight.

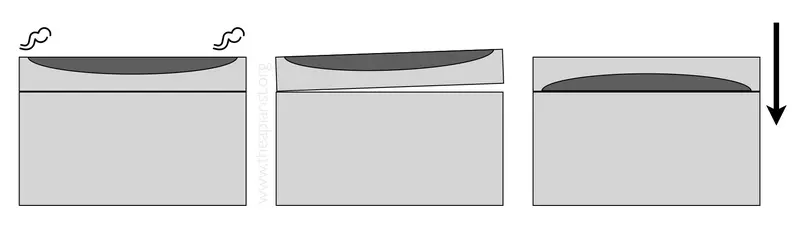

There are two problems here ... the first is that all the bees are 'at home' as it's too wet to forage. The second is that a heck of a lot of bees are cleared out of the supers, and most of them congregate within the space created by the deep lower rim of the clearer design I use.

These clearers work exceptionally well.

I put some on at 10 am one day last week and estimated that well over 80% of the bees had moved down when I checked again at 4 pm on the same day. Used overnight there are rarely more than a dozen or two stragglers, even if the super contains unripe nectar {{8}}.

On a dry day I just remove the supers, gently lift the clearer and give it a sharp shake or two over the top of the open hive. Inevitably, some bees miss the target and end up on the ground, or the hive stand.

That's not a problem on a warm, sunny afternoon, but potentially fatal in a downpour {{9}}.

To avoid this I've found that gently - and quickly - lifting one side of the clearer by a half centimetre or so, then sharply banging it down onto the hive (perhaps then repeating it on the opposite side of the clearer) clears most of the bees, without covering the ground, the stand, my boots and the adjacent hives with clumps of disoriented bees.

Do this quickly enough and you don't crush bees between the hive rim and the clearer either.

I usually give them a puff or two of smoke through the clearer 'exits' first as well.

If you want to inspect the colony, do so before adding the clearer. Once the supers are empty, the brood box will be stuffed with bees, and it will be much more difficult to see things. This also means that the inevitable disruption caused by bashing the clearer down will not agitate the bees before you inspect them.

Queens

Suffice to say, the combination of depressed temperatures and double the average rainfall over the last 7 weeks has had quite an impact on swarming and queen mating.

By 'quite an impact' I mean there's been almost none of either.

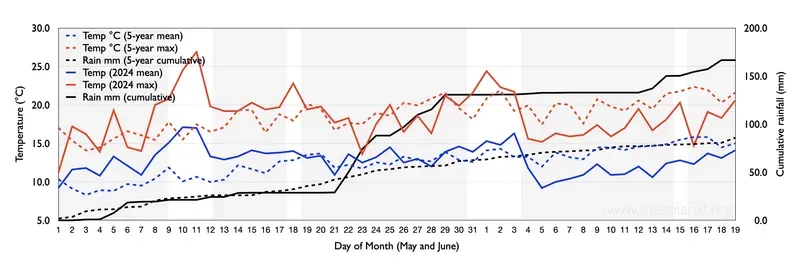

In the graph above, the 2024 data are plotted in solid lines, with the average of the past 5 years in dashed lines. I've plotted the mean temperature (°C) in blue, the maximum daily temperature (°C; both on the left-hand axis) in red and the cumulative rainfall (mm; on the right-hand axis) in black.

Large parts of May and June have been reasonably dry this year, but when it's been wet, it's been very wet. And when it hasn't been wet, it's been cool.

My 'back of an envelope' calculations - taking account of the mean and the maximum daily temperature, the daily rainfall (and when the latter two occur) suggest that - on average - a typical year might have ~24-28 days during the period graphed in which queen mating could occur.

This year, that number is probably no more than 10 days, and possibly as few as 5 or 6 (the unshaded areas in the graph above).

I'll discuss these calculations at some point in the future, as I don't currently know whether some (or any 😢) of my queens are successfully mated.

So, from a beekeeping point of view, what did I see in the hives?

(Almost) no swarming

I've lost no swarms per se, but I did lose one or two clipped queens in late April or very early in May when colonies attempted to swarm.

Typically since then, when conducting an inspection, I'd find a laying clipped queen and one or several sealed queen cells. It wasn't unusual to find an emerged virgin queen and a laying clipped queen in the same box.

Many of the sealed queen cells contained mature virgin queens. If I gently uncapped the cell, the virgin queen (VQ) would come scuttling out.

I've lost count of the number of hives I could hear a piping queen in. This is the characteristic sound made by a virgin queen.

With dire weather forecasts for the fortnight or more after the inspection, I would usually release the VQ and let the colony sort things out. In better weather, I'd have performed some sort of swarm control {{10}}. However, there seemed little point in splitting a production colony with almost no chance the VQ would get mated within the foreseeable future.

Whether this was the right strategy will need the benefit of hindsight ... in many boxes the VQ apparently disappeared, in others both queens remained present.

Queen mating

My 'back of the envelope' calculations are crudely based upon temperature and rainfall stats from an enthusiasts local weather station.

We know a lot about queen mating flights; 80% take place between 1 pm and 4 pm, they average ~18 minutes duration and the queen takes ~5 over a period of 1-5 days ... do the maths!

The proof of the pudding is that I'm only aware of one queen getting successfully mated in the last 6 weeks or so.

It has been dire.

Time after time, I'd open the box to find 'polished cells' in the centre of what should be the brood nest, and either no sign of a queen, or a virgin scampering around getting hassled by the workers.

This 'one in six weeks' number may be wrong; I abandoned most hive inspections last weekend due to the deplorable weather. Perhaps they all got mated in mid-June, when the temperature briefly (for just 90 minutes on the 15th!) exceeded 20°C.

A similarly brief period of warm weather occurred on the 19th.

Queen rearing

Ha! Don't make me laugh.

I've raised a lot of queens, but it's been a futile exercise.

However, not all is lost. I've learned a lot about caging queen cells early, temperatures they can withstand (12-15°C for hours), and the effect of humidity on VQ's allowed to emerge in the incubator.

I just have no idea whether the queens have subsequently been successfully mated ... but hope to soon find out.

And, if they're not, there's still time to rear a couple more batches ... and pray for better weather.

Top(ical) tip

Sponsors of The Apiarist get a 'Top Tip' in their Bees in the News monthly newsletter. However, the next of these is a fortnight or so away, and this tip is both time-sensitive and one I've given a few years ago.

UK readers may be aware that there's an election on the 4th of July.

There are 650 seats and a record total of 4,515 candidates. Of these, 3,685 will be disappointed and - if the polls are right {{11}} - hundreds will be from the largest 3-4 parties, all of which produce lots of advertising.

And some of this advertising is on weatherproof printed Correx signs. Correx has numerous uses in beekeeping - from landing boards to roofs.

It's magic stuff.

Many unsuccessful candidates are unlikely to stand again, so the printed Correx advertising will be discarded or recycled. Look out for piles of blue or yellow or (less likely) red Correx sheets near your local constituency office (or ditches in constituencies with particularly poor losers).

Of course, not all of this Correx will be useful. The O'Hara sign above won't make anything much bigger than a Varroa tray. However, if the unsuccessful candidate is called Christopher Cholmondeley-Pennell you might be able to build a top-bar hive - or, with a couple of boards, a bee shed - from Correx.

Christopher Cholmondeley-Pennel has 31 characters in his name. The informative democracyclub.org.uk lists 18 candidates with names containing 31 or more characters, and a further 99 with at least 25 characters.

Now, if that isn't a top tip, I don't know what is 😉.

Sponsorship

If you found this or other posts useful, informative or entertaining, then please consider becoming a sponsor of The Apiarist. It costs less than £1/week and ensures you receive every newsletter, including those - like Bees in the News #2 on the 5th, or the post last week on grafting for queen rearing - available to sponsors only.

Alternatively, you can help offset the damp rot by fuelling my caffeine dependency and spread the word to encourage others to subscribe.

Thank you

Notes

This post was published on the 21st of June, the summer solstice, and also the start of astronomical summer. Perhaps everything will improve from now on? If so, the post is mistitled and should have instead been called 'Arrested development' (which was the original intention).

The bell heather is flowering in the hills and the blackberry is just starting. Enjoy the long evenings before they start to shorten.

{{1}}: It's the owners and equipment suppliers that drive the Ferrari's.

{{2}}: Holding one hand out to indicate the length of the catch.

{{3}}: For fish?!

{{4}}: Canola for my American readers.

{{5}}: That reads weirdly ... the volcano hasn't moved, but the country used to be called the Dutch East Indies.

{{6}}: Or worse, when sitting on the shop shelf with a hefty price tag.

{{7}}: Unless I suspect the queen has somehow got above the queen excluder. Grrrr.

{{8}}: If there are hundreds of bees left it's likely that the colony is queenless ... or that the queen is in the super!

{{9}}: Remember, I'm both conscientious and disorganised.

{{10}}: I've been carrying a Taranov board around in the car for over a month in the hope of trying a new method of swarm control ... another futile exercise.

{{11}}: And they're unlikely to be completely right.

Join the discussion ...