The memory of swarms

I’m writing this waiting for the drizzle to clear so I can go to the apiary and make up some nucs for swarm control. Without implementing some form of swarm control it’s inevitable that my large colonies will swarm {{1}}.

Swarming is an inherently risky process for a colony. Over 75% of natural swarms perish, often because they do not build up strongly enough to overwinter successfully.

As a mechanism for reproduction swarming is somewhat unusual in that the intact colony is split into two not fully functional ‘halves’ {{2}}.

By not fully functional I mean that neither the swarmed colony, nor the swarm are guaranteed to survive.

The swarmed colony lacks a queen, but has ample stores.

The swarm has a queen but has only the stores carried in the bellies of the workers.

The swarmed colony needs to rear a new queen. The swarm needs to find a new nest site, move there, build comb, rear brood, forage etc.

That seems like the very opposite of intelligent design, but it’s the way evolution has made things work. This being the case it involves a whole range of compromises and quick fixes that make it work.

One of these involves the memory of worker bees, which is what this post is about.

Two-stage swarming

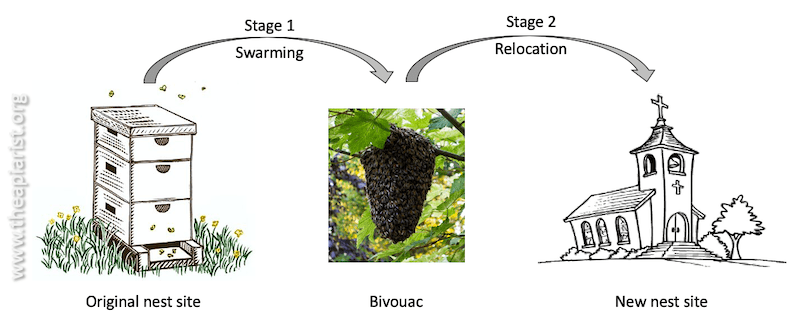

A range of events within the hive – which for reasons that will become obvious I will term the original nest site – trigger the urge to swarm. I discussed some of these when covering swarm prevention. Swarming is then essentially a two-stage process.

The first stage is the swarm leaving the original nest site and establishing a bivouac nearby. This is the classic cluster of bees hanging from a branch.

The bivouac sends out scout bees to search the nearby area for potential new nest sites. After ‘discussion’ (comprehensively covered by Thomas Seeley in Honeybee Democracy) between the scouts they reach a consensus of the best site.

The second stage is the relocation of the bivouacked colony to the new nest site. For example, this could be the church tower, a hollow tree or a bait hive. This site is likely to be within a few hundred metres of the original nest site, but can be further away.

All of which should raise some questions in the minds of beekeepers who are familiar with the “less than 3 feet or more than 3 miles” rule.

Have these bees not read the rules?

If you want to move a hived colony of bees you’ll often be told, or have read, that you need to move them either less than three feet or more than 3 miles.

Worker bees have a foraging range of about 3 miles. Within this range they have an uncanny ability to return to the hive location using features of the landscape to orientate themselves. The ‘final approach’ uses scent from the hive entrance.

Therefore, if you move a colony 3 feet they’ll still find the general location using landscape features, and then orientate to the hive entrance using scent.

If you move a colony 10 miles away everything is new to them and they’ll embark on some orientation flights to learn the new landscape features.

But if you move the colony a mile they’ll use the landscape features to return to the site of the original hive … to find it gone 🙁 {{3}}

Swarms break all these rules.

The bivouac is (in my experience) always more than 3 feet from the hive entrance. If the scout bees make the choice (e.g. selecting a bait hive to occupy), the swarm always relocates to a new nest site less than three miles from the site it left {{4}}.

And a beekeeper who drops a bivouacked colony into a skep can move it wherever she wants, even back to the same hive stand it recently vacated.

If the swarm followed the rules, the majority of the workers would return from the bivouacked swarm to the original nest site.

At least they would if they had orientated to the original nest site in the first instance.

Are the bees naive?

About half of a workers life is spent as a forager collecting water, pollen or nectar. But before they venture out of the hive, the first half of a worker bees life is spent building comb, nursing larvae or cleaning cells.

Therefore, one possibility is that the bees present in a swarm have no knowledge of the hive location because they’ve never before left the hive.

We know that the proportion of workers that leave the colony when it swarms is about 75%. This has been determined in a number of independent studies and is remarkably consistent, irrespective of the size of the colony that swarms.

If 75% of the workers leave the colony when it swarms it is mathematically impossible for the swarm not to include older foragers (assuming the laying rate of the queen is steady).

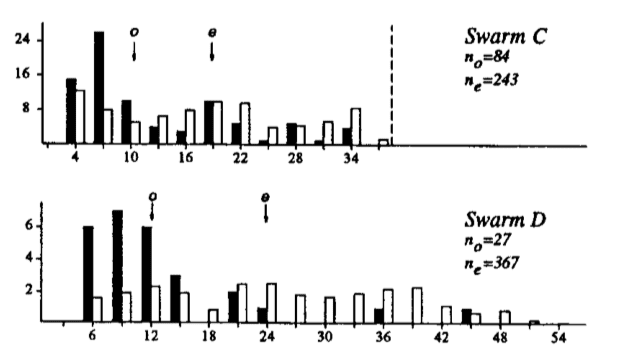

In fact, we don’t need to resort to any underhand mathematics as the age classes of bees in a swarm have been measured. I’ve discussed this before when comparing natural and artificial swarms.

The median age of adult bees in the hive is 19 days. The median age of bees in a swarm is 10 days. Therefore swarms do contain younger bees, but not exclusively so.

One of the reasons for this bias towards younger bees must be to do with the relatively short lifespan of foragers. Many of the older bees in the swarm will have perished long before the new brood laid by the queen emerges.

Permanent amnesia?

The bivouacked swarm doesn’t dwindle in size as the older foragers drift back to the original nest site. Other than a few hundred scout bees, the majority of the bivouacked swarm huddle together to protect the queen, buried somewhere in the centre, from the elements.

They don’t fly or forage … they’re waiting for the signal from the scout bees that a new nest site has been located.

And, once they relocate to the church tower, the hollow tree or a bait hive, the older foragers stay in the new nest location. It’s as though the bees in a swarm that previously knew where the original nest site was have amnesia.

And this makes sense. If they did return to the original nest site the swarm (whether bivouacked or relocated) would shrink in size and it’s chances of surviving would be severely diminished. Other than a full belly of honey a swarm can rely on nothing. They need as many bees as possible to take on all the roles needed to establish a new colony – comb builders, nurses, foragers etc.

But have they really forgotten the original nest site?

Temporary amnesia?

It turns out that swarms do retain a memory of their original nest site.

In 1993 Gene Robinson and colleagues demonstrated that a swarm shaken out from its new nest site preferentially returns to the original nest site, rather than to an equidistant alternate {{5}}.

This ability must rely on the memory of the foragers in the swarm. Therefore it is likely to be lost in a relatively short time (days, not weeks) {{6}}.

Firstly, the foragers will be busy reorienting to the new nest site, effectively overwriting the memory of the original nest location. In good weather this takes just a couple of days.

Secondly, these ageing bees don’t have long to live, so there will be ever-decreasing numbers of them to lead a shaken out swarm back to the original location.

Rain stops play

Sometimes the bivouacked colony never relocates to a new nest site. Either the scouts never achieve a consensus or – more likely – bad weather forces the swarm to hunker down.

When you hive a bivouacked swarm you will often find a small crescent or two of new wax on the branch they were clinging to. If the bees get trapped by bad weather I think the comb building continues. It’s not unusual to find comb in hedgerows near apiaries where bees that have got trapped have ended up trying to make a new nest.

What does the memory – or lack of it – of swarms mean for practical beekeeping?

The (temporary) amnesia of swarms means you can collect a bivouacked swarm and move it wherever you want. A swarm that relocates to your bait hive can also be moved, but don’t wait too long. Within just a few days of a swarm arriving the bees will have reoriented to their new location. I always try and move bait hives to their final location within three days of a swarm appearing.

Notes

The drizzle stopped and I spent the entire day finding queens and making up nucs.

Note to self … a super-strong colony with no queen cells, wall-to-wall brood and no very young larvae or eggs probably has a faulty queen excluder 🙁

Second note to self … Sod’s law dictates that the colony with the faulty queen excluder probably has supers filled with drone comb 🙁

{{1}}: The queens are all clipped, but that’s not so much swarm control as damage limitation.

{{2}}: And, as we’ll see in a minute, it’s not divided equally either.

{{3}}: There are all sorts of tricks to circumvent this rule, but that’s not what this post is about. I’ve written about some of the tricks that can be used to move colonies intermediate distances previously.

{{4}}: More usually 200-800 metres away.

{{5}}: Robinson G E and F C Dyer (1993) Plasticity of spatial memory in honey bees: reorientation following colony fission. Animal Behaviour 46 : 311-320.

{{6}}: This is reasoned speculation – I don’t think anyone has measured this experimentally.

Join the discussion ...