Broodless?

Synopsis : The colony needs to be broodless for effective oxalic acid treatment in winter. You might be surprised at how early in the winter this broodless period can be (if there is one). How can you easily determine whether the colony is broodless?

Introduction

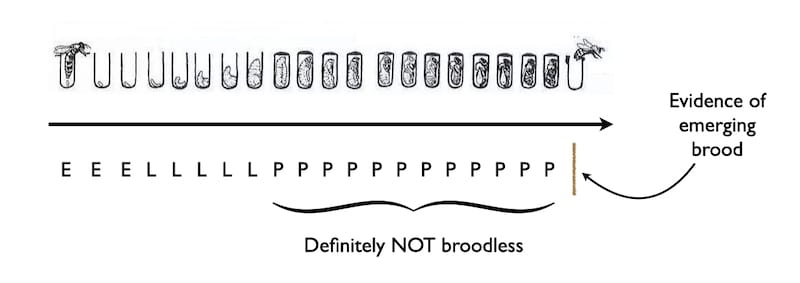

In late spring or early summer a broodless colony is a cause for concern. Has the colony swarmed? Have you killed the queen? Since worker brood takes 21 days from egg to emergence, a broodless colony has gone 3 weeks without any eggs being laid.

You’re right to be concerned about the queen.

Of course, since you’ve been inspecting the hive on a 7-10 day rotation, you noticed the absence of eggs a fortnight ago, so you’re well on your way to knowing what the problem is, and therefore being able to solve it 😉 .

But in late autumn or early winter a broodless colony is not a cause for concern.

It’s an opportunity.

In my view it’s a highly desirable state for the colony to be in.

If the colony is broodless then the ectoparasitic Varroa mites cannot be hiding away under the cappings, gorging themselves on developing pupae and indulging in their – frankly repellent – incestuous reproduction.

Urgh!

Instead the mites will all be riding around the colony on relatively young workers (and in winter, physiologically all the workers in the hive are ‘young’, irrespective of their age) in what is incorrectly termed the phoretic stage of their life cycle.

This is incorrect as phoresy means “carried on the body of another organism without being parasitic” … and these mites are not just being carried around, they’re also feeding on the worker bees.

You can read all about phoretic mites, their diet and their repulsive reproductive habits in previous posts.

What is the opportunity?

A broodless colony in the winter is an opportunity because phoretic mites (whether misnamed or not) are very easy to kill because they’re not protected by the wax capping covering the sealed brood.

And today’s post is all about identifying when the colony is broodless.

Discard your calendar

I’ve said it before {{1}} … the activities of the colony (swarming, nectar gathering, broodlessness {{2}} ) are not determined by the calendar.

Instead they’re determined by the environment. This covers everything from the available forage to the climate and recent weather {{3}}.

And the environment changes. It changes from year to year in a single location – an early spring, a late summer – and it differs between locations on the same calendar date.

All of which means that, although you can develop a pretty good idea of when you need to intervene or manage things – like adding supers, or conducting swarm control – these are reactive responses to the state of the colony, rather than proactive actions applied because it’s the 9th of May {{4}}.

And exactly the same thing applies to determining when the colony is broodless in the winter. Over the last 6 years I’ve had colonies that are broodless sometime between between mid October and mid/late December. They’re not broodless for this entire period, but they are for some weeks starting from about mid-October and ending sometime around Christmas.

Actually, to be a little more precise, I generally know when they start to be broodless, but I rarely monitor when they stop being broodless, not least because it’s a more difficult thing to determine (as will become clear).

Don’t wait until Christmas

A broodless colony is an opportunity because the phoretic mites can easily be killed by a single application of oxalic acid.

Many beekeepers treat their colonies with oxalic acid between Christmas and New Year.

It was how they were taught when they started beekeeping, it’s convenient because it’s a holiday period, it’s a great excuse to escape to the apiary and avoid another bellyful of cold cuts followed by mince pies (or the inlaws {{5}} ) and because it’s ‘midwinter’.

But, my experience suggests this is generally too late in the year. The colony is often already rearing brood by the time you’ve eaten your first dozen mince pies.

If you’re going to go to the trouble of treating your colonies with oxalic acid, it’s worth making the effort to apply it to achieve maximum efficacy {{6}}.

I’m probably treating my colonies with oxalic acid in 8-9 days time. The queens have stopped laying and there was very little sealed brood present in the colonies I briefly checked on Monday this week. The sealed brood will have all emerged by the end of next week.

It’s worth making plans now to determine when your colonies are broodless. Don’t just assume sometime between Christmas and New Year ’will be OK’.

But it’s too early now for them to be broodless … or to treat with oxalic acid

If your colonies are going to go through a broodless period this winter {{7}} it’s more likely to be earlier rather than later.

Why?

Because if the colonies had a long broodless period stretching into mid-January or later it’s unlikely they’ll build up strongly enough to swarm … and since swarming is honey bee reproduction, it’s a powerful evolutionary and selective pressure.

Colonies that start rearing brood early, perhaps as early as the winter solstice, are more likely to build up strongly, and therefore are more likely to swarm, so propagating the genes for early brood rearing.

But surely it would be better to treat with oxalic acid towards the end of the winter?

Mites do not reproduce during the misnamed phoretic stage of the life cycle. Therefore, aside from those mites lost (hopefully through the open mesh floor) due to allogrooming, or that just die {{8}}, there will be no more mites later in the broodless period than at the beginning.

Since the mites are going to be feeding on adult workers (which is probably detrimental to those workers), and because it’s easier to detect the onset of broodlessness (see below), it makes sense to treat earlier rather than later.

Your bees will thank you for it 😉 .

How to detect the absence of brood

Tricky … how do you detect if something is not present?

I think the only way you can be certain is to conduct a full hive inspection, checking each side of every frame for the presence of sealed brood.

Perhaps not the ideal conditions for a full hive inspection

But I’m not suggesting you do that.

It’s a highly intrusive thing to do to a colony in the winter. It involves cracking open the propolis seal to the crownboard, prising apart the frames and splitting up the winter cluster.

On a warm winter day that’s a disruptive process and the bees will show their appreciation 🙁 . On a cold winter day, particularly if you’re a bit slow checking the frames (remember, the bees will appear semi-torpid and will be tightly packed around any sealed brood present, making it difficult to see), it could threaten the survival of the colony.

And don’t even think about doing it if it’s snowing 🙁 .

Even after reassembling the hive the colony is likely to suffer … the broken propolis seals will let in draughts, the colony will have to use valuable energy to reposition themselves.

A quick peek

I have looked in colonies for brood in the winter. However, I don’t routinely do this.

Now, in mid/late autumn the temperature is a bit warmer and it’s less disruptive. I checked half a dozen on Sunday/Monday. It was about 11°C with rain threatening. I had to open the boxes to retrieve the Apivar strips anyway after the 9-10 week treatment period.

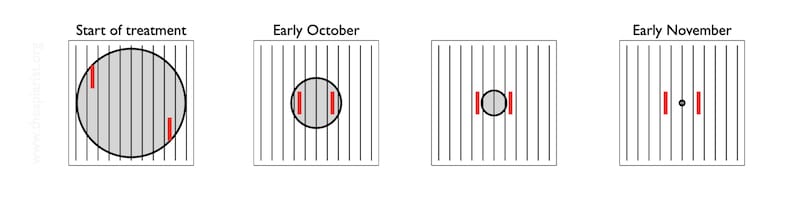

I had repositioned the Apivar strips about a month ago, moving them in from the outside frames to the edges of the shrinking brood nest. By then – early October – most of the strips were separated by just 3 or 4 frames.

The flanking frames were all jam packed with stores. The fondant blocks were long-gone and the bees had probably also supplemented the stores with some nectar from the ivy.

Over the last month the brood nest continued to shrink, but it won’t have moved somewhere else in the hive … it will still be somewhere between the Apivar strips, and about half way is as good a place as any to start.

So, having removed the crownboard and the dummy board, I just prise apart the frames to release the Apivar strips and then quickly look at the central frame between them. If there’s no sealed brood there, and you can usually also have a look at the inner faces of the flanking frames down the ‘gap’ you’ve opened, then the colony is probably broodless.

It takes 45-60 seconds at most.

It’s worth noting that my diagram shows the broodnest located centrally in the hive. It usually isn’t. It’s often closer to the hive entrance and/or (in poly boxes) near the well insulated sidewall of the hive.

Hive debris

But you don’t need to go rummaging through the brood box to determine whether the colony is broodless (though – as noted earlier – it is the probably the only was you can be certain there’s no brood present).

The cappings on sealed brood are usually described as being ‘biscuit-coloured’.

‘Biscuit-coloured’ is used because all beekeepers are very familiar with digestive biscuits (usually consumed in draughty church halls). If ‘biscuit-coloured’ made you instead think of Fox’s Party Rings then either your beekeeping association has too much money, or you have young children.

Sorry to disappoint you … think ‘digestives’ 😉 .

The cappings are that colour because the bees mix wax and pollen to make them air-permeable. If they weren’t the developing pupa wouldn’t be able to breathe.

And when the developed worker emerges from the cell the wax capping is nibbled away and the ‘crumbs’ (more biscuity references) drop down through the cluster to eventually land on the hive floor.

Where they’re totally invisible to the beekeeper 🙁 .

Unless it’s an open mesh floor … in which case the crumbs drop through the mesh to land on the ground where they’ll soon get lost in the grass, carried off by ants or blown away 🙁 .

It should therefore be obvious that if you want detect the presence of brood emerging you need to have a clean tray underneath the open mesh floor (OMF).

Open mesh floors and Correx boards

Most open mesh floors have a provision to insert a Correx (or similar) board underneath the mesh. There are good and bad implementations of this.

Poor designs have a large gap between the mesh and the Correx board, with no sealing around the edges {{9}}. Consequently, it’s draughty and stuff that lands on the board gets blown about (or even blown away).

Good designs – like the outstanding cedar floors Pete Little used to make – have a close-fitting wooden tray on which the Correx board is placed. The tray slides underneath the open mesh floor and seals the area from draughts {{10}}.

Not only does this mean that the biscuity-coloured crumbs stay where they fall, it also means that this type of floor is perfect when treating the colony with vaporised oxalic acid. Almost none escapes, meaning less chance of being exposed to the unpleasant vapours if you’re the beekeeper, and more chance of being exposed to the unpleasant vapours if you’re a mite 😉 .

Since the primary purpose of these Correx trays is to determine the numbers of mites that drop from the colony, either naturally or during treatment, it makes sense if they are pale coloured. It’s also helpful if they are gridded as this makes counting mites easier.

And, with a tray in situ for a 2-3 days you can quickly get an idea whether there is brood being uncapped.

Reading the runes

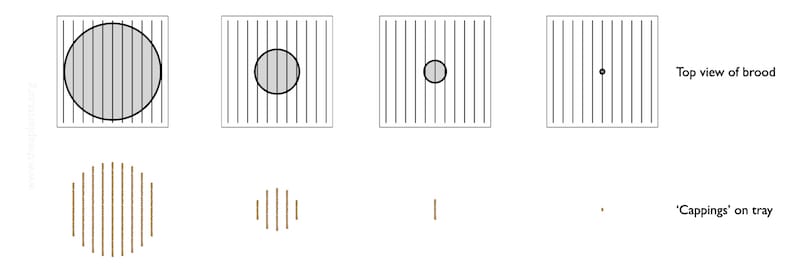

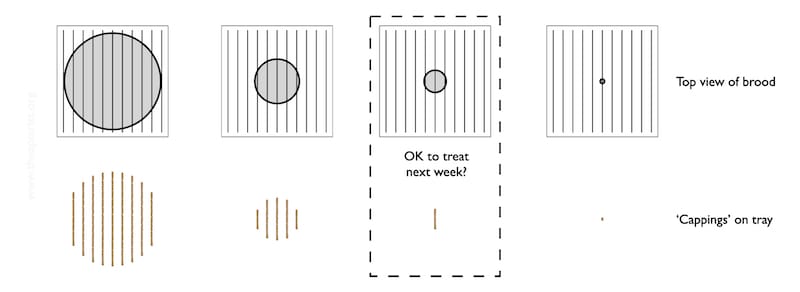

The diagram below shows a schematic of the colony (top row) and the general appearance of debris on the Varroa tray (bottom row).

It’s all rather stylised.

The brood nest – the grey central circle is unlikely to be circular, or central {{11}}.

Imagine that the lower row of images represent the pattern of the cappings that have fallen onto the tray over at least 2-3 days.

As the brood nest shrinks, the area covered by the biscuit-coloured cappings is reduced. At some point it is probably little more than one rather short stripe, indicating small amounts of brood emerging on two facing frames.

Let’s assume you place the tray under the open mesh floor and see that single, short bar of biscuity crumbs (highlighted above). There’s almost nothing there.

Do you assume that it will be OK to treat them with oxalic acid the following week?

Not so fast!

With just a single observation there’s a danger that you could be seeing the first brood emerging when there’s lots more still capped on adjacent frames.

It’s unlikely – particularly in winter – but it is a possibility.

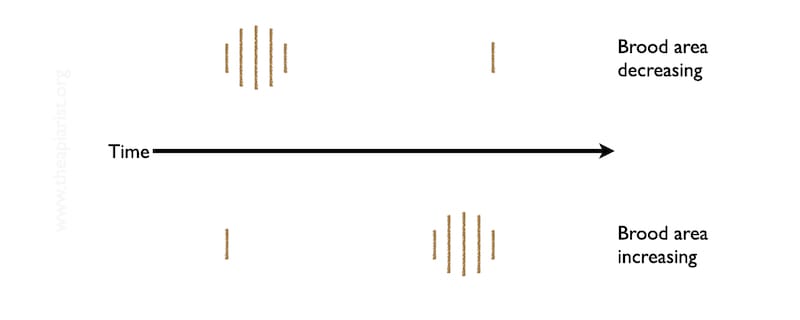

Far better is to make a series of observations and record the trajectory of cappings production. Is it decreasing or is it increasing?

With a couple of observations 10-12 days apart you’ll have a much better idea of whether the brood area is decreasing over time, or increasing. Repeated observations every 10-12 days will give you a much better idea of what’s going on.

Developing brood is sealed for ~12 days. Therefore, if brood rearing is starting, the first cappings that appear on the Varroa tray are only a small proportion of the total sealed brood in the colony.

Of course, in winter, the laying rate of the queen is much reduced. Let’s assume she’s steadily laying just 50 eggs per day i.e. about 12.5 cm2. By the time the first cappings appear on the Varroa tray (as the first 50 workers emerge) there will be another 600 developing workers occupying capped cells … and the worry is that they’re occupying those cells with a Varroa mite.

The cessation of brood rearing

In contrast, if there’s brood in the colony but the queen is slowing down and eventually stops egg laying, with repeated observations {{12}} the amount and coverage of the biscuit-coloured cappings will reduce and eventually disappear.

At that point you can be reasonably confident that there is no more sealed brood in the colony and, therefore, that it’s an appropriate time to treat with oxalic acid.

In this instance – and unusually – absence of evidence is evidence of absence 🙂 .

But my bees are never broodless in the winter

All of the above still applies, with the caveat that rather than looking for the absence of any yummy-looking biscuity crumbs on the tray, you are instead looking for the time that they cover the minimal area.

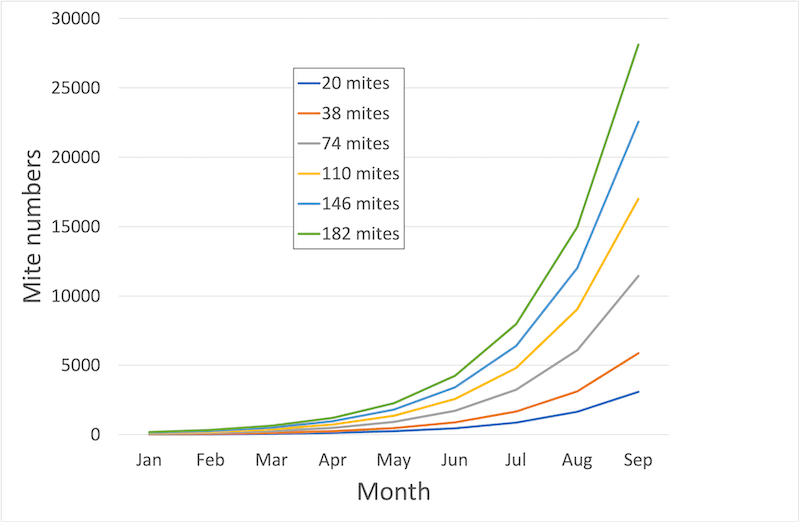

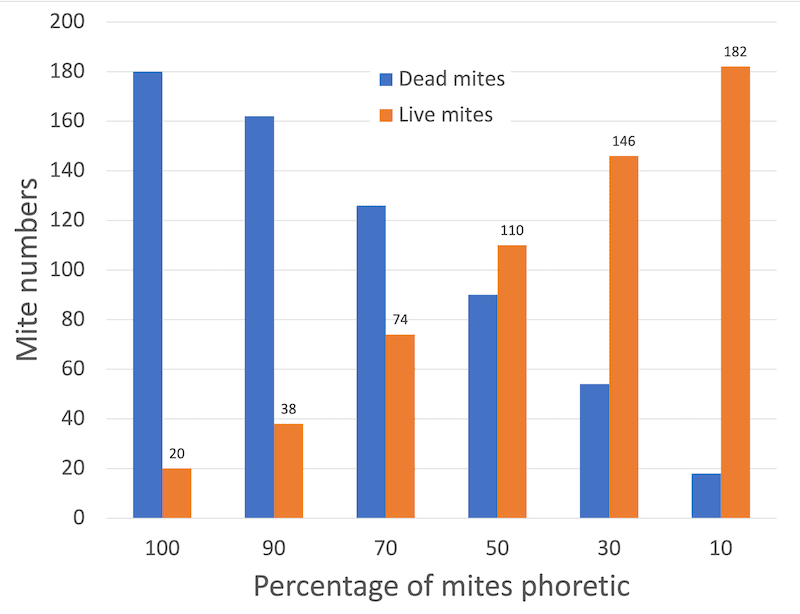

If the colony is never broodless in winter it still makes sense to treat with oxalic acid when the brood is at the lowest level (refer back to the first graph in this post).

At that time the smallest number of mites are likely to be occupying capped cells.

However, this assumption is incorrect if the small number of cells are very heavily parasitised, with multiple mites occupying a single sealed cell. This can happen – at least in summer – in heavily mite infested hives. I’ve seen 12-16 mites in some cells and Vincent Poulin reported seeing 26 in one cell in a recent comment.

Urgh! (again)

I’m not aware of any data on infestation levels of cells in winter when brood levels are low, though I suspect this type of multiple occupancy is unlikely to occur (assuming viable mite numbers are correspondingly low). I’d be delighted if any readers have measured mites per cell in the winter, or know of a publication in which it’s reported {{13}}.

This isn’t an exact science

What I’ve described above sounds all rather clinical and precise.

It isn’t.

Draughts blow the cappings about on the tray. The queen’s egg laying varies from day to day, and can stop and start in response to low temperatures or goodness-knows-what-else. The pattern of cappings is sometimes rather difficult to discern. Some uncapped stores can have confoundingly dark cappings etc.

But it is worth trying to work out what’s going on in the box to maximise the chances that the winter oxalic acid treatment is applied at the time when it will have the greatest effect on the mite population.

By minimising your mite levels in winter you’re giving your bees the very best start to the season ahead.

Unrestricted mite replication – the more you start with the more you end up with (click image for more details)

The fewer mites you have at the start of the season, the longer it takes for dangerously high mite levels (i.e. over 1000 according to the National Bee Unit) to develop. Therefore, by reducing your mite levels in the next few weeks you are increasing your chances that the colony will be able to rear large numbers of healthy winter bees for next winter.

That sounds to me like a good return on the effort of making a few trips to the apiary in November and early December …

{{1}}: And I’ll no doubt say it again … I’m nothing if not repetitive.

{{2}}: Is that a word? Auto-correct wanted to make it bloodlessness, so I’ll assume it is. You know what I mean anyway.

{{3}}: In addition, the strain of bees and age of the queen can also influence things.

{{4}}: Or whenever …

{{5}}: Visiting that is, not part of the diet.

{{6}}: Of course, the same sentiment applies to any treatment applied to the colony … use them properly, at the right time, the right temperature and for the correct duration.

{{7}}: And not all do, particularly in the more balmy southern parts of the UK.

{{8}}: Hurrah!

{{9}}: Abelo floors certainly used to be particularly poorly designed.

{{10}}: Infuriatingly I’ve got about a dozen of these floors and not a single really good picture showing how well-fitting the tray is. Take my word for it … I’ve not seen better.

{{11}}: Or grey for that matter

{{12}}: Each time placing a clean tray in for sufficient time to see the cappings that fall through the OMF.

{{13}}: Send me an email using the link in the footer.

Join the discussion ...