Good times ahead

Synopsis : The season is approaching, but it’s not here yet. Don’t be misled by social media. Do your preparations for the good times ahead and the reinforcements, revisions, reversals and revelations.

Introduction

Social media can be a bit of a curse for beekeepers – in particular new beekeepers – as we falteringly transition from winter to spring. Twitter is littered with pictures of bees foraging busily, lots of opened boxes and comments on the numbers of frames of brood. Some colonies are being united and supers are going on.

STOP!

Unless you live in mid-Spain, you’re not missing out. Don’t even think of doing any of that nonsense.

These pictures are often posted by very experienced beekeepers running many, many hundreds of colonies. They know exactly what they’re doing. They have to start early to have colonies ready for top fruit pollination contracts, or boosted and bulging to properly exploit the oil seed rape. They’ve done this for years; they’re fast, efficient and have completed a risk/benefit analysis of financial gain vs. potential colony harm.

A frame from May … not February

This is the way experienced professionals manage livestock. It’s a world away from amateur beekeeping.

Alternatively, they’re posted by click-craving numpties bragging in a ”mine’s bigger than yours” manner, potentially leading hundreds of beginners into thinking that they should also be doing something, anything, with their bees.

Or, perhaps they’re in New Zealand?

Don’t worry … the season has not yet started. At least not in the UK it hasn’t.

Even when I lived in the semi-tropical Midlands (Ahem!) I don’t think I ever inspected a hive in February, and rarely did until the second half of March.

And, now I live in Scotland, it’s sometimes a month or more later than that.

Inspected vs. opened.

There’s a difference between inspecting a hive and opening a hive. ‘Inspecting’ involves disruption of the bees, removal of the frames etc. You’re looking for something, and if you’re not then you probably shouldn’t be disturbing the colony.

I can’t think of anything amateur beekeepers should be looking for in their hives during mid-February.

I have looked in the brood box to confirm whether a colony is broodless prior to oxalic acid treatment in midwinter (or, more accurately, mid-November as they’re usually rearing brood by the turn of the year). However, whilst this undoubtedly does disrupt the colony, I’m quick, efficient and I’ve done the risk/benefit analysis 😉 .

This isn’t really an inspection. I don’t look at every frame. Instead I use my years of experience and exceptional judgement ‘eyeball’ where the centre of the cluster is, split the frames there and look at the opposing faces. If there is any brood it’s not going to be at the periphery.

But I much prefer not to do that and usually use a combination of ’reading the runes’ on the Varroa tray and my notes from previous years.

Tray removed in mid-February showing lots of evidence of brood rearing in this colony

However, sometimes it is necessary to open a hive in the winter, for example to top up the stores if the hive feels light, or to apply a pollen pattie to boost brood rearing.

And brood rearing is now starting to ramp up. I’ve been weighing some colonies and they’ve lost more weight in about the last month than they did in the previous three. If your hives feel light then they probably are light.

Don’t delay, or be stingy, or make the bees move far, or use clingfilm

The next month or so is the time with the maximum risk of the colony starving. They’re rearing brood, but there’s little forage available. If they run low on stores – at best – they will stop rearing brood.

At worst they’ll perish 🙁 .

Don’t delay, don’t wait for one of those fleetingly rare ‘good flying days’ this early in the season before adding some fondant. It takes just a few seconds and you can have the roof and crownboard off and back on again almost before they know it.

Avoid a howling gale, or torrential rain, but otherwise get on with it.

I know some beekeepers add fondant in 100-200 g blocks, wrapped in clingfilm, above the hole in the crownboard.

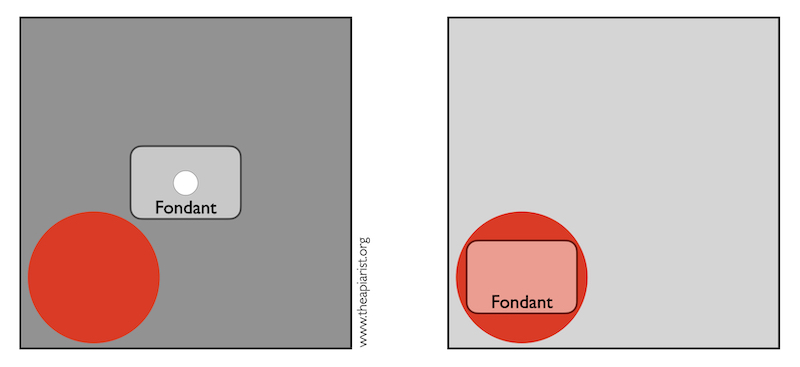

Which bees are better able to access the fondant? Over the crownboard (left) or over the cluster (right)

I think there are better ways to add it:

- prepare 1-2 kg blocks of fondant in those translucent containers ‘shrooms or chicken are packaged in at the supermarket. Waste not, want not.

- add the block directly over the cluster, under the crownboard. Either use an eke or a reversible insulated crownboard. This means the bees don’t have to access a cold void to get to the fondant.

- cover the face of the fondant with thick polythene with a 5-7 cm opening cut in it for the bees to gain access. If you use clingfilm they pull it down between the frames and integrate it into wax. Very messy.

Why a kilogram or two? Because they’ll use it. They need to rear a lot of brood for the spring nectar flows. One hundred grams won’t last long at all. I don’t want to be repeating this every few days …

Remove the clingfilm before placing them over the cluster under the crownboard

But some hives won’t need any top-ups. My Fife colonies often finish the winter with a frame of unused stores.

I steal these for making up nucs.

Spring might not have sprung, but it will

I spent the afternoon working outdoors until well past 5 pm when the light started to fail (remember, I’m at 56° N). Clearly the days are getting longer.

Despite two protracted cold spells this winter – sub-zero temperatures and lying snow for a week, unusual this far north and west – the first measurable signs of spring suggest it might be a relatively early one.

We don’t have any snowdrops or crocus. The garden is just rough hillside scoured by rapacious deer. If there were any snowdrops or crocus they would have been eaten long ago.

But the frogs are already mating.

Frogspawn – early March 2020

There’s frogspawn in the pond, a good 2-3 weeks earlier than many years.

I’ve talked about phenology before. This is the observation of cyclic and seasonal natural phenomena. Since I last mentioned it I’ve discovered the Woodland Trust’s excellent Nature’s Calendar website. This allows you to record seasonal events, like the first frogspawn, or arrival of cuckoos, or the flowering of certain plants.

Perhaps more useful and interesting, you can see recordings made by others across the country over this and past years. And, with a little animated GIF trickery, you can observe the wave of activity progressing up the country.

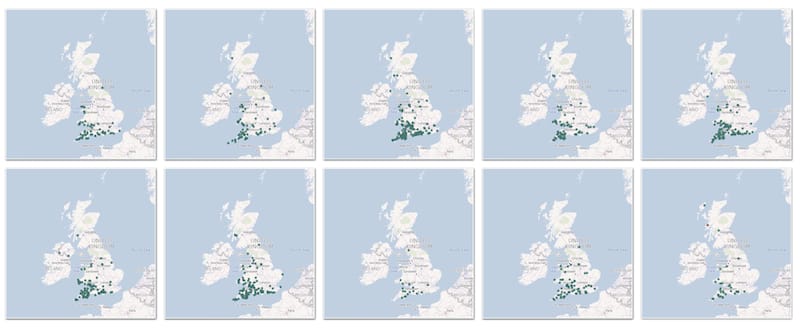

First frogspawn 2022

The image above is the first frogspawn last year, for 3 months from the 9th of January. The first records for Scotland were the 18th of February. This year they’re a week earlier, and much further north.

If it’s raining, or too soon to check the bees (it is!) you can have hours of fun querying the historical records. Compare the arrival of cuckoos and the appearance of frogspawn … two very different patterns.

Interesting but not perfect

Unfortunately for beekeepers only a few things directly relevant to our bees are recorded in the Nature’s Calendar – the first flowering of hawthorn, blackthorn and snowdrops.

We really need something that includes the key nectar-yielding trees like willow, sycamore and lime, and other native forage like blackberry, dandelion and clover. Willow might be problematic, there are so many hybrids they tend to flower at all sorts of different times. In the same way, the strain-specificity of agricultural crops is probably too variable to be useful.

If you knew that a particular nectar source had just started flowering 100 miles south you could pile the supers on and smugly sit back knowing you’d not missed the start of the flow.

Maybe such a thing exists … does anyone know?

In the meantime, the best I can do is keep an eye on other cyclic and seasonal events and refer to my never-quite-comprehensive-enough hive and apiary notes to work out when spring will really be here.

And when it does, the fun will begin

I’ve been keeping bees long enough to have a fair idea about what I’m doing, but nothing like long enough to get anywhere near it feeling repetitious, or dull or even unchallenging.

Well OK … the novelty can quite quickly wear off on a swelteringly hot afternoon, with bloated, heavy supers and lots of hives to inspect. Likewise, filling mini-nucs in the rain for the season’s first round of queen mating (it’s always in the rain 🙁 ) isn’t the most enjoyable task.

And, come to think of it, nor is taking the summer honey off in a ‘bad wasp’ year {{1}}.

Hot day, hard work …

But, looking back, I struggle to remember those things.

Beekeeping has been good to me, and like any pastime you keep doing, you remember the good times. And there have been many of them.

At this time of the year, on the cusp of the new season, it’s the anticipation of more of those good times, more problems solved, tricks learnt, and connections made, that make the wait frustrating (but nevertheless necessary).

I wrote something on how to start beekeeping a couple of weeks ago. I tried to be rational and pragmatic, and included sentences like:

Expect disappointing weather, temperamental bees and possibly even lost swarms, several head-scratching ”WTF? I don’t understand … 🙁 “ moments, worry and – perhaps – some honey.

The intention was to ‘manage expectations’.

Beekeeping is not always easy. Sometimes it’s not easy at all.

However, perhaps I overdid things? Fred made a very relevant comment which included the words “[don’t] forget to enjoy and cherish those starting steps”. He’s right. Some of my best memories are from my early years of beekeeping.

But there are good things every year.

The four R’s

One of the great things about keeping bees are the subtle variations – from colony to colony, from apiary to apiary, from month to month, and from season to season. It’s never quite the same.

Similar perhaps, but never identical.

All of which means that understanding what’s happening in the colony, and knowing what to do and when to do it, requires you learn how to interpret which of these subtle differences is important … and which is just noise in the system.

Sometimes this is easy; colony defensiveness is significantly influenced by the environment (weather and a reduction in nectar flow) and how the colony is handled. If your bees are defensive you need to either exclude these as factors and worry about lousy genetics, poor quality drones and promiscuous queens, or – thankfully – explain it away in terms of a plummeting barometer or the OSR going over.

Going over …

So the observant beekeeper is constantly learning, deciphering the signal from the noise, working out what matters and what doesn’t.

And because each season is ’the same, but different’ each new season the things learnt – or at least noted – in previous years are revisited.

In my mind these things are one of the four R’s; reinforced, revised, reversed or revealed.

Reinforced

Some things just work {{2}}. Like many beekeepers I have dabbled with a range of methods for many routine colony manipulations – swarm control, requeening, uniting or whatever.

Over time you end up using one method in preference to the others. Because you use it more, you get better at understanding the quirks and ’gotchas’, and the method gets ‘better’. You can measure ‘better’ in a variety of different recognisable ways, or any way you want – faster, more likely to work, cheaper, less lifting, more productive or environmentally friendly – depending upon what you are trying to achieve (possibly vs. the cost of it failing altogether).

The reinforcement is of course partly self-fulfilling – the more you do something the better you should get at it – but it is also a feedback process. Because it works well, or as you want, or as expected, you are likely to repeat the method next time you need it.

Uniting colonies over newspaper

If I need to apply swarm control I’ll almost always use the nucleus method, if I’m uniting colonies I’ll use newspaper with the moved brood box on top, and I always add a new queen in a sealed cage, without attendants, and only plug it with fondant when the recipient colony stops showing aggression.

And the season we’re about to start on will undoubtedly involve more of this reinforcement. Some might interpret this as me getting old(er) and stuck in my ways, but I like to think of it as not changing a winning formula 😉 .

Revised

The quirks and ’gotchas’ I referred to above might be trivial, or they could fundamentally alter the success or feasibility of a method. It’s very unlikely that the approach I now use is exactly the same as the one I used when I first tried something … not least because I usually get it wrong a couple of times before I get it right.

All of which means that there’s a gradual evolution of some methods from season to season. Little tweaks here and there that improve things become a permanent fixture in future years. Modifications that make little or no difference, or (Oh no!) make things worse are quietly forgotten abandoned.

Actually, don’t quietly forget them or you’re likely to repeat them in the future. Make a careful note, even if it’s just a mental one.

This is ”Do as I say, don’t do as I do” advice 😉 .

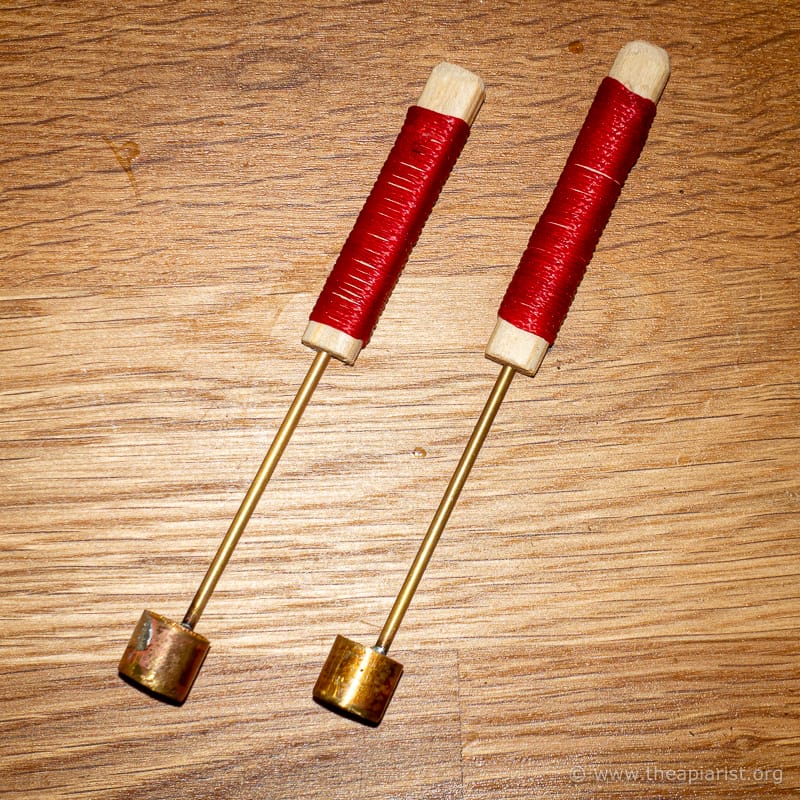

Cell punches

I’m trying some non-grafting queen rearing methods this season. I tried some last season as well, with variable levels of success.

In this instance, variable means nothing like as good as I’d like {{3}}.

It’s too soon to give up on them, but it felt as though I was a long way from them being dependably workable. I’ll revise what I tried and try again.

Reversed

But, if after a couple more goes, I still feel I’m struggling then I’ll abandon an approach and put it down as an unsuccessful, but valuable, learning experience.

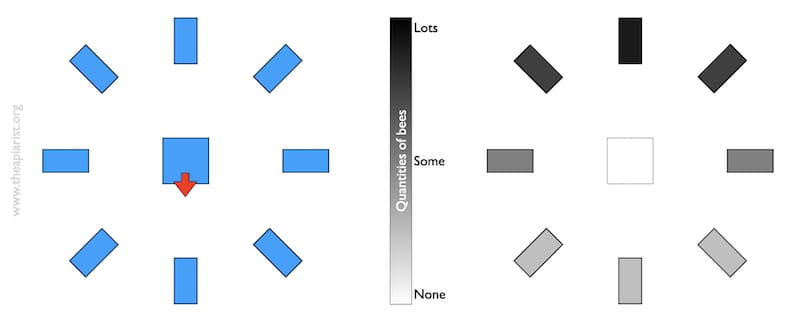

Circle splits are a good example. This is a method of making up multiple nucs, each getting a mature queen cell for mating.

Here’s one I did earlier …

The principle is straightforward. You split a strong {{4}} colony 4, 6 or 8 ways, putting two frames of brood and the adhering bees into nuc boxes arranged in a circle around the colony being divided. The nucs are arranged equidistantly from the centre of the circle and even distributed around it. The hive containing the original colony – now empty – is removed and the queen cells are added.

Since the original hive has now gone, the returning foragers are supposed to distribute themselves evenly to the surrounding nucs.

The method is described in Vince Cook’s book Queen rearing simplified. It makes sense in principle … but in practice I’ve usually struggled.

How it started (left), how it ends (right)

Some nucs get over-populated while others get depleted of bees.

There seem to be two reasons for this; the first is that nucs that face broadly the same way as the original hive attract more bees than the others. The second appears to be due to the desirability of the new queens; whether this is due to pheromone strength, or the order in which they get mated, I’m not sure. The result is potentially yet more inequality in the worker population.

If you’re lucky the two counteract each other and all is well.

But I’d prefer not to rely on luck.

You also need a lot of level(ish) space around your hives – a luxury I rarely have.

Unsurprisingly I’ve stopped using this method.

Revealed

The reinforcement, revision and reversal are all about stuff I already know.

But the great thing about beekeeping is that the coming season will also teach me {{5}} new stuff I didn’t know.

And, if I’m lucky, several new things.

On the west coast I’m hoping it’s about increasing my heather honey crop as it was pretty woeful last year. I think I was the victim of poorly sited hives, poorly prepared colonies and lashings of rain.

I can’t do much about the last of these, but I may have a solution to the first and will do my best with the colony prep.

In contrast, I had a stellar season on the east coast. I can’t imagine things going much better.

Of course, I’ve no idea what new things I’ll learn. Sometimes they’ll appear in one of those ‘lightbulb moments’, but often they barely register and it won’t be until days or weeks later that I’ll realise “Ah ha!”.

But one thing I learnt years ago is that you can easily start beekeeping too soon in the year. There’s nothing to be gained from rummaging around in the boxes before you’ve got reliable foraging weather and the colonies have had a chance to build up after the winter.

You risk being disappointed by colonies that look weaker than you’d hoped and more bad tempered than you’d like. Or, more importantly, you might chill the brood and hold the colony back.

Build some more frames, re-tidy the bee bag, check the smoker, re-read your notes (or prepare to take better ones), plan stuff and it won’t be long until you can hang out the sign:

Amphibian notes

Did you know that tawny owls eat frogs? I watched a tawny owl 20 yards from my back door ‘still hunting’ (essentially perching in one spot scanning the ground below) in a larch overlooking the pond which is hoachin’ with frogs.

I made the animated image of the first frogspawn very late one night and had to cut some corners due to time and file size constraints. Here are snapshots of the 14th of February over a decade, from 2014 (top left) to 2023 (bottom right).

St. Valentine’s Day frogspawn 2014 to 2023

{{1}}: Frankly, that can be bloody awful.

{{2}}: Like my 6 year old Mac laptop, which recently replaced my 12 year old one.

{{3}}: Yes, cell punching, I’m talking about you.

{{4}}: De-queened, obviously!

{{5}}: Reveal … a contrived alliteration I hope you’ll forgive.

Join the discussion ...