No risk, no reward

“April showers bring May flowers”, or something close to that, is a poem that has its origins in the General Prologue of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

It means that the Atlantic low pressure systems that roll in from the west during April, often bringing rain, also account for the abundance of flowers that bloom in May.

Not much sign of any April showers last month …

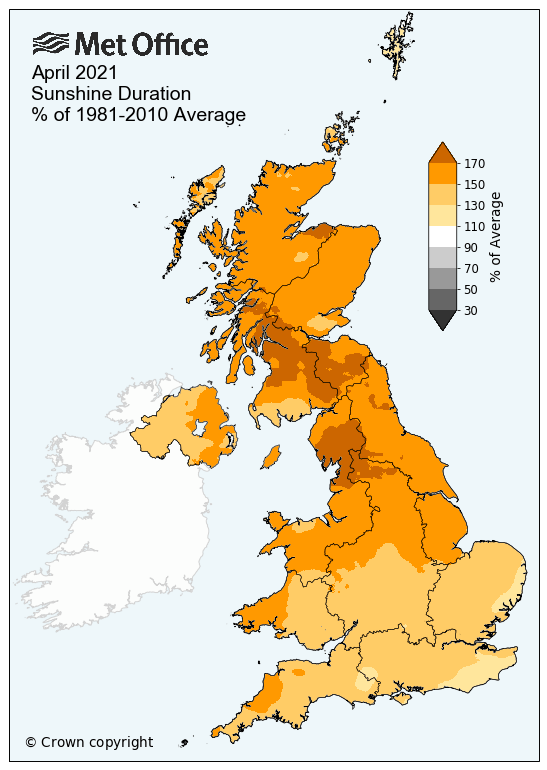

Most of the country was bathed in spring sunshine, with Scotland and the north of England getting 150-170% of the average seen over the last 30-40 years.

Unsurprisingly, with that amount of sunshine, rain was in short supply. Much of the country experienced only 20-33% of the usual April rainfall.

Which should be great for beekeeping, right?

Well, not if it’s accompanied by some of the lowest temperatures seen for half a century.

The entire country was significantly colder than normal, with the bit of Fife my bees are in being 3°C colder than the average over the last decade, with frosts on ~60% of the nights during the month {{1}}.

And, for those of us interested in queen rearing, this sort of start to the season can cause frustrating delays … or encourage a bit of risk taking.

The heady mix of strong colonies, drones and good weather

Queen rearing needs three things to occur at more or less the right time – which doesn’t mean simultaneously.

- The colony needs to be strong enough to rear new queens. Good queens – whether reared from grafted larvae or naturally under the swarming or emergency impulse – require lots of nurse bees in the hive to lavish the developing larvae with attention. Three or four frames of brood isn’t enough. The hive really needs to be bursting with bees. A long winter, cold spring or bad weather can hold the colony back.

- Drones need to be available to mate with the virgin queens. Drones take 24 days to develop from egg to emerged adult. However, before they can mate, drones need to reach sexual maturity and learn about the environment around the hive. Sexual maturity takes 6 – 16 days and, at the same time, the drones embark on a number of orientation flights which start a week or so after emergence.

- Good weather for queen mating. After emerging the queen also needs to reach sexual maturity. This takes 5-6 days. She then goes on one or more mating flights, before returning to the hive for a lifetime of egg laying {{2}}. Bad weather – either temperatures significantly below 20°C, rain or strong winds – all prevent these mating flights from taking place.

With no drones, a weak colony, or lousy weather there’s little chance of producing high quality, well-mated queens.

Or perhaps of producing any queens at all 🙁

Second impressions

My Fife colonies were first inspected in mid-April. Most were doing OK, with at least 5-7 frames of brood and some fresh nectar in the brood box.

Despite the low temperatures they were making the most of the sunshine and foraging whenever possible.

A week later, at their second inspection on the 25th, the majority of colonies had 1-2 supers {{3}} and were building up well. All had drone brood and some had adult drones.

By this time I’d identified – from my records, the overwinter performance (stores used, strength and build-up) and their behaviour when inspected under frankly rubbish conditions – which colonies I would be using for queen rearing.

I also knew which colonies would need to be requeened.

My ‘rule of thirds’

My colony selection for stock improvement is simple and straightforward.

Colonies that I consider form the worst third of my stocks are always requeened {{4}}. Furthermore, I do my best to avoid these bees contributing to the gene pool. I don’t use larvae from them for grafting and I don’t split them and allow them to rear their own queens {{5}}.

Ideally (in terms of the gene pool, not in terms of their fate 🙁 ) I’d also remove all drone brood from these colonies. These drones will most likely mate with queens from other hives {{6}}, but if their genes aren’t good enough for me they probably aren’t good enough for the unsuspecting virgin queens in the neighbourhood either.

Colonies I consider in my top one third of stocks are used as a source of larvae for grafting, and can be split and allowed to rear their own new queens.

The ‘middle’ third are requeened if I have spare queens, which I usually do.

It’s surprising how quickly this type of selection results in stock improvement. By focusing on a series of simple traits I favour (e.g. frugal with winter stores, calm when inspected in persistent rain) or dislike (e.g. running on the comb, following, stroppiness) in my bees I’ve ended up with stocks that are pretty good {{7}}.

Queen cells … don’t panic

On April 25th many colonies had play cups but only one had charged queen cells.

Considering the 10 day weather forecast, my overall level of preparedness to start queen rearing (!) and the relatively early stage of development of the cells (24-48 hour larvae) I nearly squidged the cells and closed the hive up for another week.

It still felt too early and far too cold.

I know that knocking back queen cells is not swarm control (and have suggested this is engraved on all hive tools sold to beginners).

However, swarming also requires good weather. If it’s 9-11°C the colony will not swarm … and I was pretty confident that the weather wasn’t going to warm up significantly in the week until the next inspection.

So, in my typical “Do as I say, don’t do as I do” style, I reckoned it was a safe bet to destroy the queen cells and check again a week later.

I would have expected to find more queen cells then, but I’d have been astounded if the colony had swarmed in the intervening period.

Second thoughts

But this was a lovely colony.

It has always been good, had overwintered on a single 12.5 kg block of fondant and was already on 10 frames of brood in all stages {{8}}. And that was a full box as it’s a Swienty brood box that only takes 10 National frames. To give them more room I would have had to add another brood box.

Not only that, but the bees were calm when inspected under miserable conditions. They didn’t run about on the comb and they weren’t aggressive.

The colony was comfortably near the top of my top third …

If the colony had swarmed, despite the queen being clipped, there’s a good chance I’d have lost her. The apiary is ~140 miles from home and that’s not the sort of journey you can make to ‘quickly check the hives’.

So, how could I ensure that I didn’t lose the queen and take advantage of the quality of the stock and its apparent readiness to reproduce?

Plan B

Looking after the queen was straightforward.

I prepared a 3 frame nucleus colony containing the frame the queen was on and a couple of frames of emerging brood. I added a frame of sealed stores and a new frame of foundation.

I stuffed the entrance of the nuc with grass, wedged the frames together with a foam block and pinned a travel screen over the top.

The travel screen really wasn’t necessary. I had to transport the bees to another apiary and, although there was now weak sunshine the temperature was only just double digits (°C) and my beesuit was still damp from an earlier shower. I didn’t fancy driving for 40 minutes with the windows open to keep the bees cool, so opted to ventilate them better and keep me a bit warmer 😉

This is the nucleus method of swarm control. It’s almost foolproof {{9}}.

It is possible to get it wrong, but you have to try quite hard.

In my experience it’s the most dependable method and has the added advantage of using the minimal amount of additional equipment.

The queen was safe in a new box. She had space to lay and lots of young bees to support her. The queenless colony had ample stores and 7 frames of brood in all stages.

This nucleus colony will be used as a source of larvae for grafting in mid/late May. I can easily regulate the strength of this colony – to prevent them swarming – by stealing a frame or two of brood periodically. If replaced by a foundationless frame (or a frame with foundation) they will draw lovely new comb with the help of the nectar flow from the oil seed rape.

The original, and now queenless, colony was given three new frames and closed up.

One week later

In early May the cold, sunny weather was replaced by very cold, very wet weather 🙁

On the 3rd of May I drove through snow and heavy rain to get to the apiary. The following day I started inspecting the colonies in intermittent light drizzle and a temperature of 7°C.

Not ideal 🙁

The weather gradually improved. By the time I finished in the apiary it had reached a balmy 11°C.

Notwithstanding the conditions, the bees were well behaved.

With some bees, if you open the hive in poor weather they rush out mob-handed.

Before you get a chance to think “Can I smell bananas?” you’ve collected half a dozen stings and they’re recruiting reinforcements {{10}}.

You know it’s going to be a long and painful day …

However, perhaps because the bees were sick and tired of the low temperatures this spring they just sat on the comb looking mournful … you could almost see their little faces as row upon row of upside down smilies 🙁 🙁 🙁 🙁

This ‘calmness in the face of adversity’ (!) makes these bees easy and tractable to deal with in poor conditions. It’s a byproduct of selection from the ‘best’ third of my stocks year after year.

I don’t actively select bees for bad weather beekeeping, but it’s a nice bonus when it happens.

The queenless colony now contained 7 frames of sealed brood, many of which also contained queen cells. They had almost completely drawn the new frames I’d added the previous week when I made up the nuc.

More nucs

I prepared 3 two frame nucs from the hive, leaving the remaining frames – with some new ones – in the dummied down brood box.

Doing this sort of manipulation in poor weather takes preparation and planning. You do not want to be rushing back to the shed for an extra frame, or searching around for entrance blocks, or doing anything that leaves the bees exposed for longer than necessary.

The poly nucs were all set up, with the entrances sealed, a frame of capped stores, two new frames and a dummy board. The foam travel blocks (to hold the frames tightly together), plastic crownboards, lids and hive straps were piled up within easy reach.

All of this was done before I’d even opened the queenless hive {{11}}.

The queen cells were all sealed (as would be expected from the timing of the last inspection, 8-9 days earlier) and had been produced in a busy hive, with lots of nurse bees to attend to them.

The majority would have been reared under the emergency impulse.

I quickly and carefully transferred two frames from the queenless hive to each nuc. I ensured that each nuc received a frame containing a good queen cell.

In practice, the nucs and the colony remnants probably all ended up with several queen cells.

Not another “Do as I say, don’t do as I do?” situation?

I usually leave only one queen cell in a hive to ensure a strong colony doesn’t produce multiple casts.

However, this time I did not thin out any of the queen cells.

This was a pragmatic decision largely based upon the weather. It was too cold to be searching across every frame to select the best cell. The bees would have been distressed and disturbed, and there was a risk of chilling the brood {{12}}.

It was also a rational decision considering the strength of the colonies I was setting up. With a much-reduced population of bees it’s very unlikely the colony will allow all the queens to emerge. I expect most of the cells to be torn down by the workers.

The nucs were all transferred to an apiary over three miles away. This avoids any risk of them reducing in strength due to flying bees returning to the original site.

These nucs were relatively small colonies so will require some TLC. I’ll check them soon after the new queens emerge. If they look understrength I’ll add a frame of emerging brood (harvested from one of the bottom ‘third’ of colonies. They might not be good enough to split but they are still very useful bees 🙂 ).

I’ll then leave them for at least 2-3 weeks hoping that the weather improves significantly for queen mating.

This is the ‘taking a risk’ bit of the whole process. Mid/late May should offer some suitable days for queen mating, but if this weather continues it’s not guaranteed.

Somewhere between ~26-33 days after emergence the virgin queen becomes too old to mate successfully.

For these queens, that will take us to the week beginning the 3rd of June.

If we’ve not had any good queen mating days by then things will be getting a bit desperate 🙂

Active queen rearing begins soon

Splitting a colony into nucs containing queen cells is one way of rearing new queens. The quality of the resulting colony is dependent – at least partially – on the quality of the colony you start with.

With a high quality starting stock it is effectively ‘passive’ queen rearing … very little effort with potentially good rewards.

What’s not to like?

But with the weather slowly but inexorably improving (really!) it’s time to start thinking about ‘active’ queen rearing – cell starters, grafting, cell finishers, mini-nucs etc.

With the good quality queen busily laying away in her nuc box it was time to set up a colony for queen rearing using the Ben Harden approach.

In this instance the quality of the colony is largely immaterial. It needs to be strong and healthy, but its genetics will not contribute to the quality of the resulting queens.

My final task before leaving the apiary was to add the fat dummies and additional frames in preparation for queen rearing using selected grafted larvae.

And that’s what I hope to be doing next week 🙂

{{1}}: The average is ~10%.

{{2}}: Unless she takes a temporary holiday and swarms later that year, or the following season.

{{3}}: With the strongest colonies needing the additional supers as much to house the rapidly expanding workforce as the fresh nectar.

{{4}}: Or dequeened (is that a word?) and united.

{{5}}: Note the qualifying I do my best. Inevitably there are times when my best isn’t good enough (I refer you to my school reports for ample evidence of this ;-) ) … the colony swarms and I have no suitable queens available, or no eggs/larvae from a ‘good’ colony to donate, or it supersedes ‘on the quiet’. There are few absolutes in beekeeping … other than “Knocking back queen cells is not swarm control”, though also see below.

{{6}}: … and probably other apiaries. Queens and drones fly different distances to the drone congregation areas for mating, so avoiding – or at least reducing – the risk of deleterious incestuous matings that reduce genetic diversity and hence colony fitness.

{{7}}: And since my research team – with limited experience of beekeeping – also need to use some of these bees they are acceptable to others as well.

{{8}}: … with two part-filled supers.

{{9}}: Actually, it’s the first part of the method … the second part is managing the queenless colony. I’ve described this before and was going to do something different this time.

{{10}}: The characteristic smell of bananas is due to the presence of isoamyl acetate (also called isopentyl acetate) which is the principle component in the sting apparatus alarm pheromone.

{{11}}: There’s a fourth nuc in the picture … I wasn’t sure how many I’d be making, which depended upon the colony strength and the number of queen cells.

{{12}}: And the beekeeper.

Join the discussion ...