Unknown knowns

If there’s one thing that can be almost guaranteed about the beekeeping season ahead it’s that it will be unpredictably predictable. I can be pretty sure what is going to happen, but not precisely when it’s going to happen.

These are the unknown knowns.

The one thing I can be sure about is that once things get started it will go faster than I’d like … both in terms of things needing attention now (or yesterday 🙁 ) and in the overall duration of the season.

So, if you know what is coming – spring build up, early nectar flow, swarming, queen rearing, splits, summer nectar flow, robbing, uniting, wasps, Varroa control and feeding colonies up for winter – you can be prepared.

As Benjamin Franklin said …

By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail

Preparation involves planning for the range of events that the season will (or could) produce.

It also involves ensuring you have additional equipment to cope with the events you’ve planned for.

Ideally, you’ll also have sufficient for the events you failed to include in your plans but that happened anyway 😉

Finally, it involves purchasing the food and treatments you need to manage the health and winter feeding of the colony {{1}} .

So what do you need to plan for?

Death and taxes {{2}}

The two utterly dependable events in the beekeeping season are – and this is likely to be a big disappointment for new {{3}} beekeepers – Varroa control and feeding.

Not an outrageous early spring honey crop, not ten weeks of uninterrupted balmy days for queen rearing, not even lots of swarms in your bait hives (freebees) … and certainly not supers-full of fabulous lime or heather honey.

Sorry 😉

So … plan now how you are going to feed the colony and how you are going to monitor and manage mites during the season.

Feeding usually involves a choice between purchased syrup, homemade syrup or fondant. I almost exclusively use fondant and so always have fondant in stock. I also keep a few kilograms of sugar to make syrup if needed.

Buy it in advance because you might need it in advance. If it rains for a month in May there’s a real chance that colonies will starve and you’ll need to feed them.

I’ve discussed mites a lot on this site. Plan in advance how you will treat after the summer honey comes off and again in midwinter. Buy an appropriate {{4}} treatment in advance {{5}}. That way, should your regular mite-monitoring indicate that levels are alarmingly high, you can intervene immediately.

Having planned for the nailed-on certainties you can now turn your attention to the more enjoyable events in the beekeeping year … honey production and reproduction.

Honey production

Preparing for the season primarily means ensuring you have sufficient equipment, spares and space for whatever the year produces.

In a good season – long sunny days and seemingly endless nectar flows – this means having more than enough supers, each with a full complement of frames.

How many is more than enough?

Here on the east coast of Scotland I’ve not needed more than three and a bit per hive i.e. a few hives might need four in an exceptional summer (like 2018). When I lived in the Midlands it was more.

Running out of supers in the middle of the nectar-flow-to-end-all-nectar-flows is a frustrating experience. Boxes get overcrowded, the bees pack the brood box with nectar, the queen runs out of laying space and the honey takes longer to ripen {{6}}.

Without sufficient supers {{7}} you’ll have to beg, borrow or steal some mid-season.

Which is necessary because … it’s exactly the time the equipment suppliers have run out of the supers, frames and foundation you desperately need.

And so will all of your beekeeping friends …

Not that you’ve necessarily got the time to assemble the things anyway 😉

Don’t forget the brood frames

You’ll need more brood frames every season. A good rule of thumb is to replace a third of these every year.

There are a variety of ways of achieving this. They can be rotated out (moving the oldest, blackest frames to the edge of the box) during regular inspections, or you can remove frames following splits/uniting or through Bailey comb changes.

Irrespective of how it’s achieved, you will need more brood frames and – if you use foundation – you’ll need more of that as well.

And the suppliers will sell out of these as well 🙁

But that’s not all …

You will also need sufficient additional brood frames for use during swarm prevention and control and – if that didn’t work – subsequent rescue of the swarm from the hedge.

Swarmtastic

In a typical year the colony will reproduce. Reproduction involves swarming. If the colony swarms you may lose the bees that would have produced your honey.

You can make bees or you can make honey, but it takes real skill and a good year to make both.

And to make both you’ll need spare equipment.

Knowing that the colony is likely to swarm in late spring, you need to plan in advance how you will manage the hive to control or prevent swarming. This generally means providing them with ample space (a second brood box … so yet more brood frames) and, if that doesn’t work {{8}}, manipulating the colony so that it doesn’t swarm.

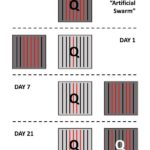

Which means an additional complete hive (floor, brood box, yet more brood frames, crownboard, roof) if you plan to use Pagdens’ artificial swarm.

Alternatively, with slightly less equipment, you can conduct a vertical split which is essentially a vertically orientated artificial swarm.

Or you can use a nucleus (nuc) box to house the old queen … a very straightforward method I’ll discuss in more detail later this season.

Bait hives and skeps

I don’t like losing swarms. I’ve previously discussed the responsibilities of beekeepers, which includes not subjecting the general public to swarms that might harm or frighten them, or establish a colony in their roof space.

But I do like both attracting swarms and re-hiving swarms of mine that ‘escaped’ (temporarily 😉 ). I always set out bait hives near my apiaries. If properly set up these efficiently attract swarms (your own or from other beekeepers) and save you the trouble of teetering at the top of a ladder to recover the swarm from an apple tree.

But if you end up doing the latter you’ll need a skep {{9}} or a nice, light, large poly nuc box to carefully drop the swarm into.

Don’t forget the additional brood frames you will need in your bait hive or in the hive you eventually place the colony in the skep into 😉

Planned reproduction

You’re probably getting the idea by now … beekeeping involves a bit more than one hive tucked away in the corner of the garden.

Not least because you really need a minimum of two colonies.

A quick peek inside the shed of any beekeeper with more than 3 years experience will give you an idea of what might be needed. Probably together with a lot of stuff that isn’t needed 😉

By planned reproduction I mean ‘making increase’ i.e. deliberately increasing your colony numbers, or rearing queens for improving your own stocks (or those of others).

This can be as simple as a vertical split or as complicated as cell raising colonies, grafting and mini mating nucs.

By the time most beekeepers get involved in this aspect of the hobby {{10}} they will have a good idea of the additional specialised equipment needed. This need not be complicated and it certainly is not expensive.

I’ve covered some aspects of queen rearing previously and will write more about it this season.

Of course, once you start increasing your colony numbers you will need additional brood boxes, supers, nuc boxes, floors, roofs, stands, crownboards, queen excluders and – of course – frames.

And a bigger shed 😉

Colophon

The title of this post is an inelegant butchering of part of a famous statement from Donald Rumsfeld, erstwhile US Secretary of Defense. While discussing evidence for Iraqi provision of weapons of mass destruction Rumsfeld made the following convoluted pronouncement:

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.

The unknown known

If you can be bothered to read through that lot you’ll realise the one thing Rumsfeld didn’t mention are the unknown knowns.

However, as shown in the image, this was the title of the 2013 Errol Morris documentary on Rumsfeld’s political career. In this, Rumsfeld defined the “unknown knowns” [as] “things that you know, that you don’t know you know.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly Condoleezza Rice, Secretary of State, claimed that Rumsfeld “doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” ... though she wasn’t referring to the unknown knowns.

{{1}}: And possibly early- or mid-season feeding as well.

{{2}}: Benjamin Franklin said this as well … Our new Constitution is now established, and has an appearance that promises permanency; but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes (1789). However, he wasn’t the first. Christopher Bullock used it 73 years earlier in ‘The Cobbler of Preston’ … ’Tis impossible to be sure of any thing but Death and Taxes.

{{3}}: And old.

{{4}}: If you live in the far north don’t stock up on Apiguard … it’s too cold to use the stuff in most seasons. If you live in an area with pyrethroid-resistant mites (you almost certainly do!) don’t buy Apistan or related fluvalinates.

{{5}}: Because you can be damn sure that the suppliers will have sold out when you really need it!

{{6}}: The bees need additional space to help evaporate the excess water off the nectar before capping off the cells.

{{7}}: For your honey production colonies. Those used for queen rearing or splitting into nucs may well need fewer.

{{8}}: When that doesn’t work, or when that stops working!

{{9}}: A traditional woven straw or wicker basket. These can be beautiful and are easy to make, but in my hands not both.

{{10}}: And many never do … which is a great shame as probably the most rewarding experience is managing a calm, healthy, productive colony headed by a queen you have raised.

Join the discussion ...