2021 in retrospect

Déjà vu?

Well … not really.

This time last year I wrote my 2020 in retrospect post. Looking back the last few years I’ve always tried to post these retrospective reviews of the season a week or so before Christmas.

In December 2020 we had a rapidly rising number of Covid cases being diagnosed, peaking in early January at ~68,000 a day. One year later – actually a little less than one year – we’ve just surpassed those worryingly high numbers.

So, not déjà vu at all … as that means the feeling of having already experienced the present situation.

We have experienced it already 🙁

Like chalk and cheese

Covid and the lockdowns of 2020 had a dramatic impact on my beekeeping. I did the bare minimum to maintain the colonies. This involved little more than some rigorous swarm control followed by feeding them up for winter.

2021 has been completely different.

Despite the self-imposed restriction of living 150 miles from the majority of my bees, I had a really busy time and was beekeeping more or less all season.

And it was a very good season.

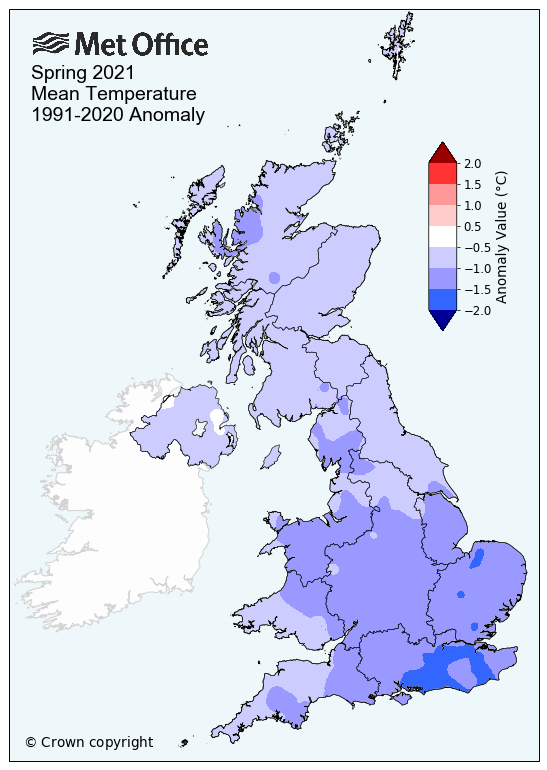

After a cold, late start to the year {{1}} I was concerned that the colonies weren’t going to be strong enough to exploit the oil seed rape and other early nectar.

I needn’t have worried.

By mid May the colonies were booming and I managed the biggest spring honey harvest since returning to Scotland in 2015 {{2}}.

The honey bonanza was repeated again in the summer, again with a record crop.

What was particularly rewarding was that these good harvests were achieved from significantly fewer production colonies than previous years.

This isn’t really a case of Less is more, it just reflects what a good year it was here.

Downsizing

I had lived in Fife since 2015. From 2018 I’d spent increasing amounts of time on the west coast which – with lockdown – had included the majority of 2020.

For many reasons this was preferable and, with no expectation of Covid (and all it had entailed) disappearing anytime soon, we took advantage of a brief hiatus in government restrictions {{3}} to sell-up in Fife and move permanently to Ardnamurchan.

The move was in February 2020 … and there are still some things that have yet to be unpacked.

The one thing I didn’t move was any bees.

Bees in Fife, like ~98% of the UK mainland, have Varroa. In contrast, the Ardnamurchan peninsula, together with some parts of neighbouring Morvern and Knoydart, are Varroa-free.

Therefore, in preparation for moving away from Fife altogether, I have been reducing my colony numbers on the east coast this year.

As many beekeepers know, the best way to do this is to split colonies into nucs and pop in a ripe queen cell.

Bingo!

Three weeks later you should have a mated queen and two to three weeks after that you will have a nuc ready for sale.

Have you seen the price of nucs recently?

All of which meant that I spent much of the first half of the season rearing queens.

Queen rearing in Fife

I probably enjoy queen rearing more than any other aspect of beekeeping.

I think I’ve previously recounted first reading Hooper’s Bees and Honey book and skipping over the queen rearing chapter thinking ‘Why on earth would I want to do all that?’.

Have you seen the price of nucs recently?

As Hooper said, there are few things more satisfying than working with a calm and productive colony headed by a queen you have reared.

And he was right.

I started queen rearing on the 10th of May. In retrospect, despite getting good acceptance (10/10) of the larvae, this was a bit early as subsequent queen mating was patchy and slow.

If at first you don’t succeed …

The second and third batches of queens (on the 1st and 7th of June) were much more successful and the better weather in June improved mating success. Overall, almost 75% of grafted larvae resulted in mated queens.

In my experience, this is about as good as it gets. At least with my rather amateur fumbling.

I usually work with the expectation of getting about a 50% mated queens from larvae grafted, and am more than happy if I achieve much more than this.

All of my cell raising in Fife used my favoured ‘Ben Harden‘ system which I described way back in 2014. I often supplement these with pollen but this year – as I had no stored pollen available – I used pollen substitute patties. There probably wasn’t a shortage of natural pollen but the bees still wolfed these down and I doubt they did any harm, even if they didn’t do much good.

The resulting queen cells were added to 2-3 frame nucs for mating and then grown on.

In the good weather the nucs rapidly outgrew the boxes and I found myself stripping out frames of brood to hold them back when needed. The brood frames removed were used to boost production colonies, no doubt helping them collect a bumper summer crop.

West coast queen rearing

The season on the west coast starts later and develops more slowly than on the east. I suspect this is due to the absence of any oil seed rape, and possibly limited amounts of other early season sources of pollen and nectar.

Nevertheless, by late June I attempted my first round of queen rearing. With a patchy nectar flow – and despite feeding syrup – getting larvae accepted was tough. I also struggled to get the queens I did produce mated … although it wasn’t an unmitigated failure, it was in stark contrast to my experience on the east coast.

I’m pretty sure the poor queen mating success was down to a shortage of drones. This is a very sparsely populated area … of both people and bees. Next year I plan to boost drone production in all my good colonies, even if it’s at the cost of reduced honey production, to help populate the local drone congregation areas.

I used a Morris board for cell raising on the west coast. This works much like a Cloake board which I have used very successfully in previous years. I need a better season to determine whether it offers benefits over the Ben Harden setup.

Beekeeping is an exquisitely ‘local’ activity. Despite being at a broadly similar latitude and only ~150 miles apart, the bees in my east and west coast apiaries develop at different rates and swarm at different times. It’s probably going to take me a year or two to ‘get in the groove’ {{4}} with queen rearing on the west coast.

Record keeping

To help me remember what didn’t work last season – or to aid my recall of the few successes I did enjoy – I keep records.

In previous years I’ve done this with bits of paper that I carry around with me from apiary to apiary in my bee bag.

However, the combination of the house sale and my shockingly bad organisation {{5}} had resulted in me starting the 2020 season with no blank printed forms on which to keep records.

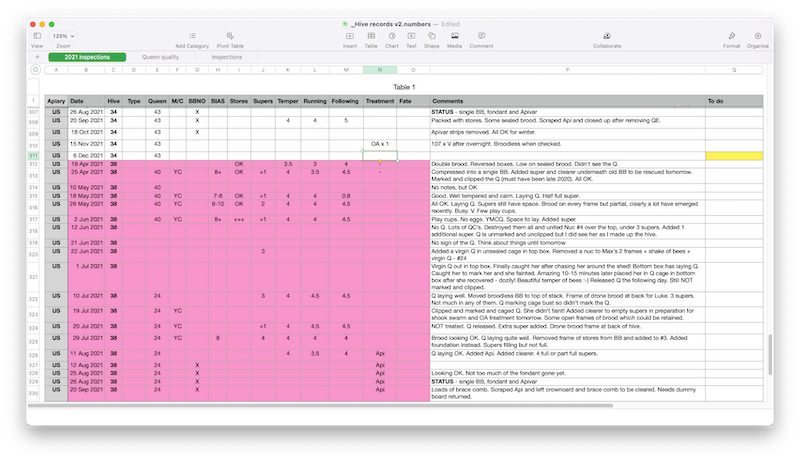

I therefore cobbled together a slightly expanded version of the form on a spreadsheet and used this for all my record keeping.

I always have a laptop with me when travelling and the majority of my bees on the east coast are in apiaries with at least some shelter. Therefore, rather than taking notes and transcribing them to the spreadsheet I just typed them up, there and then, during the inspections.

The downs and ups of being a digital nomad

The N, M and comma keys are now sufficiently gummed up with propolis that the laptop is almost unusable.

D’oh!

However, keeping records like this has been a revelation. Not only are my records more complete than usual, they are also a lot more useful.

For example, they are directly searchable. If I search for ‘OA’ I can find the 18 instances when I referred to this during the year – all of which are in the Treatment column.

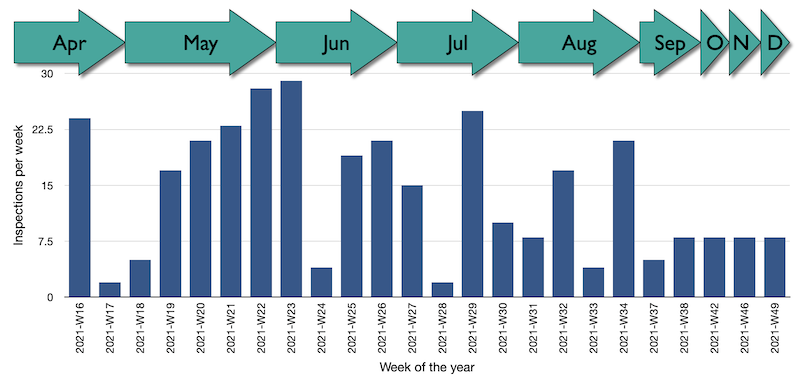

With a little Pivot Table magic I can see how busy I was during the season.

I’ve not broken this down into east and west coast apiaries, and I’ve exclude instances when the brood box wasn’t opened or when I did nothing but add syrup/pollen patties etc.

Over the season I inspected something like 340 colonies, but as is clear from the graph above, the bulk of the work was in May and June. Several colonies haven’t been fully inspected since late July, though all those on the east coast have had the Apivar strips added and removed.

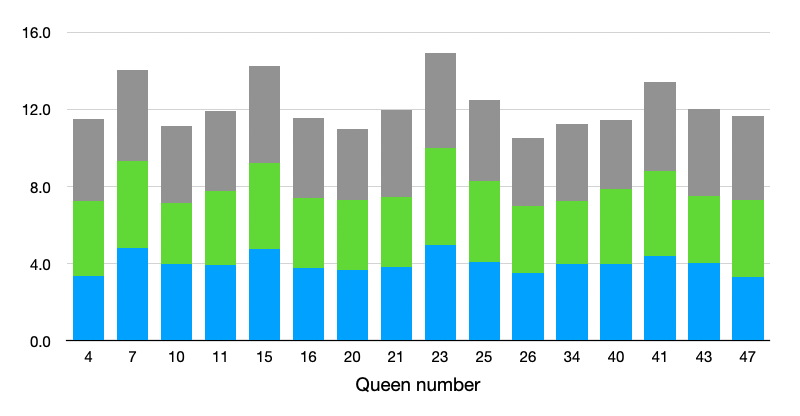

Big deal … show me something useful

OK, I agree the graph above is of little use. Perhaps more beneficial is the ability to easily get an idea of various aspects of colony performance.

For example, when I’m queen rearing I only want to select larvae from my best colonies.

That’s not necessarily the colony I thought was best last week.

Perhaps I was particularly clumsy that week with an even better colony?

Maybe I have simply forgotten how psychotic the apparently good colony was in previous weeks?

It really should be the colony that has, over the range of characteristics I score, performed best over the season.

My queens are numbered, or at least the boxes they are in carry a unique queen number.

Therefore, by being careful not to duplicate queen numbers during the season, it’s possible to get an idea of which colonies (queens) have performed best … again with a little Pivot Table magic.

These are cumulative averaged scores of three separate criteria e.g. temper or steadiness. I don’t keep records of honey weights, or longevity, or swarminess, or any number of other criteria … but I could if I wanted {{6}}.

Next season I’ll have a pretty good idea which queens to select larvae from when I start queen rearing.

Mid-season scare

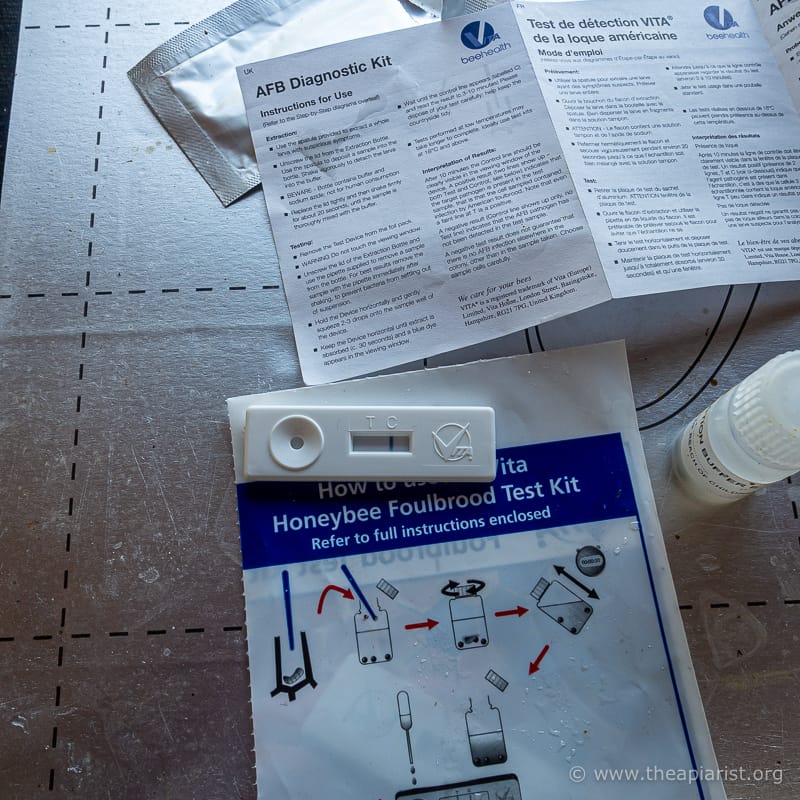

At some point late in July I received the dreaded ‘AFB within 5 km’ email from the National Bee Unit.

Irrespective of how careful you are in previous inspections, or of how rigorous you are with apiary hygiene {{7}}, these emails are always worrying.

At least they are to me 🙁

I sold my first-borne child and purchased a load of AFB test kits, ordering them en route to Fife and collecting them from Brian in Thorne’s of Newburgh before arriving at the apiaries.

I then spent an entire day going through every frame {{8}} in every hive in the ‘at risk’ apiary and another site that I use.

It was a busy day.

After looking at a few hundred thousand cells you start to get paranoid.

Inevitably you’ll find a few partially capped cells … after all, they can’t go from open to capped without – at some point – being partially capped. I didn’t lateral flow test every one, but I did the ropey larva test on a large number … everything was negative.

Phew!

I was subsequently told that, although additional apiaries (one or more, bee inspectors are, rightly, careful not to disclose confidential information) were found with AFB, all were directly linked to the index site i.e. AFB transmission involved the beekeeper-mediated transfer of bees or contaminated equipment, rather than through drifting or robbing by the bees alone.

Forewarned is forearmed … next season I’ll be careful to check the colonies as they build up in the spring.

The dying of the light

I’m writing this as we approach the shortest day of the year which, here on the west coast, is about six and three quarter hours long.

There’s not much light, but what there is can be stunning …

It’s a good time to look back over the season.

To work out what worked and what didn’t.

Overall 2021 was pretty good as far as my bees were concerned. The season contained a normal range of surprising successes and abject failures, caused – in equal measure – by my usual insightful interventions and appallingly cackhanded meddling.

It was fun.

I learnt a few new things.

I probably re-learnt a lot more 😉

And, like every season, I saw things I’d either never seen before or not been alert enough to notice.

Herding drones

I’ll end this retrospective with a photo taken on the last day of August as I transferred a colony to a new brood box.

It’s not a particularly good photo as I had to carefully put down the frame I was holding and scrabble around for my camera.

In the far back corner of the hive, diametrically opposite the entrance (which was reduced to help the colony repel wasps), there was a ‘clump’ of drones. They were tightly wedged into the corner of the hive and – at least to me – it looked as though they were being herded there by the workers.

We all know that drones are evicted from the colony as autumn approaches.

Their job is done.

Actually, to be pedantic, if they are still alive in early autumn they have singularly failed to do their job 😉

Whatever … they are surplus to requirements as far as the colony is concerned.

Usually you see the drones being turfed out of the entrance of the hive.

I think this photo shows what happens to the drone inside the hive. The workers pester and harry them. Either they try and hide in the corners of the hive, or they are effectively herded there by the workers.

It can’t be a lot of fun being a drone in late August 🙁

{{1}}: Everywhere … and even more marked in the south east of England.

{{2}}: Not as much as I’d got in the best years in Warwickshire, but not far short.

{{3}}: And the booming post-lockdown housing market.

{{4}}: Do people say this anymore? Does this show my age?

{{5}}: Largely the latter, but we also discarded my dodgy old printer when emptying the house.

{{6}}: And if I didn’t have a lot of much more interesting things I’d prefer doing.

{{7}}: And, let’s face it, I know I could always do better.

{{8}}: At least every frame with brood on it, which – for many hives in late July – means every frame.

Join the discussion ...