Foundationless frames redux

Synopsis : Foundation is getting more expensive. Try foundationless frames; save money and reduce miticide contamination in your hives.

Introduction

While preparing some minor updates for a talk this week {{1}} I had cause to look up the price of foundation.

Flippin’ heck!

Foundation is one of the beekeeping basics. It’s effectively a consumable item that you periodically have to replace … or more correctly you replace the frames containing new sheets of foundation. It is recommended that brood frames are replaced every three years; this means you should expect to replace 3-4 frames per season in a National hive.

Like other basics, such as eggs and pasta, the price of foundation is rising inexorably. The last stuff I bought – premium National wired worker deep – was about £13 from Thorne’s. I bought ~15 packets and it hurt.

It’s now £15.60 a packet (for 10 sheets) {{2}}. If it goes up much more I’ll have to trade in a kidney before visiting Brian at Thorne’s of Newburgh.

At £15.60 a packet, the foundation costs alone of frame replacement are ~£5.50/hive/year. You’ll need another 5-11 sheets per hive during the swarming season, depending how you do your swarm control, and yet more if you rear queens and sell nucs. This is worst case scenario of course, but it gives you an idea of the costs.

I run 20-25 colonies and estimate my foundation costs should be ~£350/annum. I actually spend well under half that because I use a lot of foundationless frames.

All beekeepers are mean like saving money. As it’s 6 years since I last wrote specifically about foundationless frames I thought it was time for an update … so here goes.

What is a foundationless frame?

The clue is in the name.

It’s a frame constructed without a sheet of foundation. Typically it will contain some guides (‘starter strips’) so the bees know where to start drawing comb, together with supports to be incorporated as the comb is drawn.

The frame itself is a standard brood or super frame, exactly the same as you would use with a sheet of foundation. You can purchase frames specifically designed to be used without foundation but I strongly recommend you don’t bother; at £23.60 for 10 they’re already more than standard first-quality brood frames {{3}}.

Freshly drawn foundationless comb … beautiful

What’s more, I also recommend you don’t bother buying first quality frames. The majority of my frames – and almost all the foundationless ones – are built using second quality frames purchased during the annual sales.

The most recent price I’ve seen for these second quality frames is £38.50 for 50 i.e. ~77p each. You can expect a few knots or splits, some of which are unrepairable. Use your judgement, if the lugs are weakened, use the top bar for firewood. Ditto if it’s badly warped. A dab of wood glue and a well aimed gimp pin will sort out most other problems. I usually find that ~2-3% are duds.

Construction

You start with a standard frame. I’ve described how I build these before. Remove the ‘wedge’ from the top bar, assemble the top bar, sidebars and bottom bars. Use a nail gun or frame nails (gimp pins) depending how much you value your thumb and fingers.

I always use wood glue on the joints, with the sole exception of the bottom bar on the face of the frame that the wedge was removed from if I’m going to add a sheet of foundation. That bottom bar is usually added after the foundation is fitted.

For a foundationless frame both bottom bars can be glued for additional rigidity and longevity (however, see also the section on ‘recycling’ below … I often convert frames previously used with foundation into foundationless frames).

Once the frame is ready I glue in wooden tongue depressors to provide the starter strip from which the bees will start drawing comb. These are the guides that keep the comb straight (or at least ensure it starts straight). See the additional comments on starter strips below.

I then nail the wedge back in place in exactly the same way as I would if I was using foundation.

If you’re building new foundationless frames it’s easier to drill the top bars or sidebars for the supports (see below) before assembling the frame. However, if you’re reusing frames, it’s easy enough to do this ‘as and when’.

Comb built on a frame as described will have little or no lateral support and will need delicate handling. To make things more robust you need to provide some sort of support that is incorporated into the comb as it is drawn.

I’ve used three different types of support for the comb in my foundationless frames – nylon monofilament, bamboo skewers and stainless steel wire.

Nylon monofilament

All my early foundationless frames were built with 40 – 50 lb breaking strain nylon monofilament (‘mono’). You can buy bulk spools of this for sea fishing. Buy the cheapest stuff you can find but don’t be tempted to use lower breaking strains as the bees can nibble through it.

Mono is reasonably easy to handle. You need to drill holes in the sidebars and thread the mono through, starting with a loop over a drawing pin. After pulling it tight, wrap it around another drawing pin and drive it home.

Foundationless frame with monofilament

If the mono cuts into the sidebars, add a staple to take the strain (see discussion of stainless steel wire below).

I’ve got lots of these frames still in use. However, the mono stretches in the steam wax extractor and it needs to be replaced before the frame can be reused. For this reason I’m slowly replacing these frames with one or other of the alternative supports below.

Bamboo

These are the easiest foundationless frames to build. Two small holes in the top bar, push a 3 mm bamboo BBQ skewer up, point first, jammed into the hole. Glue in place, top and bottom, and cut off the excess after the glue has set.

I’ve used hundreds of these frames and they’ve been excellent. The bees tend to build the comb in three separate ‘panels’ to start with, only joining them laterally with the second or third round of brood rearing. They’ll often build entire panels of worker or drone brood. If it’s not what you want it’s simplicity itself to cut out with the blade of a hive tool.

Foundationless triptych …

Two skewers is sufficient in a standard brood frame. I’d be wary about using bamboo skewers on 14 x 12’s just because of the extra weight of the deeper comb before the panels are joined together.

Stainless steel wire

More recently I’m building my foundationless frames with stainless steel wire. This is less pleasant to handle – I use one Michael Jackson-esque work glove for protection – but is incorporated well into the drawn comb.

Foundationless frame with vertical stainless steel wiring

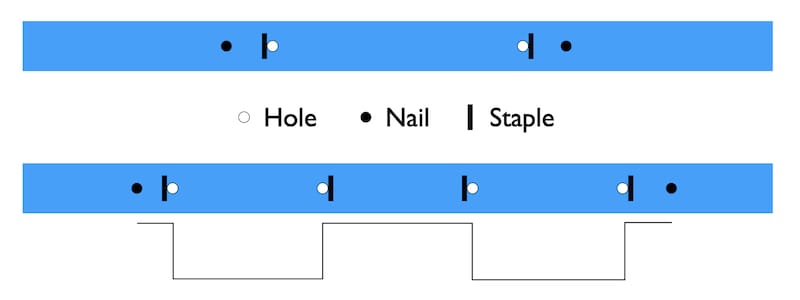

Drill 2 or 4 small holes in the top bar, adding a stainless steel T50-type staple on the appropriate side of the hole to prevent the wire digging into the wood. Drive two frame nails part-way in 1 cm or so away from the outer holes.

Template for the top bars of wired foundationless frames

Add T50 staples perpendicular to the bottom bars, using the same spacing.

Cut off sufficient stainless steel frame wire, with about 6 cm excess, and wind 3-4 turns around one of the frame nails before driving the nail in flush with the top bar {{4}}. Important now stretch the wire taught before threading through the frame. This helps prevent the wire kinking when you thread the frame. Wear a glove for this and for tightening the wire.

T50 staple through the bottom bars

Thread the frame, carefully pull the wire as taught as you reasonably can, wind the end of the wire around the second frame pin and drive the latter home. The two tail ends of the wire can be easily twisted off and the frame is finished.

Top bar detail

With imagination you can experiment with other wiring patterns; three holes in the top bar and two staples in the bottom bars generates an aesthetically-pleasing {{5}} W pattern, for example.

If you use 14 x 12’s then you probably need four evenly-spaced wires. Leo Sharashkin does this on the large frames in his Layens hives.

Supers

I have dozens of foundationless super frames, all built with horizontal mono support. These have been in use for almost a decade and go through the radial extractor once or twice a season with very few breakages.

Super frames …

I’ve never used vertically wired super frames, or super frames with bamboo supports. I might try the former out of interest {{6}}, but wouldn’t attempt the latter. The thicker bamboo takes more time to be incorporated into the comb, and I would be concerned that the frames would always be a little too weak for the rough and tumble of the extractor.

Starter strips

Don’t be tempted to use strips of commercial foundation for starter strips and don’t bother daubing the wooden tongue depressors with melted wax to ‘help’ the bees.

Why do I say this?

I built a dozen frames with three different types of starter strip positioned randomly; wood, waxed wood and foundation. I used these for a season and observed which the bees ‘preferred’, as determined by which they chose to use first.

Take your pick …

The bees showed no preference whatsoever, so I only ever now use plain wooden starter strips as they are easier to prepare and a lot more robust.

Frame making is a bit of a chore, so any shortcuts are very welcome 😉 .

Using foundationless frames

With one or two caveats you use foundationless frames in exactly the same way you would use a frame with standard wax foundation, or even plastic foundation.

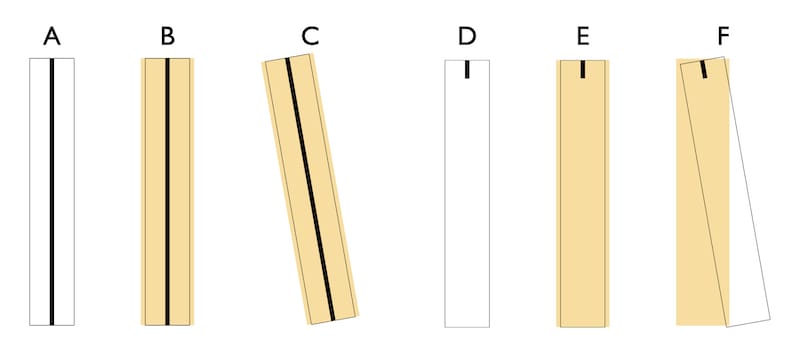

I don’t know much about the mechanics of comb building. Comb is drawn vertically (almost always down, but they can build up into a void) and built out to the required cell depth from a central midrib (A and B, below).

Comb is drawn vertically

A sheet of foundation provides this midrib and is dominant over the tendency to draw comb vertically. This means that your frames will – within reason – still be drawn properly if they do not hang vertically (C above).

In contrast, a foundationless frame by definition lacks the central midrib until the bees build it, and they build it vertically. Consequently, there is a danger that the comb in a foundationless frame will not be in the same plane as the sidebars (D to F above) unless the frame is vertical.

Believe me … this way lies madness. The frames cannot be reversed, and they do not fit into other hives.

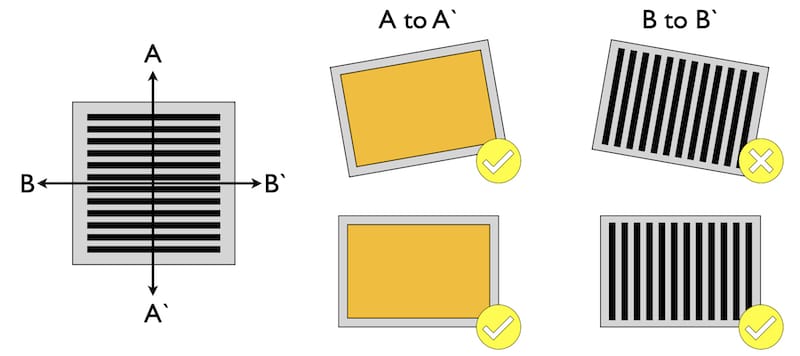

The solution is simple. The hive must be perfectly level when viewed along the plane of the frames (B to B’ in the diagram below). In the other orientation (perpendicular to the face of the comb, A to A’ below) the hive does not need to be level.

Levelling hives for foundationless frames

Most smartphones have a spirit-level app that will help if needed.

Mind the gap

If you present a colony of bees with an empty void they will fill it with beautiful natural comb. Some of it might be in nice parallel sheets, but often they adopt all kind of weird and wonderful shapes.

Although the starter strips are included to encourage the bees to draw parallel comb they sometimes fail to take the hint. I get the impression this is a particular problem during a really strong nectar flow or when being fed copious amounts of syrup.

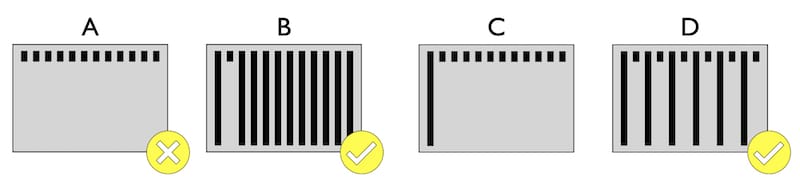

To avoid this from becoming an issue avoid presenting the bees with a complete box of foundationless frames (A, below). Instead, introduce frames one or two at a time, flanked with frames with foundation or drawn comb (B).

Getting comb drawn nicely with foundationless frames

You should always use foundationless frames in bait hives (to give the impression of a suitably-sized void e.g. C, above), but add alternating drawn comb or foundation soon after the swarm arrives (D).

Likewise, if I was using foundationless frames for a Bailey comb change, I would alternate them with frames containing foundation (D) {{7}} .

Drones

In natural comb the bees will build ~17% drone comb. This ‘investment’ reflects the importance of drones in passing on the genes during swarming and queen mating. In contrast, if you only provide worker foundation in your frames you are likely to be used to a significantly lower level of drone comb, and consequently drones, in your hives.

One of the surprises when switching to foundationless frames is the amount of drone comb the bees will draw.

Don’t worry … they’re only trying to achieve that 17% figure (which is almost two full frames in a brood box).

Beautiful newly drawn comb …

I’m proud of my drones and I want them to get out and donate their good genes (and die trying!) to the local honey bee population, so these additional drones don’t worry me at all.

However, they could cause a problem if your mite control is poor. Varroa preferentially reproduces in drone brood and generates more progeny. If your mite levels are high at the start of the season they may rapidly get out of control and necessitate some sort of midseason intervention.

The solution to this is to take a lot of care to minimise mite levels in the winter, when the colony is broodless. That means the colony starts the season with very low levels and – irrespective of the level of drone brood available – they should never reach dangerous levels.

Don’t ignore the benefits of foundationless frames from fear of mites … control the mites properly and all will be well (whether you use foundationless frames or not).

Reusing foundationless frames

A well built frame can be cycled through the steam wax extractor several times and still remain rigid and reusable. I’ve got frames that have probably gone through four or more times during their ‘lives’, so reducing frame costs from a nominal 77 p each to less than 20 p.

One of the advantages of foundationless frames is that the supporting wires (or bamboo) remain attached to the frame, rather than being melted out with the comb. That means the frames can be cleaned up more quickly, scrubbed down with soda, dried and then reused. If you use wire or bamboo supports they might need no additional preparation.

Steam wax extractor and foundationless frame

As I periodically recycle my frames that contained foundation I often convert them to foundationless. Prize out the wedge, scrub the frame clean, allow to dry and then add the wooden starter strips. Drill the top bar, wire the frame and hey presto you’ve one less frame to make for the season ahead 🙂 .

Miticide residues and commercial foundation

I’m not saving the best to last, but here is is another compelling reason to use foundationless frames (at least some of the time).

Any commercial foundation you purchase – perhaps with the exception of the very expensive organic stuff {{8}} – will almost certainly be contaminated with wax-soluble miticide residues.

I’ve qualified this with an ‘almost’ as not all foundation has been tested. However, there is an international trade in recycled beeswax and the foundation I am aware of being tested – in the USA – is contaminated. Here’s a relevant quote from the abstract of Mullin et al., (2010):

Almost all comb and foundation wax samples (98%) were contaminated with … fluvalinate and coumaphos, and lower amounts of amitraz degradates and chlorothalonil, with an average of 6 pesticide detections per sample and a high of 39.

Fluvalinate and coumaphos are synthetic pyrethroids, the former being the active ingredient in Apistan strips. Amitraz is the active ingredient in Apivar strips and chlorothalonil is a fungicide.

Miticide residues contaminated with beeswax

Where do these contaminants come from? The clue is in the phrase ‘recycled beeswax’ … the miticide residues come from prior treatment of hives to control Varroa. The chlorothalonil probably originates from exposure of bees when foraging.

Detrimental effects of miticides on bees

There is contradictory evidence about whether these traces of miticides are damaging. Exposure of individual bees, particularly queens and drones, is probably detrimental (though it is arguable whether all these studies used field-realistic miticide levels), for example:

- Sublethal doses of miticides can delay larval development and adult emergence, and reduce longevity (Wu et al., 2011)

- tau-fluvalinate- or coumaphos-exposed queens are smaller and have shorter lifespans (Haarmann et al., 2002)

- Queens reared in wax-coated cups contaminated with tau-fluvalinate, coumaphos or amitraz attracted smaller worker retinues and had lower egg-laying rates (Walsh et al., 2020)

- Drones exposed to tau-fluvalinate, coumaphos or amitraz during development had reduced sperm viability (Fisher II & Rangel, 2018)

Despite this, a recent study has shown little or no effect of miticide contamination on either colony expansion or overwinter survival (Payne et al., 2019).

Miticide resistance

However, these are miticides. They may or may not be detrimental to bees, but they are detrimental to mites.

However, at the low levels contaminating foundation they probably aren’t detrimental enough. Instead, they could well contribute to the selection of miticide-resistant Varroa.

I’m not sure if there is scientific evidence from Varroa supporting this (but I’d bet my mortgage there would be if someone bothered to look), but exposure to sub-lethal levels of a compound is a classic strategy to select for – and maintain – resistance in a population of parasites or pathogens. It’s why you’re always told to finish the course of antibiotic treatment, or not use just one Apivar strip in a brood box.

I don’t use Apistan as mite resistance is so widespread. However, tau-fluvalinate residues are undoubtedly present in all my colonies from commercial foundation. That these residues may contribute to continuing Apistan-resistance in the mite population seems somewhat ironic.

I therefore reduce my use of commercial foundation and use 40-60% foundationless frames.

Conclusions … I know it makes sense 😉

Beekeeping is one of those wonderful hobbies that you can have a lot of enjoyment from and (more than) cover your outgoings from honey sales. By reducing your outgoings you can increase your income or – to think of it in other ways – you can give away more honey to friends and family, or pay for all your miticides and winter feed, without cutting into the ‘profit’.

And have fun.

Of course, most of us don’t keep bees for profit, and would keep them even if we didn’t sell the honey.

Nevertheless, by reducing the cost of replacement frames and foundation – the bulk of which is foundation if you reuse your frames – then it reduces the overall outlay associated with keeping bees.

But the arguments for using foundationless frames (some or all of the time) are not just economic.

New comb with queen already laying it up

The bees appear to do very well on foundationless frames. Comb is drawn fast and, once the mono, wire or bamboo supports are incorporated, is as robust as comb built on foundation. There are more drones in the hive which – assuming your bees are well-tempered – I consider a good thing. And – as if that lot wasn’t enough – trace levels of miticides are reduced.

Finally, frames without foundation are easy to store. There’s no foundation to go brittle in the cold, or that develops a waxy white bloom which slows the bees from drawing comb. At the height of the season you’re not dependent on the supplier having foundation in stock as your frames are always ‘ready to go’.

Give them a try and tell me how you get on.

References

Fisher II, A., and Rangel, J. (2018) Exposure to pesticides during development negatively affects honey bee (Apis mellifera) drone sperm viability. PLOS ONE 13: e0208630 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0208630.

Haarmann, T., Spivak, M., Weaver, D., Weaver, B., and Glenn, T. (2002) Effects of Fluvalinate and Coumaphos on Queen Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Two Commercial Queen Rearing Operations. Journal of Economic Entomology 95: 28–35 https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-95.1.28.

Mullin, C.A., Frazier, M., Frazier, J.L., Ashcraft, S., Simonds, R., vanEngelsdorp, D., and Pettis, J.S. (2010) High Levels of Miticides and Agrochemicals in North American Apiaries: Implications for Honey Bee Health. PLOS ONE 5: e9754 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0009754.

Payne, A.N., Walsh, E.M., and Rangel, J. (2019) Initial Exposure of Wax Foundation to Agrochemicals Causes Negligible Effects on the Growth and Winter Survival of Incipient Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Colonies. Insects 10: 19 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6359559/.

Walsh, E.M., Sweet, S., Knap, A., Ing, N., and Rangel, J. (2020) Queen honey bee (Apis mellifera) pheromone and reproductive behavior are affected by pesticide exposure during development. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 74: 33 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-020-2810-9.

Wu, J.Y., Anelli, C.M., and Sheppard, W.S. (2011) Sub-Lethal Effects of Pesticide Residues in Brood Comb on Worker Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Development and Longevity. PLoS ONE 6: e14720 https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014720.

{{1}}: There’s a difference between cutting edge and last minute, but it’s subtle.

{{2}}: BKA’s may well get discounts, and you’d be advised to take advantage of them if you have the opportunity.

{{3}}: Throughout this I’m quoting DN5 or SN5 National frames, not 14×12’s.

{{4}}: The point may protrude through a millimetre or two … ignore it.

{{5}}: Though possibly no better.

{{6}}: In particular for heather cut comb.

{{7}}: D’oh! It’s late and I’ve just realised the last two diagrams show 12 frames in a box … let’s hope no one else spots this. It can be our secret.

{{8}}: Can you even still buy this??

Join the discussion ...