Bee shed musings

It’s the end of our third season using a bee shed, and the end of the first season using the ‘new and improved’ bee shed mark 2.

What’s worked and what hasn’t?

Why keep bees in a shed at all?

A bee hive provides a secure and weatherproof container to protect the colony {{1}}. Why then keep bee hives inside a building, like the bee shed?

Beekeeping, of necessity, involves regular inspections at 7-10 day intervals throughout the main part of the season. These inspections involve opening the hive and checking for disease, for evidence that the colony is developing as expected {{2}}, for adequate stores and space, and for for the telltale signs that the colony is thinking of swarming.

Since these inspections involve opening the hive the weather needs to be at least half-decent. Heavy rain, low temperatures and cold winds make it a less than pleasant experience – for the bees and for the beekeeper.

That’s not a problem if you have the luxury of being able to pick and choose days with benign conditions to inspect the colony.

But we don’t have that luxury.

The hives in the shed are used for research into the viruses (deformed wing virus and chronic bee paralysis virus) that are the major threats to colony health. Although we don’t conduct experiments in these hives we do use them as a regular source of larvae, pupae and workers for experiments in the laboratory {{3}}.

We therefore must be able to open and work in the hives:

- very early in the season

- very late in the season – we’re still harvesting brood as I write this in early November

- irrespective of the weather at particular times and/or days of the week

This is the east coast of Scotland. If it’s chucking it down with rain, blowing a hoolie {{4}}, really cold or a combination of these (not unusual), then not only is it unpleasant for the beekeeper, but it’s also unpleasant for the bees …

… and they let us know about it.

The bee shed

To protect the bees and the beekeeper we’ve built a shed to accommodate standard National hives, connected to the outside with simple tunnels.

From the outside it looks like a shed.

From the inside it looks like an apiary with wooden walls and less light {{5}}.

Details of the first shed and its successor are posted elsewhere. The current shed is 16 x 8 feet and houses up to seven full colonies arranged along the south-facing wall.

There are windows along the entire length of this wall of the shed, sufficient storage space for dozens of spare supers, brood boxes, floors, the hivebarrow and a couple of hundred kilograms of fondant.

Hives are all arranged ‘warm way’ on a single full-length stand and inspected from the rear.

How does all this work in practice?

Space

The shed is probably still too small 🙁

Once all of that lovely storage space is in use there’s a relatively narrow passageway between the hives and the stacks of supers and fondant. For a lone beekeeper this isn’t an issue. For training purposes, or with multiple people working at once, it’s distinctly cramped.

Inspections involve lots of walking back and forwards to the door (see below) and this would be made much easier by:

- not storing spare supers, fondant, broods and the wheelbarrow in the shed

- only allowing very thin people with no concept of ‘personal space’ to use the shed

- having a much wider shed

Of these, the last option is probably the most realistic.

I’ve recently been asked for comments about using a shed for a school beekeeping association. Since this is likely to involve an element of training, with several trainees huddling around the hive, my advice would be:

- reduce the number of hives to a maximum of three in a 16 foot long shed, each on individual stands with space to access the hive from both behind and the sides

- buy a wider shed or store all those ‘essential’ spares elsewhere

Lighting

The shed has a solar powered LED lighting system running off a 100Ah ‘leisure’ battery. There are six of the highest power LED lights available (~120W equivalents … each ~700 lumens {{6}}) immediately above the hives.

The lighting is great. It makes working in the shed ‘off grid’ in the evenings or on dull and dingy days much easier.

However, on a bright day this lighting is insignificant when compared to the light streaming in through the windows.

But, whatever the weather, the lighting inside the shed is still less than optimal when you’re looking for eggs or day-old larvae.

Perhaps it’s my increasingly poor eyesight but I find myself nipping out of the shed door to inspect frames for eggs or tiny larvae. It’s so much easier with the sun coming over your shoulder and angling the frame to illuminate the base of the cells.

I’m planning to rearrange the lighting so it runs down the centre of the shed rather than being directly over the hives. That way it will be ‘over the shoulder’ when inspecting frames.

And if that doesn’t work the only option will be to invest in banks of LEDs … or glasses 😎

On a brighter note – no pun intended – the solar panel, charge controller and large lead acid battery, coupled with a door ‘on when open’ switch, have worked flawlessly.

Windows

The shed windows are formed from overlapping sheets of perspex.

The weather cannot get in, but bees can easily get out. They crawl up the large pane, under the overlapping pane, and then fly from the 2cm slot between that and the top of the window aperture. It’s a simple and highly-effective solution to emptying a shed of bees after inspections.

But I’ve discovered this year that wasps can learn to enter the shed via the windows.

2018 was a bad year for wasps. I lost a nuc and a queenless (actually a requeening) colony to robbing by wasps in this apiary. At some point during the season wasps learnt to access the shed via the window ‘slot’ and for several weeks we were plagued with them. I think we were partly to blame because we had some comb offcuts in a waste bin that wasn’t properly sealed. Once the wasps had discovered this source of honey/nectar they were very persistent … as wasps are.

This hasn’t been a problem in previous years so I’m hoping that improved apiary hygiene will prevent it being an issue next year.

No smoke …

Our bees are calm and well behaved. However, we still use a limited amount of smoke during inspections {{7}}. Leaving a well-lit smoker standing next to the hive throughout the inspection is a guaranteed way to become as kippered as an Arbroath smokie {{8}}. It doesn’t take long to fill the shed with smoke.

I therefore leave the smoker standing ‘ready for action’ just outside the shed door. It’s easy (assuming the shed isn’t full of people) to take a couple of steps to the door, recover the smoker, give them a gentle puff, return the smoker and continue.

… without fire

Sheds are made of wood. Beehives are wood or polystyrene. The stacks of spare supers and broods are full of wax-laden frames.

All this has the potential to burn very well indeed.

I’m therefore very careful to leave the smoker, securely plugged with grass, on a non-flammable surface. The wire of a spare open mesh floor is ideal for this.

Colony management

Routine colony management – inspections, supering, swarm prevention and control, Varroa treatment – work just as well in the bee shed as outside.

There are a few limitations of course.

Vertical splits for making increase or swarm control aren’t an option as it’s not possible (or at least not practical) to provide an upper entrance with access to the outside world.

Similarly, space adjacent to a hive is limited so a classic Pagden artificial swarm may not be possible {{9}}. Instead I usually use the nucleus method of swarm control – removing the old queen and a frame of brood and stores to make a nuc, then leaving the hive in the shed to requeen.

Benefits for the bees

I suspect that the main beneficiaries of the bee shed are the beekeepers, not the bees. However, colonies do appear to do well in the shed.

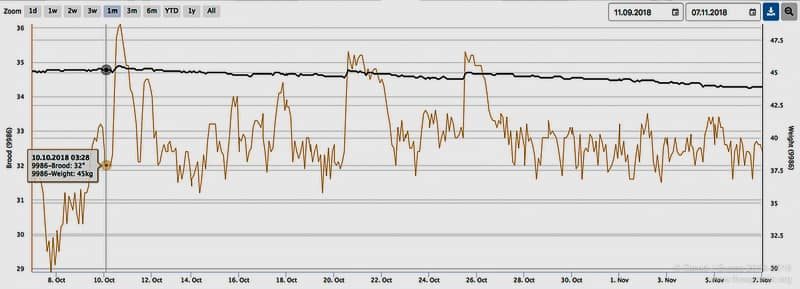

The impression is that brood rearing starts earlier in the season and ends later, though formally we have yet to demonstrate this. We now have some hives inside and outside the shed fitted with Arnia monitors. With these we can monitor brood temperature, humidity, hive weight and activity.

Brood temperature is an indicator of brood rearing, with temperatures around 33°C showing that the queen is laying. By monitoring colonies over the winter we expect to be able to determine when brood rearing stops and starts again {{10}} and, by comparison, whether the season is effectively ‘longer’ for bees within the shed.

But it’ll be months until we’ll see this sort of entrance activity again …

{{1}}: And if yours don’t, they should!

{{2}}: Which might, towards the end of the season, mean the levels of sealed and unsealed brood are decreasing as expected.

{{3}}: Where we can control the environment much more accurately.

{{4}}: A relatively new word, first recorded less than 30 years ago, and meaning very windy … probably from the Orkney hoolan which – in turn – has origins in Old Icelandic and Faroese ýlan meaning howling or wailing.

{{5}}: And less rain and wind.

{{6}}: You can get much brighter LED’s, but not that conveniently fit into standard ES- or bayonet-type ceiling mounts.

{{7}}: Perhaps a bit more than necessary as some of the beekeepers working with the hives are relatively inexperienced.

{{8}}: A confusing description … kippered refers to the act of cleaning, salting and smoking herring, whereas an Arbroath smokie refers to a smoked haddock … but you get the idea.

{{9}}: However, if space elsewhere in the shed is available these work very well.

{{10}}: And therefore the optimal time to treat with dribbled Api-Bioxal for the winter Varroa management.

Join the discussion ...