More droning on ...

Synopsis : Drones are now being evicted from colonies. How and why does a honey bee colony regulate drone numbers?

Introduction

Over the course of the last eight years posts on The Apiarist have got longer. This year, posts are now five times the length of the 2014 average. I’ve written – and hopefully, you’ll have already read – more words this year than are in The Hobbit.

If this continues until the end of the year we’ll have exceeded the word count in Tolkien’s The Two Towers.

This is probably unsustainable {{1}}.

The increase is explained in part by the complexity of some topics. It’s compounded by the need to provide some contextual information … and by my prolixity {{2}}. The latter is unavoidable, the former is probably necessary, not least because of the significant churn in new beekeepers.

A topic needs to be introduced, explained, justified and concluded.

Without this contextual information a post on oxalic acid trickling could be just:

5 ml of 3.2% w/v per seam when they’re broodless.

And where’s the fun in reading that?

Or writing it?

Furthermore, it’s probably of little use to a beginner who might not know what w/v means. Or what a seam is … or for that matter why being broodless is critical.

Keeping it topical

To maximise the income from site advertising I need to keep readers returning. This means the choice of topics should be important.

However, although some topics are chosen because they’re key concepts in the art and science of beekeeping, the majority are picked simply because I find them interesting.

And this week is one of the latter as I’m going to be droning on about … drones.

Specifically about drone numbers in the colony.

This was prompted by seeing the first drones of the season turfed out of the hive.

Seeing this coincided with me discovering an interesting paper on how the queen’s laying history influences whether she produces drone or worker brood. This, inevitably, led me to other papers on drone production and discussions of how the colony controls drone numbers {{3}}.

Drones are topical now because their days in your colonies are limited.

Already the colony will be producing significantly less drone brood than three months ago. The drones the colony has already produced will still {{4}} be flying strongly on good days.

However, when in the hive they will be being increasingly harassed by the workers.

If you open a colony very gently in the next few weeks {{5}} you might find the corners of the box contain high numbers of drones. The photo above was taken in late August and I’ve seen it several times late in the season. My interpretation is that it’s the only location in the hive in which drones can escape harassment by the workers.

Drone eviction

Drones ‘cost’ the colony a lot to maintain. A drone consumes about four times the amount of food than a worker (Winston, 1987). Therefore, once the fitness benefit of keeping drones falls below the expected costs needed to keep them they become ’surplus to requirements’. At this point the workers turf them out of the hive.

Evicted drones cannot feed themselves, so they perish.

It’s a tough life.

Interestingly, workers preferentially evict old drones. Presumably younger drones are more likely to fly strongly and mate with a virgin queen. Additionally, sperm viability in older drones is reduced, so their genes (and therefore those of the colony) are less likely to be passed on.

This ‘cost’ of maintaining drones is influenced by both the colony and the environment. For example, queenright colonies (which, by definition, have less need for drones) evict more drones than queenless colonies in the autumn, as nectar becomes limiting.

Although most beekeepers associate drone eviction with late summer/early autumn it also occurs when nectar is in short supply e.g. during the ‘June gap’.

It has also been suggested that drone eviction rates are related to colony size. Small queenright nucs, which have less need for drones, are more likely to evict than a full colony.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about drone eviction. For example, since drones tend to accumulate in queenless colonies, do these preferentially evict related drones to maintain potential genetic diversity in the population? {{6}}

Hannibal the cannibal

Allowing an unfertilised egg to hatch, feeding the larva, incubating the pupa to emergence and then maintaining the resulting drone is a waste of resources if conditions are not appropriate. For example, doing this during a nectar dearth – particularly when drones are unlikely to be required for mating – makes no sense {{7}}.

Therefore, in early spring and late autumn, workers cannibalise developing drone larvae. Effectively they are recycling colony resources. They preferentially cannibalise young larvae rather than older larvae. This makes sense as young larvae are going to need more food to reach maturity.

As above, queenless colonies cannibalise less queen-laid {{8}} drone larvae than queenright colonies.

In addition, some studies have shown that colonies with abundant adult drones cannibalise a greater proportion of developing drones. Again, this makes reasonable sense. Why rear more if you’ve got enough already?

However, to me it makes ‘reasonable’, but not ‘complete’ sense. Drones being reared as larvae are genetically related to the colony, adult drones may well not be. Drones that have drifted in from adjacent hives may therefore reduce the likelihood of the colony passing on its genes under environmental conditions which favour larval destruction but not eviction of adult drones.

Someone needs to look into this in a bit more detail 😉 .

There are lots of other aspects of larval cannibalism that are not understood. For example, how do workers discriminate between drone and worker larvae? Can they – as the queen can – measure the cell dimensions? Drone and worker brood pheromones differ from day 3 or 4. This seems a bit late to account for the cannibalisation of young larvae?

The influence of the queen

Since workers may cannibalise developing larvae {{9}} at different rates (drone vs. worker) it’s necessary to measure the colony’s egg sex allocation to see how the queen may influence drone numbers.

Only a few studies have done this …

There are experiments that suggest (they’re not definitive) that queens in continuously fed colonies lay more drone eggs in spring and summer than in autumn. This implies that day length or temperature may influence the queen, but it could also be a response to colony strength i.e. the queen lays more unfertilised eggs in a colony increasing in size, than in one decreasing.

In addition – and this is where I started down this rabbit hole in the first place – the egg laying history of the queen influences her current egg laying activity.

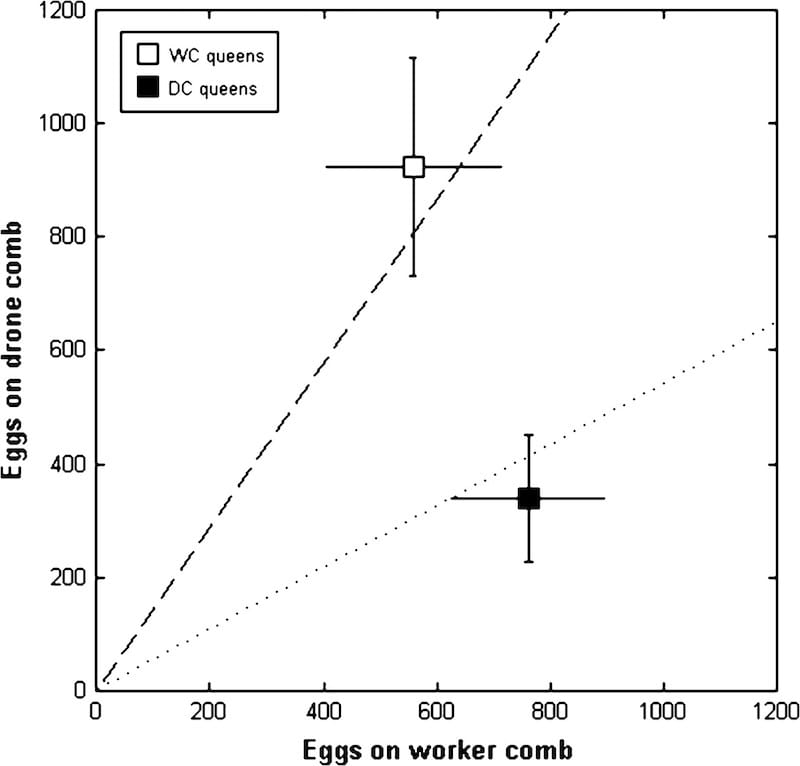

This easy-to-understand study was conducted by Katie Wharton and colleagues (Wharton, 2007). They confined queens for a period on either drone (DC) or worker comb (WC) – ensuring the queen could only lay drone or worker eggs for 4 days. They then transferred the queens to frames containing a 50:50 mix of drone and worker comb and recorded the amount of drone or worker eggs laid over 24 hours.

There was a marked difference in the egg laying activity of the DC or WC queens when given the choice of laying drone or worker eggs. Although both the DC and WC queens laid similar amounts of worker eggs, the WC queens produced significantly more drone eggs as well.

Egg laying history or drone brood quantification?

This is a good study. The authors controlled for a variety of factors including season, colony size and food availability.

They additionally excluded the possibility that the egg laying activity of the queen was influenced by preferential cleaning of particular cells types by the workers, or by the workers backfilling certain cell types with nectar.

Finally, Wharton and colleagues allowed the colony to rear the eggs laid to pupation. The bias already observed was retained i.e. colonies headed by WC queens reared significantly more drone pupae than those headed by DC queens. The workers did not ‘correct’ the negative feedback exhibited by the WC queen, for example by preferentially cannibalising drone brood.

Although I termed this the ‘egg laying history’ of the queen a few paragraphs ago there is another interpretation.

The worker or drone comb already laid up by the queen – during the 4 day confinement period – remained in the colony. It’s therefore possible that the egg laying activity of the queen was influenced by the amount of drone brood already present in the colony.

Either explanation is intriguing.

How does the queen ‘count’ the number of drone or worker eggs she’s laid in the recent past? Alternatively, how does she quantify the amount of drone brood in the colony?

But what about the workers?

The Wharton study largely excluded the possibility that there was preferential cleaning of drone or worker cells by the workers in the hive. In fact, earlier studies have indicated that cell cleaning continues almost constantly and workers were equally likely to clean worker or drone cells.

The Wharton study also addressed – and excluded – the possibility that differences in the backfilling of drone or worker cells might influence egg laying.

However, it’s not understood what determines whether drone cells get backfilled with nectar by workers. My colonies are starting to do this now. Do the workers fill drone cells with nectar because the queen hasn’t laid in these cells or because they only backfill drone cells late in the season?

The former suggests that there is some sort of competition between the egg laying activity by the queen and nectar storage by workers. In contrast, the latter suggests that there are environmental triggers that influence this worker activity.

Or both … of course 😉 .

Comb building

In contrast to some of the studies outlined above, comb building is easy to monitor and – perhaps consequently {{10}} – has been well studied.

I’ve already discussed comb building in a recent post about queenless colonies. These preferentially build drone comb (Smith, 2018).

What else influences drone comb production?

Probably the two strongest determinants are the amount of drone comb already in the nest and the season.

Drone comb production is reduced in colonies that already contain lots of drone comb. Many beekeepers never observe this as they only use frames containing worker foundation. The workers squeeze in little patches of drone comb – often in the corners of the frame – but it never exceeds 5% of the total.

In contrast, natural nests contain 15-20% drone comb. That’s equivalent to two full frames in a National-sized hive. Once drone comb approaches this level a negative feedback loop operates and the workers build less drone comb. The negative influence of this drone comb (on building more drone comb) is enhanced if the comb contains drone brood.

Colonies drawing comb now (and certainly in the next month or two) will build worker comb. Some beekeepers exploit this to get lovely new worker frames drawn – nucs are particularly good at this {{11}}. In contrast, drone comb is drawn in spring and early summer. The season – presumably day length and temperature – therefore influences drone comb production, and hence drone production.

A thousand words

Well, nearer 2000.

As we near the end of the season we start to see drones evicted from our colonies. It’s interesting to think about the interplay of events that resulted in the colony producing those drones in the first place … and how and why the colony regulates drone production throughout the season.

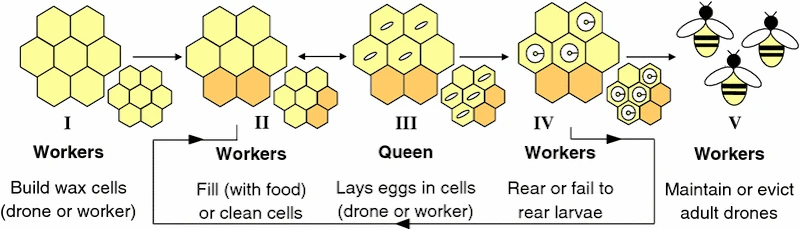

Wharton (2007) neatly summarised the five stages from comb building to adult drone eviction.

I’ve dealt with these in reverse order because that was the best fit with the photo of the dead drone on the landing board that I started with.

There’s a lot we still don’t understand about the regulation of drone numbers. In particular, I think the majority of studies have ignored the influence of adult drone numbers on any of five stages illustrated above.

This is an important omission as drones move more or less freely between hives. That means that adult drones may well be genetically unrelated to the colony.

Perhaps this means that adult drones do not influence drone production? After all, if they did negatively influence drone production – as suggested above – it would potentially limit the ability of a colony to reproduce its genes. Evolutionarily this doesn’t make sense (at least, to me).

There are a couple of studies that have tried to determine the influence of adult drones, but they have produced conflicting results. Rinderer (1985) added drones to a colony which consequently reduced drone brood production. However, Henderson (1994) did the opposite and showed that removal of adult drones had no effect on drone brood production.

There’s clearly lots more to do …

Notes

I wrote this late on Thursday night. While doing so I watched the page views of my four year old post on Mad honey go ‘off the scale’ (which for a beekeeping site means hundreds of views per hour). The interest wasn’t sparked by my erudite description of grayanotoxin intoxication. Instead it was related to a video of a ‘stoned’ Turkish brown bear cub rescued after eating honey produced from rhododendron nectar.

It’s now abundantly clear that if I want to maintain my outrageous advertising income I should probably write more about hallucinogenic honey and less about the evolutionary subtleties of honey bee sex ratio determination.

That’ll teach me 😉

References

Boes, K.E. (2010) ‘Honeybee colony drone production and maintenance in accordance with environmental factors: an interplay of queen and worker decisions’, Insectes Sociaux, 57(1), pp. 1–9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-009-0046-9.

Henderson, C.E. (1994) ‘Influence of the presence of adult drones on the further production of drones in honey bee (Apis mellifera L) colonies’, Apidologie, 25(1), pp. 31–37. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:19940104.

Rinderer, T.E. et al. (1985) ‘Male Reproductive Parasitism: A Factor in the Africanization of European Honey-Bee Populations’, Science, 228(4703), pp. 1119–1121. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.228.4703.1119.

Smith, M.L. (2018) ‘Queenless honey bees build infrastructure for direct reproduction until their new queen proves her worth’, Evolution, 72(12), pp. 2810–2817. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13628.

Wharton, K.E. et al. (2007) ‘The honeybee queen influences the regulation of colony drone production’, Behavioral Ecology, 18(6), pp. 1092–1099. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arm086.

Winston, M.L. (1987) The Biology of the Honey Bee. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

{{1}}: More on this in the future.

{{2}}: Verbosity isn’t the right word here. Prolixity (to me at least) means tediously verbose. There’s a difference.

{{3}}: See Boes (2018) for a good overview.

{{4}}: Assuming they’ve not ’scored’ yet (and/or died trying).

{{5}}: Depending on how much of the season is still remaining at your latitude.

{{6}}: Not a simple question and confounded by the different distances drones and queens fly to mate.

{{7}}: And evolution is usually as logical as that famous pointy-eared Vulcan, Mr. Spock.

{{8}}: OK, that doesn’t seem to make sense. This was done by removing the queen under environmental conditions where drones were undesirable.

{{9}}: Or pupae, but that’s outside the scope of this post.

{{10}}: As scientists like doing easy experiments!

{{11}}: Colony size also influences drone comb production; swarms don’t produce drone comb for about 3 weeks and large swarms go on to produce more drone comb than small swarms.

Join the discussion ...