2020 in retrospect

Almost exactly a year ago I wrote my retrospective review of the 2019 season.

At the time I was thinking “What a nightmare! If I never again have a year like that it’ll be too soon.”.

This was due to a major fire in my research institute which terminated a 30 year research programme and drowned me in a tsunami of administration.

The little beekeeping I did in 2019 kept me sane. Insurance issues and a new research facility took every waking hour. There was no ‘active’ queen rearing and my swarm control involved littering half of Fife with bait hives.

I piled on the supers, crossed my fingers and hoped for the best.

And got away with it 🙂

But by February 2020, the anniversary of the fire, it was looking as though those problems were just the hors d’oeuvres.

‘Coronavirus’ was a word transitioning from white-coated virology nerds with expansive foreheads to everyday, and then every minute, usage.

Covid and stockpiling

The word ‘Covid’ was first used in 1686. For its first 333 years it referred to an Anglo-Indian unit of linear measurement {{1}}. On the 11th of February it appeared as a hashtag on Twitter and today it features a dozen times on the BBC homepage.

By early March it was clear that major societal changes were going to be needed to control virus transmission. A couple of days after spring talks to Oban beekeepers, Edinburgh and District BKA and the SNHBS the country went into lockdown …

… by which time I was jealously guarding my panic-bought toilet rolls {{2}} on the remote west coast of Scotland.

The national beekeeping associations negotiated travel arrangements for animal husbandry purposes and the rest, as they say, is history.

I’ve already written about the practicalities of the small amount of long distance beekeeping I did in 2020. I won’t rehash the gory details here, but will make a few more general comments.

Highs and lows

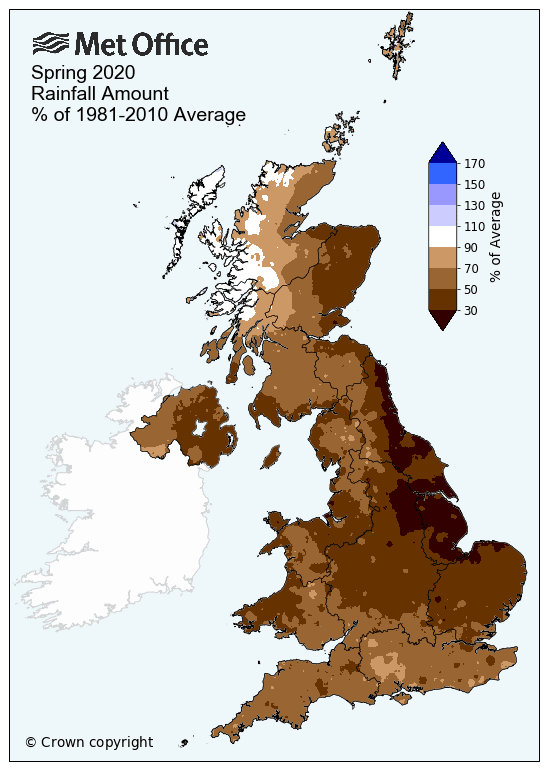

It was a pretty good beekeeping start to the year. The spring was significantly drier than the 30 year average. This meant that the bees could get out and exploit the oil seed rape (OSR).

Consequently the honey yield per colony was the best I’ve had in the five years I’ve been back in Scotland. I think it would have been even better had I been present to add the supers in a more regulated manner … and to remove them before they crystallised.

In contrast, the summer was characterised by a series of lows … low pressure systems, bringing more rain than usual.

This probably reduced the time available for foraging, but perhaps was compensated by better nectar flows. My two main production apiaries performed very differently.

One generated almost no honey per hive, the other again generated record yields of outstandingly flavoured summer honey.

Guess which apiary contained more production hives?

Typical 🙁

Putting the control into swarm control

Swarm control usually involves careful observation of colony development coupled with a timely intervention to split the colony and prevent swarming.

The timely intervention is often at different times for different colonies, even in the same apiary.

There was none of that this year.

With only about four inspections all season I implemented swarm control in the majority of colonies well before queen cells developed.

The method should be termed something like split and hope 😉

In practical terms it involved preemptive application of the nucleus method of swarm control.

The only decision I made for each colony was whether to apply swarm control or not.

I then made up the queenright nucs all on the same day. The nucs were made significantly weaker than usual to delay the time when I’d have to expand them up to a full colony.

Overall the approach worked very well, at least in terms of swarm control, as none of my colonies swarmed 🙂

The colonies that weren’t split were given lots of room and a combination of inspired judgement a long June gap and some iffy midsummer weather meant they stayed together.

Hieroglyphics

I need to go back through my notes to determine how individual colonies performed in terms of honey production. Other than the absence of any summer honey from one apiary, were there differences in terms of the amount nectar collected between colonies that were split or not?

Unfortunately, the (frankly) manic beekeeping that resulted from compressing everything into a few inspections over the season meant my notes are, in places, rather sparse {{3}}.

Too weak to split

+3 supers Q+ good

WMCLQ WTF?

Grrr {{4}}

Deciphering my hieroglyphics will necessitate a large glass of shiraz and a long winter night – two other things, along with the loo roll, I have an abundance of at the moment.

Varroa management

The other reason I need to review my notes is to look at the relationship (if any) between the in-season colony management {{5}} and end-of-season mite levels.

I do have some reasonably good counts of the mite drop during late summer and midwinter treatments {{6}}. These are particularly reliable for the colonies in the bee shed because the floors I use have a tightly fitting Varroa tray, meaning that anything that drops, stays dropped {{7}}.

Cedar floor and plywood tray …

In addition, I’m confident that the colonies received their ‘midwinter’ treatment – in mid/late November – when totally broodless.

There were significant differences between the mite drops of colonies in the bee shed. Some dropped 250-500 {{8}} while others dropped less than 75. Those figures are totals over 8-9 weeks with Apivar plus the fortnight or so after oxalic acid treatment.

All other things being equal I’ll use the colonies with lower mite levels for queen rearing next season. For whatever reason, those colonies appear better able to manage their Varroa levels. Perhaps this is due to increased grooming or better defence (e.g. turning away potentially mite-laden drifting workers {{9}}). If their temperament is good and they overwinter well they will be a good choice to rear queens from.

Inevitably all things will not be equal, but at least I’ll have tried.

And I’m hoping to be doing a reasonable amount of queen rearing in 2021 … though after a devastating fire and a global pandemic I wouldn’t be surprised if the Earth was obliterated by an asteroid just as I start grafting 🙁

Going Varroa free

I’ve spent almost all year on the west coast, and will be spending increasing amounts of time here in the coming years. The area is remote, very sparsely populated and Varroa free.

It also has spectacular sunrises …

… and scenery …

Actually, until I imported {{10}} a couple of colonies, it appeared to be completely honey bee free. I’ve sourced Varroa-free colonies from an island off the west coast of Scotland.

I’ve often written about the importance of being ‘in tune’ with the local beekeeping environment. It’s already clear that the east and west coasts of Scotland {{11}}, despite being separated by only ~120 miles, have distinct climates, nectar and pollen availability.

What? No oil seed rape?

On the west coast there’s no OSR. In fact, there’s almost no arable farming at all. I’ll be interested to see what the bees access for spring and mid-season nectars. With mixed woodland, and more being planted, and lots of native flowers they should have a good selection.

There are some huge lime trees just down the road. These need rain to generate good levels of nectar, and rain is something else we have in abundance 😉

The main source of nectar is the heather. This is something {{12}} I have almost no experience of. In the Midlands I was always too busy to transport hives to Derbyshire for the heather. Fife, despite being in Scotland, has very little heather moorland and most beekeepers have to take their hives to the Angus Glens. I never bothered.

Now there’s acres of the stuff just up the hill at the back of the house. Not particularly good quality heather moorland, but lots of it.

I’ll return to this when I discuss planning for the season ahead, sometime in the New Year.

The Apiarist – online and offline

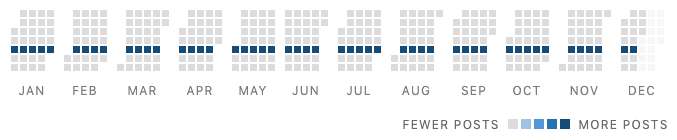

This is the 51st post of the year.

Regular as clockwork

With a bit of luck I’ll also scribble something for the 25th, so completing a ‘full house’ for 2020. It’s too soon to look at any year-end statistics, but it’s clear that lots of people had lots more time for lots more reading this year.

I wonder why?

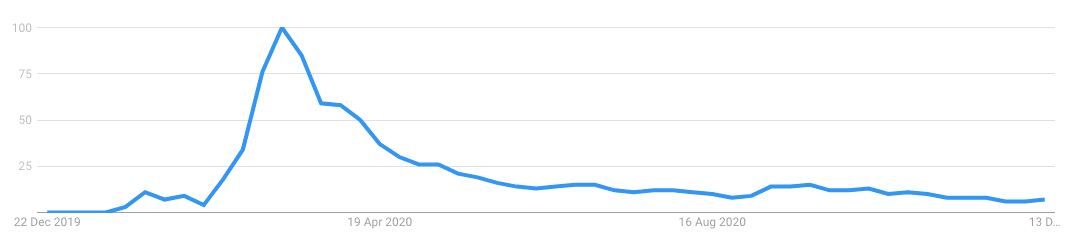

Everything came to a grinding halt in mid-June when a post featured on one of the Google news sites. In one afternoon the server was inundated with people eager to read about the June gap.

Thousands and thousands of them 🙁

Since most of them didn’t look elsewhere on the site I suspect the topic was a bit too niche for the majority of the internet illiterati.

After a couple of hiccups and a faltering stagger the server collapsed under the onslaught. I spent an afternoon moving it to a host with four times the capacity (at four times the cost) and it’s hung on gamely ever since.

Not only have beekeepers been doing lots more reading, they’ve also doing lots more listening and watching.

Online beekeeping talks

Many beekeeping associations – both local and national – have developed online winter talk programmes.

I’ve attended lively SBA Q&A sessions, BIBBA webinars by Adam Tofilski on preserving native bees, and I spent yesterday evening learning all about distinguishing Apis mellifera mellifera from ligustica or carnica or Buckfast or mongrels, care of the SNHBS.

And I’ve delivered more talks to bigger audiences this winter than in all of the last few years combined.

These talks – not mine specifically, but all of those available – fill the void between September and April. Although perhaps not the easiest way to establish new friendships {{13}} they are an excellent way to keep in contact with people from all over the country. In that regards they’re much better than ‘in person’ evening talks, and much more akin to the annual beekeeping conventions.

Though, unlike the conventions, my wallet doesn’t return emaciated from an hour or two going round the trade stalls.

Online talks are also good for keeping in contact with people on the other side of the county, let alone the country. It’s not unusual for my talk to be sandwiched by friendly banter between beekeepers separated by both distance and Covid.

Will this continue? I expect so. I don’t expect in person talks will start until 2022 at the earliest. However, I think – just as remote working will increase – online talks will be a regular feature of the winter beekeeping calendar. The benefits outweigh the slightly impersonal format, and many people appreciate the convenience of not having to travel {{14}}.

Science aside

The enforced downtime, with labs closed and staff furloughed, has enabled me to finally write up a backlog of papers on honey bee virus research. A few of these have featured on this site already, in discussions of whether DWV replicates in Varroa, or in bumble bees, and in the inexorable rise of chronic bee paralysis virus as an emerging pathogen of honey bees.

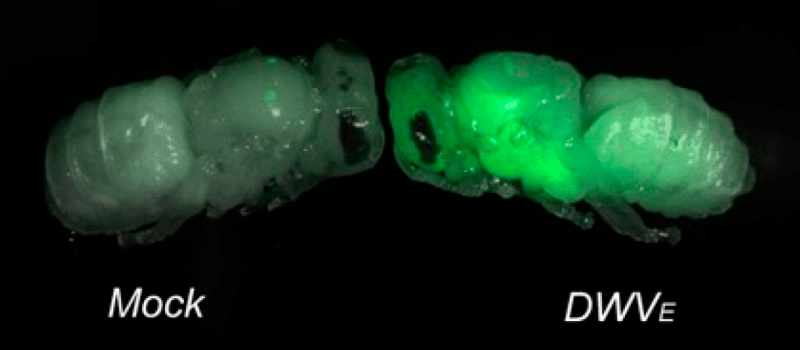

I’ve yet to find time to write about our green bees because I want to include a really elegant experiment we have yet to complete. These bees are infected with a virus that expresses a green fluorescent protein from a jellyfish. When visualised under UV illumination the individual cells and tissues in which the virus replicates are easily detected. More about this next year.

Several more papers are in the pipeline or in preparation, on rescuing hives with catastrophically high mite loads, on competition between different variants of DWV and on the landscape-scale control of Varroa.

Lessons learned

Considering the paucity of beekeeping this year I’ve still managed to learn a few new tricks and improve a few old ones.

I’ve learned how little intervention is required to manage colonies adequately (defined by good health and no swarms, though undoubtedly at the cost of maximising the honey yield).

‘Adequately’ because I also learned how unrewarding it was keeping bees without beekeeping.

For the first time I used air freshener to unite lots of colonies during a particularly busy long weekend when I requeened the majority of my hives. It’s a new trick to me, though widely used by others. Having used it, I’m now confident it works. I’ll use it again if I’m similarly rushed for time, but expect to usually rely on uniting over newspaper.

I’ve gained more confidence in accurately guesstimating how weak I can make up nucs, without them succumbing to robbing, wasps or starvation. Undoubtedly I was aided with reasonable weather and good nectar and pollen availability, but it will be a skill I’ll be able to use again in future years.

I also learned – or at least reinforced my appreciation of (as I’ve done this previously) – how to hold back the nucs, so preventing them swarm, by removing lots of brood {{15}}. The brood was used to boost honey production colonies which were requeening themselves. With some good judgement, and a big slice of luck, this all went very well.

The importance of regularly checking bait hives was also emphasised when I found this …

This season was unusual as I didn’t attract a single swarm to a bait hive, probably the first time that’s happened for a decade. Partly this was because I set so few out, but presumably it also reflected my dalliance with waspkeeping.

Finally, I’ve learned there are quicker ways to prepare spreadable ‘soft set’ honey that the interminable Dyce method. I’ve recently acquired a new honey creamer and the first fifty jars have been distributed to friends and family for Christmas. I expect very positive feedback {{16}} due to the extensive product testing and quality control applied during its preparation 😉

{{1}}: Of 14-36 inches in length (how could that be useful?) … no wonder it’s now obsolete.

{{2}}: Since this site has no sponsorship I hope you’ll take my promotion of Who Gives a Crap (Toilet paper that builds toilets) as a strong recommendation.

{{3}}: By which I mean unintelligible.

{{4}}: Actually, this was a different four letter word, resulting from my discovery of a queen that had filled three supers of drawn drone comb with brood.

{{5}}: Or possibly mismanagement … ?

{{6}}: With thanks to Luke, one of my long-suffering PhD students, for ‘volunteering’ to do some of this.

{{7}}: Rather than being eaten by ants, or blown away by a gust of wind.

{{8}}: With one outlier dropping almost 750 … eek!

{{9}}: I’m not suggesting they can discriminate between drifting bees carrying phoretic mites and those that are unencumbered, just that they are better at preventing ‘foreign’ bees from accessing the hive.

{{10}}: I’m a big fan of local bees, but if there are none they have to be introduced. Mine were from ~40 miles away, rather than a ‘factory (bee) farm’ in Cyprus, Greece or Italy.

{{11}}: Almost at the same latitude ~56ish°N.

{{12}}: Something else!

{{13}}: That really needs copious amounts of hot tea and homemade cakes.

{{14}}: If your investment portfolio includes lots of draughty church halls and cold community centres I’d recommend selling promptly.

{{15}}: Up to three frames from the strong ones.

{{16}}: Though, let’s be honest, does anyone not appreciate being given a jar of local honey?

Join the discussion ...