Shallow learning curves

In principle, beekeeping is pretty simple.

You dump some bees in a box and, at the end of the season, remove frames laden with delicious honey.

The title of the first beekeeping book I bought – Bees at the bottom of the garden – vaguely hints at this level of simplicity. The title makes managing a hive sound about as complicated and involving as maintaining a compost heap {{1}}.

Is there a better example of low-maintenance, self-sufficiency?

Very Tom and Barbara Good. Few readers will appreciate this cultural reference to The Good Life (which was shown in the US with the title Good Neighbors), a 1970’s TV sitcom about a self-sufficient suburban couple. Indulge me.

Whatever the environment – a rural village, a suburban garden or a balcony on a high-rise apartment – bees provide a sort of atavistic link to simpler times.

Even with high pressure jobs, the ubiquitous internet and microwave ready-meals, we can still cling on to a tiny sliver of a more basic, and perhaps more fulfilling, existence.

Being a beekeeper means we can still provide for friends and family. Not quite a crofter but more dependable than a hunter-gatherer.

Is this why people start beekeeping?

I don’t know … and I can’t even remember why I started, though I’m pretty certain the prospect of being self-sufficient in honey was part of it.

And, of course, in principle beekeeping is pretty simple.

Shallow learning curve

A comment to last week’s post made reference to the steep learning curve associated with starting beekeeping.

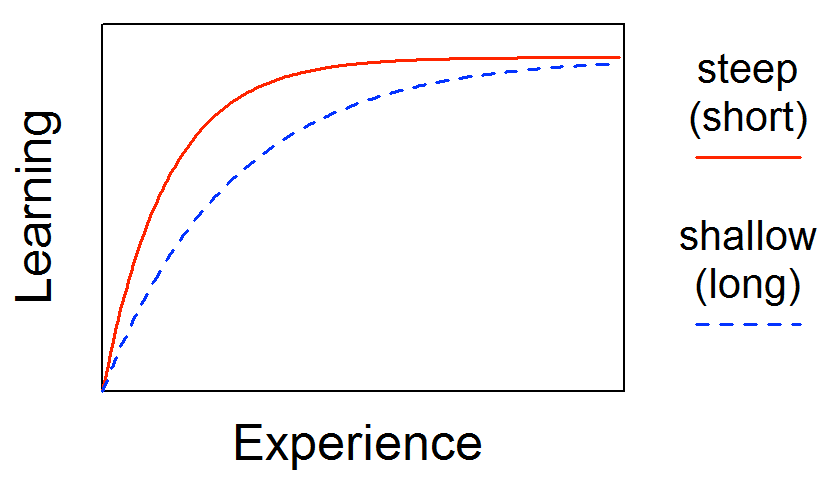

The expression ‘learning curve’ refers to the speed with which knowledge is acquired and dates back to the early 1920’s {{2}}. Specifically it indicates the shape of a line graph in which the horizontal axis represents time and the vertical axis knowledge or understanding i.e. the line shows the rate at which a task is learnt.

The word ‘steep’ first prefixed ‘learning curve’ in the 1970’s. Initially it had context-dependent meanings, either indicating tasks (like producing printed circuits) in which competence was acquired quickly, or those that were more difficult to learn, and therefore only acquired slowly.

However, by the end of the 1970’s the phrase almost always equated steepness with difficulty i.e. something with a steep learning curve is difficult to become proficient in.

Which, if you think about it, is entirely the wrong way round.

Steep hills are difficult to climb, but a steep learning curve – plotting learning vs. time (experience) – means that a lot of understanding is acquired in a short time.

In current usage a ‘steep learning curve’ means something is difficult, but it refers to the graphical representation of a task that is easily learnt.

Ben Zimmer has written a nice account of the history of the term ‘steep learning curve’ and its anachronistic appearance in Downton Abbey.

Anyway, enough pedantry {{3}} … does beekeeping have a steep or a shallow learning curve?

“In principle, beekeeping is pretty simple”

The fundamentals of beekeeping are reasonably straightforward, at least when you read about them in a book, sitting in front of a roaring fire on a cold winter night.

With a glass of wine {{4}}.

For example, consider colony inspections.

Colony inspections

You open the box, remove the dummy board and one of the outside frames to give you some space to work. Then, carefully, you remove each frame in turn looking for whatever it is you opened the box to look for in the first place.

Which might be evidence for a laying queen, or the strength of the colony, or the presence of queen cells, or signs of Varroa … or, most likely, several of those things.

And – quite possibly – other things as well.

Is fresh nectar present? What about pollen? Is the laying rate of the queen increasing or decreasing? Does the colony have sufficient space to expand? If it rains for a week does the colony have enough stores to survive?

And don’t forgot the appearance of the larvae or looking for worryingly perforated cappings, the number and position of eggs in the cells, play cups, brace comb, chalkbrood … or mice.

Assuming the frame you removed at the start contained stores that still leaves 10 frames to inspect, on both faces, all the time muttering “eggs, larvae, sealed brood, stores, queen cells, pollen etc” while trying to remember what you’ve seen already and what has yet to appear (or not).

One thing you do quickly learn is that spending too long doing all this can agitate the bees, and re-opening a box to go back and check something you thought your saw, probably agitates them even more.

Bees everywhere

So, in principle, colony inspections are easy.

But in practice they’re not.

There’s a lot to look for and a lot to remember. The problem is compounded by the large number of bees in the box. They obscure the comb, making it tricky to spot queen cells, or dodgy-looking larvae, or mispositioned eggs or – if the box is really busy – the frame lugs.

Fortunately, mice are usually easy to spot; they tend to launch themselves from the entrance – as if jet propelled – as you open the lid, but evidence of their presence is obvious visually and by smell {{5}} .

Yes, you can shake all the bees off the frames into the brood box, but you then have to repeat the mantra “eggs, larvae, sealed brood, stores, queen cells, pollen etc” or whatever from the centre of a whirling maelstrom of flying bees.

Many beginners, unsurprisingly, find this a bit distracting.

But, with experience i.e. more boxes opened, better planning and preparation, things become a lot easier.

Only open the hive when you need to. Have a clear idea of what you are looking for, remembering that it doesn’t need to be everything on the list every time.

Early in the season look for the colony building up, by mid/late May your priority should be queen cells and swarming, June or July is a good time to do a thorough disease inspection (during which you do shake all the bees off the frames) and so on.

Don’t try and do everything, focus on the priorities.

And, with experience and good observation, you’ll start to notice other – less obvious – things.

So, if colony inspections are more difficult than they sound in the books, what about something more mission-critical?

Swarm control

By mission-critical I mean something that, if omitted altogether, is likely to result in the loss of a swarm.

Not a disaster when compared with a meteor strike or missing the flight to New York, but it will reduce the likelihood of having any of those ‘frames laden with delicious honey’.

Most swarms perish, so a lost swarm also means the unnecessary death of a large number of bees … together with the potential irritation/fright that the swarm causes civilians (i.e. non-beekeepers) who encounter it.

I’ve done lots of inspections with local beekeepers during our research. It wasn’t unusual to open a hive and find half a dozen – big, fat and obvious – sealed queen cells, no eggs or larvae (but ample sealed brood) and, on breaking the bad news to the beekeeper, get the response “I checked them a week ago. They were fine.”

No, they weren’t.

Or – disappointingly – “I’ve been away walking the Camino de Santiago for six weeks. They were OK when I left!”

Again, in principle, swarm control is very easy. However, it requires good observational skills and an appreciation of the development cycle of the queen.

You need to be able to identify a colony likely to swarm (e.g. overcrowded) and those intent on swarming (i.e. charged queen cells).

You then usually need to find all the queen cells and the queen, separating the latter and leaving just one of the former {{6}}.

Not rocket science, but not necessarily straightforward for the inexperienced.

Swarm control is further complicated by the variety of different methods that can be used.

Seasonal and geographic variation

And, if that wasn’t enough, the other thing that adds confusion – particularly for beginners – are seasonal and geographic variations.

Seasonal meaning that this year was different from last – cold, late springs, wet summers, droughts, early frosts etc.

Geographic meaning that increases in latitude {{7}} shorten the season; swarming starts later, winter preparations sooner. The same applies to high altitude beekeeping.

I’ve discussed both of these points extensively before so won’t regurgitate them again.

The consequence of this seasonal and geographic variation is that a calendar is of little use in predicting or planning when things need to be done with your bees.

My comment above – ‘by mid/late May your priority should be queen cells and swarming’ – is correct here in the lowlands of eastern Scotland in an average year. However, it’s a month late for beekeepers in the south of England, and a month early for my bees on the cooler, wetter, west coast of Scotland.

Many beekeeping books or websites singularly fail to make clear just how significant this variation is, even across a country as small as the UK.

For North America the variation is even more marked.

However, despite colony inspections and swarm control (and everything else I don’t have time to discuss) being more complicated than they appear from books or the Start Beekeeping course you attended in the winter, your first season of beekeeping is often relatively straightforward.

A gentle introduction

Although far from universal, your first season of beekeeping is often a little easier than the second or third.

You purchase a healthy nuc headed by a ‘current year’ queen. She’s young, fecund and bulging with pheromones. There’s little chance the colony will swarm as long as you give them enough space.

Your first fumbling inspections are on the relatively small colony, making everything a little more obvious. Your skills improve as the colony expands.

The queen lays well and – like the Duracell bunny – just keeps on going. Lovely slabs of brood fill the hive by early summer. You missed the spring honey crop but the summer yields lots of those ‘frames laden with delicious honey’.

Christmas is sorted for friends and family (if you don’t eat it before then).

And, not only does she lay well during the summer, but she keeps on laying into early autumn … and later. Young queens do this. It’s a compelling reason why late season requeening is favoured by some beekeepers. The colony ends the season very strong and looks good for the winter ahead.

Despite all this brood rearing, Varroa levels are reasonable. Certainly higher than ideal, but probably not so high that it threatens the survival of the colony. If you look at many of the early studies of the impact of Varroa colonies perish in their second or third year, rather than the first.

And these ‘reasonable’ mite levels are fortunate as you were so keen to maximise the summer honey crop that you delayed miticide treatment. By leaving it late you inevitably damage the longevity of the winter bees … but you’ll probably get away with it.

The Dunning-Kruger effect

Your first year is over.

You’ve still got your bees and you produced some honey.

This beekeeping malarky is easier than some of those pessimistic bloggers suggest.

You might even think “I’m a pretty competent beekeeper”.

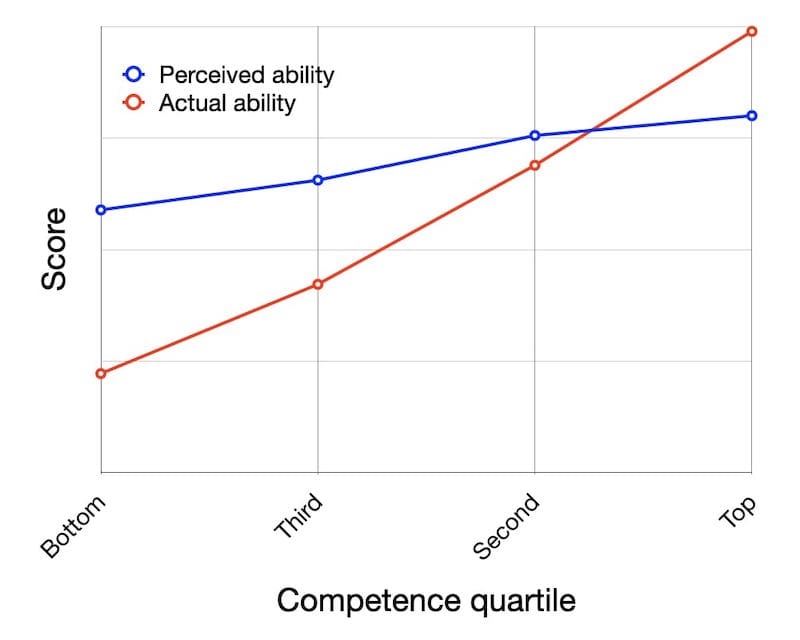

Let me introduce you to the Dunning-Kruger effect … and another graph.

This isn’t the usual graph you’ll see if you search the web for Dunning-Kruger. It is a reproduction of Figure 1 in the original paper by Justin Kruger and David Dunning (Kruger and Dunning, 1999) {{8}} that described the phenomenon.

Essentially the graph plots the actual and perceived scores (abilities) of individuals in a group – on the vertical axis – ranked according to their competence (horizontal axis) in the activity being tested.

It doesn’t matter what the activity being tested is as long as the competence in that activity is what is used for ranking the individuals horizontally.

For our purposes the activity is beekeeping, but it could be computer programming or breadmaking or – as Dunning and Kruger first used – the ability to perceive what is funny.

As Kruger and Dunning (1999) stated:

People tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains … this overestimation occurs, in part, because people who are unskilled in these domains suffer a dual burden: Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it.

Unskilled individuals tend to think they are better at an activity than they really are.

What’s more, their lack of experience means they do not realise the errors they make.

Conversely

Skilled individuals, those with ample experience in an activity, perceive themselves to be less skilled than they really are. When objectively tested, they do better than they think they have done.

Dunning-Kruger isn’t about intelligence per se, though it’s often presented in that way with peaks on the graph labelled ‘Mount Stupid’. These graphs often depict tyros perceiving themselves as being better than the experts {{9}} … perhaps this is true in some cases, but it is not universal.

The graph above better represents the false sense of security you are lulled into if you have relatively little experience in an activity – like your first year or two of beekeeping.

Don’t let it go to your head.

Your first season may well have been a little bit easier than a ‘normal’ year. The relatively late start with a good quality nuc gave you some leeway in terms of miticide treatment and made your first few inspections easier and therefore a better learning experience.

But there will be challenges in the future.

My conversations with beekeeping associations suggest many experience a high ‘drop out’ rate of recent trainees. They might get the bees through their first winter, but the colony ‘swarms out’ the following year, goes into the next winter too weak, mite-infested and perishes.

Enthusiasm wanes. They might get another nuc, but – in practice – many do not. The boxes and beesuit languish in the shed. Although once a beekeeper, the many challenges of the hobby prevents the retention of the ‘keeper’ bit in the title. They are now beehadders.

But, it doesn’t have to be like this.

Good mentoring, continued training, an appreciation of the importance of learning by observation and an understanding that the learning curve for beekeeping is shallow.

Challenges

I’ve been keeping bees for over 15 years. Because I was fortunate enough to work with bees in my career and as a hobby I’ve managed an annual average of ~20 colonies over that period {{10}}.

After these 300 ‘hive years’ – perhaps 4-5 thousand colony inspections – I’m still learning. I’m nowhere near the right hand side of the Dunning-Kruger graph, but I have enough experience to realise how much I don’t yet understand.

Every season – by which I mean Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter – I usually discover something new, or – more likely – experience something new without necessarily understanding it.

When going through my colonies last week, removing the Apivar strips and remnants of any unfinished fondant, one colony had apparently failed.

The queen was from this summer, the brood remnants were worker, she had stopped laying (and disappeared altogether), worker numbers had massively reduced {{11}}, the fondant was unfinished and the brood box was light.

At the last inspection in late August I had noted that the queen was laying really well and had an excellent brood pattern.

Not any more.

I’ve no idea what happened.

Whilst that example was disappointing, the continuing challenge of understanding the consequences of the complex interplay of an amazing social insect and the variable weather and environment ensure that beekeeping remains an engrossing obsession.

Basic understanding and unanswered questions

I think I understand the basics; I lose few swarms, successfully overwinter over 90% of my colonies, rear all my own queens, produce many more bees than I need and – with the exception of this summer – generate a surplus of honey.

However, I’m well aware there’s a huge heap of stuff I don’t understand.

Why do apparently identical colonies sometimes behave wildly differently? Two of mine, sharing a stand and headed by sister queens were of similar strength in mid/late May. One needed prompt early swarm control but the other ploughed on regardless, never produced a queen cell and just got taller and taller with the added supers.

I know, I know, the answer is probably genetics.

A little later in the summer I had some success using ‘enforced supersedure’. Briefly, I added mature, foil-protected queen cells to queenright colonies and successfully replaced the original queen. It worked, but I’m still not sure I understand how or why.

Does this recapitulate ‘true’ supersedure, or just look a bit similar? Was I lucky, or is this a really dependable method? Roger Patterson claims ~80% success rate. Why only 80%? What goes wrong 20% of the time?

Was there a brood break or do the laying queens overlap?

80% is probably acceptable, but it would be good if it was higher. It’s a great way to requeen a colony without having to fiddle with introduction cages or bother finding and removing the incumbent.

And remember those fainting queens? Some recover, some don’t. Fainting might be well be genetic … but what possible use is it to the queen? Is there an evolutionary benefit, or is it a consequence of something else?

Keep looking and don’t stop asking questions

I was out cycling yesterday on a cold, frosty morning. I stopped to take this photo and noticed a few dozen tiny (<1 mm) flying insects. My bees at home were very much clustered and definitely not flying. On a marginally warmer day this week, the colonies I’d removed the Apivar strips from had been extremely reluctant to fly.

How does a tiny insect with a very large surface area to volume ratio get and keep warm enough to fly, whereas a huge (relatively, perhaps ~2000 times the volume) bee huddled at ~34°C with a few thousand others does not?

Perhaps this is a “tiny fly conundrum”, not a beekeeping question?

More generally, what determines when and if bees fly on a cool day, and which bees in the colony fly? It’s only a very small proportion of them.

Because, for the next few months, all we’ve got are cooler days … and ample time to think about our bees and beekeeping.

Enough cod psychology … the principles of beekeeping are easy, the practice is not. Beekeeping has a shallow learning curve which – to my mind at least – may well be infinite. The more I discover the less I realise I know.

That’s not a bad thing.

Your first season might be easier than you expect. I hope it was. However, don’t become overconfident.

The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club.

Challenges await, embrace them.

Notes

Is there a better example of low-maintenance self-sufficiency?

I posed this question in the introduction.

There is … composting with worms.

Fractionally easier than the easiest beekeeping you’ll ever do. You use the ‘worm farm’ to turn the majority of your household plant-based food waste – carrot peelings, banana skins etc. as well as quite a bit of shredded newspaper or cardboard – into excellent rich compost and liquid plant food.

You dump some worms in a box, pile in the peelings and return to harvest the ‘black gold’ compost periodically, and the liquid runoff frequently.

But, like beekeeping, there are some wrinkles … don’t overfeed them, protect them from hard frosts, be prepared to control fruit fly infestations etc.

Read all about it on my sister website The WormComposter.

References

Kruger, J., and Dunning, D. (1999) Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1121–1134. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

{{1}}: The contents (With the exception of the omission of any real mention of Varroa in my edition) made clear there was a bit more to it than that.

{{2}}: Where it referred to studies by psychologists of rats navigating a maze.

{{3}}: An oxymoron?

{{4}}: Is this not the very best sort of homework?

{{5}}: Ewww!

{{6}}: There are ways of doing swarm control without finding the queen.

{{7}}: Northern hemisphere, my Antipodean readers will be used to translating appropriately.

{{8}}: Why is it called Dunning-Kruger when the paper is by Kruger and Dunning? Kruger was the PhD student, Dunning the academic supervisor … enough said!

{{9}}: I’m deliberately not going to discuss internet discussion forums here!

{{10}}: I’ve got about 30 going into this winter.

{{11}}: There’s usually a big die off of summer workers at this time of the season, but these hadn’t been replaced by winter bees.

Join the discussion ...