Poly nucs and winter losses

Synopsis : Save money. Take your winter losses now. Unite weak colonies or those headed by dodgy queens … and some thoughts on poly nucs for overwintering.

Introduction

With apologies to Winston Churchill:

“Now this is not the end. It is perhaps the beginning of the end.” {{1}}

And even a cursory look through couple of colonies will confirm this. They are shifting from their summer labours to the late summer preparations for winter.

The signs are easy to spot.

Colonies with ample super space are beginning to backfill the broodnest with nectar. You can see it sparkling in the sun.

Backfilled cells (and a drone or two)

You also see this when the colonies have nowhere else to store fresh nectar, but my supers are disappointingly full of space this year {{2}} ) so they’re opting to keep it close. The brood pattern can look a bit spotty, but the queen is ‘missing’ the cells because they’re already full.

Most of my east coast colonies have stopped, or almost stopped, rearing drones. There are still plenty of drones about but they’re not producing any more this season.

This makes sense. Drones are ‘expensive’ in terms of the resources (pollen, nectar, time, workers) needed to rear them and the chance that they will successfully complete a mating flight this late in the season is limited.

They’re not chucking them out yet though. On a warm afternoon the distinctive sound of a thousand drones going out ‘on the pull’ fills the air.

Ever the optimists 😉 .

Colonies are still strong and busy. They contain a lot of brood, but the laying rate of the queen is slowing and – presumably {{3}} – they will very soon start rearing the long-lived winter bees that will take the colony through to next spring.

Take your winter losses now

And, as the colonies segue from producing summer bees to winter bees, I’m also starting to plan for the winter. This involves preparing the colonies I want and getting rid of (i.e. uniting) those surplus to requirements or underperforming.

It’s better to make these decisions before feeding and treating for mites. If you don’t there are two (or perhaps three) inevitable consequences:

- You’ll have the unnecessary expense of feeding and treating colonies that you subsequently decide to unite. I reckon this costs me about £16-17 per colony, assuming fondant prices haven’t gone through the roof {{4}}.

- If you subsequently decide to unite two colonies you’ve already fed and treated you’ll be doing it in mid/late October, which is far from ideal … so you’ll probably not bother and aim to deal with the colony next year, in which case …

- Some of the colonies you should have united in mid/late August will die overwinter – poor queens, understrength etc. – meaning you not only have the financial loss of the food and miticides, but you also have no colony at the beginning of the next season.

So … take your winter losses now 😉 .

Late season inspections

It’s actually somewhere between mid-season and late-season, but erring towards the latter.

My last full colony inspection, by which I mean every frame in the brood box (and sometimes every frame shaken free of bees to check the brood very carefully) was several weeks ago.

Queenless colony … she was in my marking cage, the last queen of the season

By early/mid August my inspections are much more selective:

- Colonies with this year’s queens may have already had their last inspection. If not I’ll have a peek when I take the honey off and feed/treat. If the behaviour is good and the colony is strong there’s no chance I’ll not be overwintering them. Since the queen pheromone levels will be high there’s also little to no chance of swarming, so there’s no point in rummaging unnecessarily through the brood box. Leave them to get on with things 🙂 .

- Understrength colonies or those with a questionable temperament get looked at more carefully. Are they understrength simply because the queen took her time getting mated, or because I harvested frames of brood to make up nucs? In these cases they will make up the shortfall and should be fine if the queen is laying well. However, if they’re understrength because the queen is failing (lots of missed cells, drone brood peppered about, unseasonably low laying rate) then they will be united (having removed the queen). Similarly, a colony that repeatedly behaves badly will probably have the same fate … why should I put up with surly bees? {{5}}

- For the same reasons (i.e. potential queen failure) colonies with aging queens get looked at carefully.

- Nucs destined for overwintering are also carefully checked as they must be strong to successfully overwinter them.

Winter losses

Annual colony losses are reported to vary between about 10% and 40% based upon national association surveys. As I’ve previously said, I don’t really trust any of these figures as I don’t think they are validated with any rigour.

I’m sure most survey respondents are predominantly truthful, but I suspect some beekeepers who experience particularly high losses never respond (some abandon beekeeping). This will result in overall losses being underestimated.

The figures from one survey last year were particularly strange. 84% of beekeepers reported no losses at all. Overall losses were reported to be 16% (only 1% in Wales!) and, of those, only 12% were due to Varroa or DWV. However, 33% of beekeepers also reported that they used no miticides.

Really?

It would be good to see some validation of these numbers.

All of which is a bit of a digression. Individual beekeepers should aim to minimise their winter losses by ensuring the colonies that they take into the winter have the best chance of surviving. Personally I think responsible beekeepers should try and avoid unnecessary colony deaths.

In addition, I really dislike dealing with messy, mouldy frames from a ‘dead out’ on a raw March morning.

Just back to those reported losses for a second … 38% were thought to be due to ‘queen problems’ e.g. the death of the queen, drone laying queens or ageing queens {{6}}. Whilst I’m surprised that these were more than three times more frequent than the Varroa/DWV double-whammy, queen failures are a significant cause of winter colony failures and so it makes sense to try and avoid them before they happen.

Other than taking off the honey, my colony inspections and manipulations in August are all associated with minimising my winter losses.

Nucs

Overwintered nucs are really useful.

With a well-mated young queen they’ll take off like a rocket in the spring, often building up fast enough to get a crop of spring honey. Alternatively, if you do lose colonies overwinter, perhaps because you failed to apply some tough love in the autumn, then an overwintered nuc can be used to repopulate the hive, so restoring colony numbers.

Here’s one I prepared earlier … an overcrowded overwintered nuc in April

Or you can sell them to the first flush of eager new beekeepers who have completed their ‘Begin beekeeping’ courses in draughty church halls {{7}} during the interminable dark winter evenings.

Overwintered nucs, with a proven queen, are rightly valued more highly than a nuc in mid-June.

And the great things about nucs is that they’re relatively easy to overwinter with the right preparation. I think this involves three things:

- ensuring they are as strong and healthy as possible going into the winter, with a young, well-mated queen.

- feeding them properly and then usually topping them up with fondant as needed through the winter. You cannot have a lot of bees and a lot of stores in a 5 frame nuc box.

- helping them minimise the stores they need to use by housing them in a well-insulated nuc box.

I’ve overwintered nucs in cedar boxes in the past, but the availability of high quality, well-insulated, polystyrene nuc boxes has made things a whole lot easier.

All poly nucs are equal, but some are more equal than others

The quality of the insulation provided by a poly nuc depends upon two things {{8}}, the:

- thickness of the walls and roof

- thermal insulation of the material (which is probably correctly expressed as the K-, R- or U-value for thermal conductivity, resistance or transmittance)

I don’t have values for the latter and I’m not aware that they are published … so let’s assume that all poly nucs are made from the same stuff (I’ll return to this briefly later).

I’ve bought at least five types of poly nuc over the years. Like many I started with Paynes (which was one of the first available). I’ve got a few Paradise boxes {{9}}, two varieties from Maisemore’s and the majority are Thorne’s Everynucs. I’ve not used the Paradise boxes for years so I’ll ignore those.

I measured the walls and roof of all but the Paynes boxes (which are in storage). Everynucs are thick walled and have a pretty substantial roof. There are two Maisemore’s designs; one with an integral floor and recessed handholds in the end walls, and another with a separate floor and plain-sided brood box.

| Make | Roof thickness (mm) | Wall thickness – side, end (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Thorne’s Everynuc | 35 | 40, 40 |

| Maismore’s – integral floor | 20 | 30, 25 |

| Maismore’s – separate floor | 40 | 30, 60 |

| Paynes | Thin | 20? |

Despite the two Maisemore’s boxes being the same outer dimensions, and with some interchangeable parts, the poly thickness of the end wall (because of the handholds) and the roof are less in the version with the integral floor.

Two Maismore’s roofs

If I was buying more – and I did this year – I’d get the version without the integral floor. Better insulated and altogether more flexible.

K-, R- or U-values?

‘Better insulated’ assuming the two boxes from Maisies are made from the same poly with similar K-, R- or U-values.

These aren’t published and I have no way of measuring them properly.

Do any readers know these having contacted the manufacturers?

Do the manufacturers even know them? They usually just quote the density of the poly if they quote anything.

It might be an interesting winter project to try and compare the relative insulation of the boxes. Perhaps placing a container holding a litre of hot water and then recording the rate of cooling might be informative?

Alternatively it might be possible to determine the amount of energy (think honey stores) needed to keep the inside of the box at a constant 30°C.

Three Everynucs and a double-decker Maisies nuc

Or perhaps not … the ‘not-beekeeping’ season here is so long I’ve got to find things to entertain me 😉 .

Of course, the boxes have to be empty before any of these measurements can be taken, so it’s convenient that I freed up a couple of nuc boxes at the beginning of the week by uniting them.

Uniting nucs

You can unite nucs with other nucs or with colonies in full hives. It depends what you want to achieve, what equipment you have to hand and where the nucs are located.

During the last round of inspections I found two nucs (in separate apiaries) without laying queens.

Actually, as far as I could ascertain, without any queens 🙁 .

Puzzling as there were queens there two weeks ago.

One of the nucs was pictured a fortnight ago. At that point it was a dummied down 5 frame colony in an 8 frame butchered Paynes poly nuc. You can’t tell from that photo (unless you understand my colony and queen numbering system) that it contained a virgin queen, but it did.

Now, as far as I can tell, it doesn’t 🙁 .

Room up top … uniting Everynucs

Since it was in a Paynes box with an integral floor I had to transfer the frames to an empty nuc brood box over a (slightly understrength as it turned out) queenright nuc. I united them with newspaper and on my next visit will shuffle the frames out that lack brood, treat them and feed them up for winter.

Fondant

The ‘recipient’ nuc, perhaps as a consequence of its strength, was short on stores. Before uniting I squeezed a kilogram or two of fondant into the integral feeder to keep them going.

It’s not unusual for colonies lacking a strong foraging force to struggle for stores if nectar isn’t in abundance.

It isn’t 🙁 .

Big, booming colonies manage to collect an excess, but smaller colonies can starve in similar conditions.

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst

The other nuc was in an out apiary and it was easier to unite them with another colony there, rather than moving them to a distant apiary and uniting with another nuc. I therefore transferred them into a spare brood box with some drawn comb before uniting them with an adjacent colony.

Ambitious? I think so.

The drawn comb is a ‘just in case’ measure.

Usually I’d just dummy down five frames in a brood box on top of a full colony.

However, that leaves an empty void in the upper brood box and there’s a faint chance the colony would fill this with brace comb in the fortnight before I next visit {{10}}.

I’m pretty certain there’s going to be no late season nectar flow, I think it’s “all over bar the shouting” in my Fife apiaries.

However ‘just in case’ I’ve given them some drawn comb to use instead.

They won’t 🙁 .

Two queens still

Attentive readers will remember I found a freshly emerged virgin queen in a colony with a – to me at least {{11}} – perfectly good 2023 clipped, marked laying queen.

Now, a fortnight later, both queens are still in the same box.

She looks fine to me

I found the marked queen on the central frames apparently laying well (at least, I observed her laying and assume the eggs on adjacent frames were probably also laid by her). I found the unmarked queen on an outer frame, scuttling around on cells filled with pollen

The usurper?

Although she was plumper and a bit less skittish I think she’s still unmated or, if mated, yet to start laying.

The weather over the intervening fortnight has certainly been good enough for queen mating, with 6-7 days over 20°C which is often quoted as the lower limit for queen mating {{12}}.

There seemed no point in intervening so I left them to get on with things and will be interested to see what has happened (if anything) by my next visit.

Winter reading

Brian Johnson’s book Honey Bee Biology has just been published by Princeton University Press. This is a scientific review of the current (and historical in places) understanding of the biology of honey bees. My copy arrived this week and I’ve dipped into it to check a few topics, but will read it carefully over the winter.

One of the topics I skimmed was supersedure and I was disappointed and relieved in equal measure to find that Johnson knows as much, or as little, as I do on the topic 😉 .

Johnson’s book is probably not recommended for those uncomfortable when faced by some some pretty heavyweight biology. He doesn’t hold back when it is necessary to discuss Notch signalling or cGMP protein kinases.

You have been warned … but if you’re still interested, NHBS have the book on special offer at the moment {{13}}.

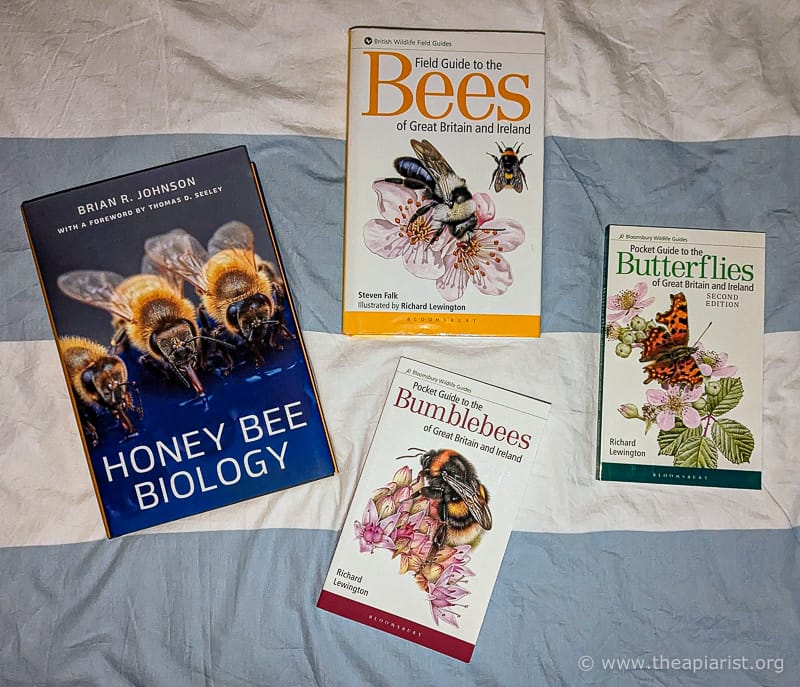

Winter reading and field guides

In the same parcel from NHBS I also received two slim Bloomsbury Wildlife Pocket Guides by Richard Lewington; to the butterflies and the bumble bees of Great Britain and Ireland. Both are beautifully illustrated and contain more than enough information to identify things you see in the apiary. The bumble bees book covers just one tenth of the bees detailed in Steven Falk’s magnum opus, the Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland {{14}}, but if you struggle to distinguish a Bombus ruderarius from a Bombus ruderatus then you’ll get the answer faster from the Lewington guide.

Something for the Christmas list perhaps?

Notes

All equipment suppliers change the specification of their products periodically. The Maisemore’s nucs I own were all purchased in the last 3 or 4 years, the green ones pictured are newer. I checked their website and it now looks as though both boxes might now have a similar roof. The brood box with the integral floor (and circular entrance disk) is a convenient design, but I’d still favour the separate floor and thick-walled brood box.

Everynucs look much the same now as when I bought them a decade or so ago. I’ve written about some of their failings previously … mostly trivial, and all surmountable. They’re great nucs.

All my Paynes boxes have the internal infernal feeder removed. They now have an entrance disk but I think the wall and roof thickness remain the same (too thin for me).

STOP PRESS

Fondant prices are steeply up this year. I think I’m paying ~50% more than I did last year, at about £18 for 12.5 kg … which means a fed/treated colony that is subsequently united or expires results in the loss of about £24 rather than the £16-17 quoted above.

Time I put my honey prices up 😉

{{1}}: Lord Mayor’s luncheon speech, 1942, responding to the Allied victory at El Alamein.

{{2}}: More on that another week.

{{3}}: You can’t tell by appearance.

{{4}}: Which I’ll know about soon as I’ve just ordered 300 kg of the stuff.

{{5}}: And, more importantly, why should I impose them on others?

{{6}}: Ageing per se is not a problem!

{{7}}: Is there any other type of church hall?

{{8}}: With apologies to any physicists or engineers … and ignoring stuff like open mesh floors, feeders etc.

{{9}}: Modernbeekeeping.

{{10}}: Ideally I’d have used a fat dummy.

{{11}}: But what the hell do I know? My bet is that the bees know best.

{{12}}: It isn’t. If it was I’d get no queens mated some summers.

{{13}}: Not an affiliate link, just a satisfied customer happy to buy from someone other than Jeff Bezos.

{{14}}: Also illustrated by Richard Lewington.

Join the discussion ...