"Start beekeeping" courses

It’s mid-January. If you are an experienced beekeeper in the UK you’re being battered by the remnants of Storm Brendan and wondering whether the roofs are still on your hives.

If my experience is anything to go by, they’re not 🙁

But if you’re a trainee beekeeper you may well be attending a course on Starting Beekeeping, run by your local beekeeping association. Typically these run through the first 1- 3 months of the year, culminating in an apiary visit in April.

Sometimes a not-really-warm-enough-to-be doing-this apiary visit in April 🙁

Beekeeping, just like driving a car

Many years ago I attended the Warwick and Leamington Beekeepers Introduction to Beekeeping course. It was a lot of fun and I met some very helpful beekeepers.

But I learnt my beekeeping in their training apiary over the following years; initially as a new beekeeper, and subsequently helping instruct the cohort of trainees attending the course and apiary sessions the following year(s).

Teaching someone else is the best way to learn.

The distinction between the theoretical and practical aspects of the subject are important. You can learn the theory in a classroom, refreshed with tea and digestive biscuits, with the wind howling around outside.

However, it is practical experience that makes you a beekeeper, and you can only acquire these skills by opening hives up – lots of them – and understanding what’s going on.

Some choose never to go this far {{1}}, others try but never achieve it. Only a proportion are successful – this is evident from the large number who take winter courses compared to the relatively modest growth in beekeeper numbers (or association memberships).

Beekeeping is like driving a car. You can learn the theory from a book, but that doesn’t mean you are able to drive. Indeed, the practical skills you lack may mean you are a liability to yourself and others.

Fortunately, the consequences of insufficient experience in beekeeping are trivial in comparison to inexperienced drivers and road safety.

Theoretical beekeeping

What should an ‘introduction to beekeeping’ course contain?

Which bits are necessary? What is superfluous?

Should it attempt to be all encompassing (queen rearing methods, Taranov swarm control, Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus) or pared back to the bare minimum?

Who should deliver it?

I don’t necessarily know, but for a variety of reasons I’ve been giving it some thought(s) … and here they are.

The audience and the intended outcome

You have to assume that those attending the course know little or nothing about bees or beekeeping. If you don’t there’s a good chance some of the audience will be alienated before you start {{2}}.

When I started I had never seen inside a beehive. I don’t think I even knew what a removable frame was. Others on the course had read half a dozen books already. Some had already purchased a hive.

Some even had bees (or ‘hoped they were still alive’ as it was their first winter) 😯

I felt ignorant when others on the course were asking Wouldn’t brood and a half be better? or I’ve read that wire framed queen excluders are preferable.

What’s a queen excluder?

By working from first principles you know what has been covered, you ensure what is covered is important and you keep everyone together.

Some on the course like the idea of keeping bees, but will soon get put off by the practicalities of the discipline. That doesn’t mean they can’t still be catered for on the course. It can still be interesting without being exclusive {{3}}.

But, of course, the primary audience are the people who want to learn how to keep bees successfully.

For that reason I think the intended outcome is to teach sufficient theory so that a new beekeeper, with suitable mentoring, can:

- acquire and house a colony

- inspect it properly

- prevent it swarming, or know what to do if it does

- manage disease in the colony

- prepare the colony for winter and overwinter it successfully

The only thing I’d add to that list is an indication of how to collect honey … but don’t get their hopes up by discussing which 18 frame extractor to purchase or how to use the Apimelter 😉

Course contents

I’m not going to give an in-depth breakdown of my views of what an introduction to beekeeping course should contain, but I will expand on a few areas that I think are important.

The beekeeping year and the principles of beekeeping

I’d start with an overview of a typical beekeeping year. This shouldn’t be hugely detailed, it simply sets out what happens and when.

It provides the temporal context to which the rest of the course can refer. It emphasises the seasonality of beekeeping. The long periods of inactivity and the manic days in May and early June. It can be quite ‘light touch’ and might even end with a honey tasting session.

Or mead … 😉

‘Typical’ means you don’t need to qualify everything – if the spring is particularly warm or unless there’s no oil seed rape near you – just focus on an idealised year with normal weather, the expected forage and the usual beekeeping challenges.

But this part of the course should also aim to clearly emphasise the principles and practice of beekeeping.

Success, whether measured by jars of honey or overwintered colonies, requires effort. It doesn’t just happen.

Hive inspections are not optional. They cannot be postponed because of family holidays {{4}}, weekend breaks in Bruges, or going to the beach because the weather is great.

Quite the opposite. From late April until sometime in July you have to inspect colonies at weekly intervals.

Whatever the weather (within reason).

Not every 9-12 days.

Not just before and when you return from a fortnight in Madeira 🙁

And hive inspections involve heavy lifting (if you’re lucky), and inadvertently squidging a few bees when putting the hive back together, and possibly getting stung {{5}}.

The discussion of the typical year must mention Varroa management. This is a reality for 99% of beekeepers and it is our responsibility to take appropriate action in a timely manner (though the details of how and when can be saved for a later discussion of disease).

Finally, this part of the course should emphasise the importance of preparing colonies properly for the winter. This again necessitates mentioning disease control.

By covering the principles and practice of a typical year in beekeeping the trainee beekeepers should be prepared from the outset for the workload involved, and have an appreciation for the importance of timing.

We have to keep up with the bees … and the pace they go (or grow) at may not be the same every year, or may not quite fit our diaries.

Bees and beekeeping

There is a long an interesting history of beekeeping and an almost limitless number of fascinating things about bees. Some things I’d argue are essential, others are really not needed and can be safely ignored.

Bee boles in Kellie Castle, Fife, Scotland … skep beekeeping probably isn’t an essential course component.

Of the essential historical details I’d consider the development of the removable frame hive is probably the most important. Inevitably this also involves a discussion of bee space – a gap that the bees do not fill with propolis or wax. Of course, bee space was known about long before Langstroth found a way to exploit it with the removable frame hive.

The other historical area often covered is the waggle dance, but I’d argue that this is of peripheral relevance to beekeeping per se. However, it could be used to introduce the concept of communication in bees.

And once the topic turns to bees there’s almost no limit what could be included. Clearly an appreciation of the composition of the colony and how it changes during the season is important. This leads to division of labour and the caste system.

It also develops the idea of the colony as a superorganism, which has a bearing on swarm preparation, management and control.

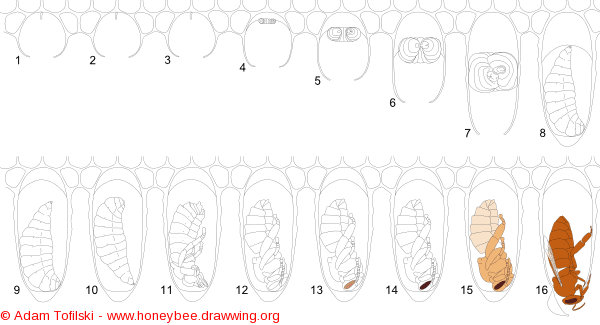

Probably most important is the development cycle of the queen, workers and drones. A proper understanding of this allows an appreciation of colony build-up, the timing of swarming and queen replacement, and is very important for the correct management of Varroa.

As with the beekeeping year, sticking to what is ‘typical’ avoids confusion. No need to mention laying workers, two-queen hives, or thelytokous parthenogenesis.

Keep on message!

Equipment

What a minefield?!

As long as the importance of compatibility is repeatedly stressed you should be OK.

A little forethought is needed here. Are you (or the association) going to provide your beginners with bees?

I’d argue, and have before, that you really should.

Will the bees be on National frames? 14 x 12’s? One of several different Langstroth frames? Smiths?

Or packages?

I said it was a minefield.

Beginners want to be ready for the season ahead. They want to buy some of that lovely cedar and start building boxes. They need advice on what to buy.

What they buy must be influenced by how they’re going to start with bees. One of the easiest ways around this is to allocate them a mentor and let them lead on the specifics (assuming they’ll be getting bees from their mentor).

One thing that should be stressed is the importance of having sufficient compatible equipment to deal with swarming (which we’ll be coming to shortly).

My recommendation would be to buy a full hive with three supers and a compatible polystyrene nucleus hive. In due course beginners will probably need a second hive, but (if you teach the simplest form of swarm control – see below) not in the first year. A nuc box will be sufficient.

Swarming and swarm control

Swarming is often considered to be confusing {{6}}.

It doesn’t need to be.

The life cycle of the bee and the colony have been covered already. Swarming and queen cells is just honey bee reproduction … or it’s not swarming at all but an attempt to rescue the otherwise catastrophic loss of a queen 🙁

Deciding which is important and should influence the action(s) taken.

The determinants that drive swarming are reasonably well understood – space, age of the queen etc. The timing of the events, and the importance of the timing of the events leading to swarming is very well understood.

Preventative measures are therefore easy to discuss. Ample space. Super early. Super often.

It’s swarm control that often causes the problem.

And I think one of the major issues here is the attempts to explain the classic Pagden artificial swarm. Inevitably this involves some sort of re-enactment, or an animated Powerpoint slide, or a Tommy Cooper-esque “Glass, bottle … bottle, glass” demonstration {{7}}.

Often this is confounded by the presenters’ left and right being the audiences right and left.

Confused? You will be.

Far better to simply teach a nucleus hive-based swarm control method. Remove the old queen, a frame of emerging brood, a frame of stores and a few shakes of bees. Take it to a distant apiary (or block the entrance with grass etc. but this adds confusion) and leave a single open charged queen cell in the original hive.

This method uses less equipment, involves fewer apiary visits, but still emphasises the need for a thorough understanding of the queen development cycle.

And, to avoid confusion, I wouldn’t teach any other forms of swarm control.

Yes, there are loads that work, but beginners need to understand one that will always work for them. Hopefully they’ve got dozens of summers of beekeeping ahead of them to try alternatives.

I think swarm control is one area where the KISS principle should be rigorously applied.

Disease prevention and management

Colony disease is a reality but you need to achieve a balance between inducing paranoia and encouraging complacency.

This means knowing how to deal with the inevitable, how to identify the possible and largely ignoring the rest.

The inevitable is Varroa and the viruses it transmits. And, of at least half a dozen viruses it does transmit, only deformed wing virus needs to be discussed. The symptoms are readily identifiable and if you have symptomatic bees – and there can be no other diagnosis – you have a Varroa problem and need to take action promptly.

In an introductory course for new beekeepers I think it is inexcusable to promote alternate methods of Varroa control other than VMD-approved treatments.

And, even then, I’d stick to just two.

Apivar in late summer and a trickle of Api-Bioxal solution in midwinter.

Used properly, at the right time and according to the manufacturer’s instructions, these provide excellent mite management.

Don’t promote icing sugar shaking, drone brood removal, small cell foundation, Old Ron’s snake oil or anything else that isn’t documented properly {{8}}.

Almost always there will be questions about treatment-free beekeeping.

My view is that this has no place in a beginners course for beekeepers.

The goal is to get a colony successfully through the full season. An inexperienced beekeeper attempting to keep bees without treatment in their first year is a guaranteed way to lose both the colony and, probably, a disillusioned trainee beekeeper from the hobby.

To lose one may be regarded as a misfortune, to lose both looks like carelessness. {{9}}

Once they know how to keep bees alive they can explore ways to keep them alive without treatment … and they will have the experience necessary to make up for the colony losses.

In terms of other diseases worth discussing then Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus (CBPV) is rapidly increasing in prevalence. Again the symptoms are pretty characteristic. Unlike DWV and Varroa it’s not yet clear what to do about it. Expect to see more of it in the next few years.

Nosema should probably be mentioned as should the foulbroods. The latter are sufficiently uncommon to be a minor concern, but sufficiently devastating to justify caution.

By focusing on the things that might kill the colony – or result in it being destroyed 🙁 – you’re obviously only scratching the surface of honey bee pests and pathogens. But it’s a start and it covers the most important things.

Most beginners have colonies that never get strong enough for CBPV to be a problem. Conversely, their weakness means that wasps might threaten them towards the end of the season, so should probably be discussed.

And, of course, the Asian hornet if you’re in an area ‘at risk’.

My beekeeping year

By this time the beginners have an overview of an idealised beekeeping year, an appreciation of the major events in the year – swarming, disease management, the honey harvest and preparation for winter.

Sounds easy, doesn’t it?

But an ideal wrap-up session to a starting beekeeping course would be the account of a real first year from a new beekeeper.

What were the problems? How did they attempt to solve them? What happened in the end?

This asks a lot of a relatively inexperienced beekeeper. Not least of which is good record keeping (but of course, they learnt this on the course the previous year 😉 ).

However, the comparison between the ‘textbook’ account delivered during the course with the ‘sweating in a beesuit’ reality of someone standing by an open hive feeling totally clueless is very enlightening.

With sufficient preparation you could even turn it into a quiz to test what the trainees have understood.

I’ve seen several ‘starting beekeeping’ courses. All have had some of the things described above. None have had all of them. Most have included superfluous information, or in some cases, dangerous misinformation.

Which brings neatly me to the question of who should teach the course?

If you can do, if you can’t teach

Ensuring that everything is covered at the right time, avoiding duplication and maintaining the correct emphasis takes skill for one person. For a group of individuals it requires a lot of preparation and strict instructions not to drift off topic.

You might have noticed that many experienced beekeepers like to talk.

A lot.

A course handbook becomes an essential – both to help the students and as a guide to keep “on message” for the tutors.

Often it is some of the most experienced beekeepers who teach these courses.

Some are outstanding. Others less so.

Their years of experience often means they take for granted the subtleties that are critical. The difference between play cups and a 1-2 day old queen cell. A reduced laying rate by the queen. How to tell when there is a nectar flow on, and when it stops.

All of this, to them, is obvious.

They forget just how much they have learned from the hundreds of hives they have opened and the thousands of frames they have examined. They’ve reached the stage when it looks like they have a sixth sense when it comes to finding the queen.

As Grasshopper says to the old, blind master {{10}} “He said you could teach me a great knowledge”.

Possibly.

But sometimes they’ve retained some archaic approaches that should have been long-forgotten. They were wrong then, they still are. Paint your cedar hives with creosote. Use matchsticks to ventilate the hive in winter. Apistan is all you need for Varroa control.

If any readers of this post have had these suggested on a course they are currently attending then question the other things that have been taught.

Get a good book that focuses on the essentials. I still think Get started in beekeeping by Adrian and Claire Waring is the best book for beginners that I’ve read {{11}}.

Get a good mentor … you’re going to need one.

And good luck!

{{1}}: A minor but significant proportion of attendees on these courses decide never to get bees (sometimes even before they finish the course or stand beside an open hive).

{{2}}: This has a bearing on the Who should deliver it? question.

{{3}}: In fact, I’d argue that a good introduction to beekeeping should still be informative and entertaining to those who decide not to pursue it as a hobby.

{{4}}: Unless you go to New Zealand in November.

{{5}}: Far better that the course encourages some not to get bees than – through a lack of awareness of what is really involved – to get bees and let them perish.

{{6}}: There were definitely no charged queen cells last week … where on earth did all these capped cells come from?

{{7}}: I wish there was a higher resolution version of this video.

{{8}}: With the exception of Ron’s snake oil (which doesn’t exist as far as I’m aware) all of these probably do not work, or if they work at all they don’t work well enough. Why teach something that doesn’t work well enough?

{{9}}: With apologies to Oscar Wilde who was referring to parents.

{{10}}: From the TV series (1972-75) Kung Fu. You had to be there.

{{11}}: But I’ve not read them all and there are ever-increasing numbers of them.

Join the discussion ...