It's a drone's life

What has a mother but no father, but has both a grandmother and grandfather?

If you’ve not seen this question before you’ve not attended a ‘mead and mince pies’ Christmas quiz at a beekeeping association.

The answer of course is a drone. The male honey bee. Drones are produced from unfertilised eggs laid by the queen, so formally they have no father. Drones are usually haploid (one set of chromosomes), whereas queens and workers are diploid {{1}}.

Anyway, enough quiz questions. With the relaxation in Covid restrictions we may all be able to attend in person this Christmas {{2}}, so I don’t want to spoil it by giving all the answers away in advance.

The long cold spring has been pretty tough for new beekeepers, it’s been a struggle for smaller colonies and it’s been really hard for drones.

Spring struggles

New beekeepers have had to develop the patience of Job to either acquire bees in the first place or start their inspections. Inevitably new beekeepers are bursting with enthusiasm {{3}} and the cold northerlies, unseasonal snow (!) and low temperatures have prevented inspections and delayed colony development (and hence the availability and sale of nucs).

Small colonies {{4}} are struggling to rear brood and to collect sufficient nectar and pollen.

This is an interesting topic in its own right and deserves a post of its own {{5}}. In a nutshell, below a certain threshold of bees, colonies are unable to keep the brood warm enough and have sufficient foragers to collect nectar and pollen.

As a consequence, smaller colonies are low on stores and at risk of starvation.

It’s a Catch-22 situation … to rear sufficient brood to collect an excess of nectar (or pollen) the colony needs more adult workers.

I don’t know what the cutoff is in terms of adult bees, but most of my colonies with <7 frames of brood have needed feeding this spring.

One feature of these smaller colonies is that, unless they have entire frames of drone comb {{6}}, there is little if any drone brood in the hive.

There might be drones present in the colony, but I don’t know whether they were reared there or drifted there from another hive.

And, for those of us attempting to rear queens, drones are an essential indicator that queen mating will be timely and successful.

On a brighter note …

But it’s not all gloom and doom.

Strong colonies are doing very well.

Several of mine have a box packed full of brood and I’m relying on a combination of …

- lots of space by giving them more supers than they need

- low ambient temperatures

- crossed fingers

… as my swarm prevention strategy 😉

Beginners take note … one of these is likely to help (space), one is frankly pretty risky (chilly) and the last is not a proven method despite being widely used by many beekeepers 😉

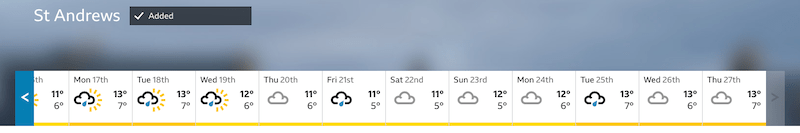

I’m pretty confident that colonies will not swarm at 13-14°C.

I am inspecting colonies every 7 days and have only seen two with charged queen cells. One was making early swarm preparations; I used the nucleus method of swarm control and then split the colony into nucs a fortnight ago {{7}}.

The other colony contained my first attempt at grafting this year, which seems to have gone reasonably well {{8}}.

A typical brood frame from one of these strong colonies contains a good slab of sealed or open brood, some pollen around the sides and an interrupted arc of fresh nectar above the brood.

In the photo above you can see pollen on the right hand side of the frame and glistening fresh nectar in the top left and right hand corners.

Typically these strong colonies also have partially filled supers, though it’s pretty clear that the oil seed rape is likely to go over before the weather warms enough (or the colonies get strong enough) to fully exploit it.

Spring honey is going to be in short supply and my fantastic new honey creamer is going to sit idle 🙁

Drones

What you probably can’t really see in the picture above is that these strong colonies also contain good numbers of drones.

I can count about a dozen in the closeup above.

I like seeing drones in a strong, healthy colony early(ish) in the season {{9}}.

Firstly, the presence of drones indicates that the colony (and presumably others in the neighbourhood which are experiencing a similar environment and climate) will soon be making swarm preparations. This means I need to redouble my efforts to check for queen cells to avoid losing swarms 🙁 … think of it as a long-range early warning system.

But it also means I can start thinking about queen rearing 🙂

Secondly, although these drones are unlikely to mate with my queens, you can be sure they’re going to have a damned good go at mating with queens from other local apiaries.

In addition to being strong and healthy, this colony is well-tempered, steady on the comb and pleasant to work with. The production of a few hundred thousand frisky drones prepared to lay down their lives {{10}} to improve the local gene pool is my small act of generosity to local beekeepers {{11}}.

How many drones?

Honey bee colonies that nest in trees or other natural cavities produce lots of drone comb. Studies of feral colonies on natural comb show that about 17% of the comb is dedicated to rearing drones (but also used for storing nectar at other times of the season).

Similarly, beekeepers who predominantly use foundationless frames regularly see significantly greater amounts of drone comb (and drone brood and drones) in their colonies. With the three-panel bamboo-supported frames I use it’s not unusual for one third of some frames to be entirely drone comb.

In contrast, beekeepers who only use standard worker foundation will be used to seeing drone comb occupying much less of the brood nest. Under these circumstances it’s usually restricted to the edges or corners of frames.

However, given the opportunity e.g. a damaged patch of worker comb or if you add a super frame into the brood box, the workers will often rework the comb (or build new brace comb) containing just drone cells.

The bees only build drone comb when they need it.

A newly hived swarm will build sheet after sheet of new comb, but it will all be for rearing worker brood. If you give them foundationless frames they only build worker comb and if you provide worker foundation they don’t rework it to squeeze in a few drone cells.

The colony will also not build new drone comb late in the season. Drone comb is drawn early in the season because the drones are needed before queens are produced.

The timing of drone production

Studies in the late 1970’s {{12}} demonstrated that drone brood production peaks about one month before the the main period of swarming. Similar studies in other areas have produced similar results.

Why produce all those drones when there are no queens about?

The timing is due to the differences in the development time (from egg to eclosion) of drones and queens, together with the differences in the time it takes before they are sexually mature.

Drones take 50% longer to develop than queens – 24 days vs. 16 days. After emergence the queen take a few days (usually quoted as 5-6) to reach sexual maturity before she embarks on her mating flight(s).

In contrast, drones take from 6-16 days to reach sexual maturity.

Swarming tends to occur when charged queen cells in the hive are capped. These cells will produce new virgin queens about a week later and – weather permitting – these should go on mating flights after a further six days.

Therefore a colony that swarms in very early June will need sexually mature drones available 12-14 days later (say, mid-June) to mate with the newly emerged queen that will subsequently return to head the swarmed colony. These drones will have to have hatched from eggs laid in the first fortnight of May to ensure that they are sexually mature at the right time.

Decisions, decisions

How does the colony know to produce drones at the right time? Is it the workers or the queen who makes this decision?

I’ve recently answered a question on this topic for the Q&A pages in the BBKA Newsletter. In doing some follow-up reading I’ve discovered that (inevitably) it’s slightly more complicated than I thought … which was already pretty complicated 🙁

The workers build the comb and therefore determine the amount of drone vs. worker comb the brood nest contains.

I don’t think it’s known how the workers measure the amount of brood comb in the nest, but they clearly can. We do know that bees can count {{13}} and that they have some basic mathematical skills like addition and subtraction.

Perhaps these maths skills {{14}} include some sort of averaging, allowing them to sample empty cells, measure them and so work out the proportion that are drone or worker.

Whatever form this ‘counting’ takes, it requires direct contact of the bees with the comb. You cannot put a few frames of drone comb in the hive behind a mesh screen and stop the bees from building more drone comb. It’s not a volatile signal that permeates the hive.

However they achieve this, they are also influenced by the amount of capped drone brood already present in the colony. If there’s lots already then the building of additional drone comb is inhibited {{15}}.

Colonies therefore regulate drone production through a negative feedback process.

So … does the queen simply lay every cell she comes across, trusting the worker population has provided the correct proportions of drone and worker comb?

Not quite

Studies by Katie Wharton and colleagues {{16}} showed that the queen could also regulate drone production.

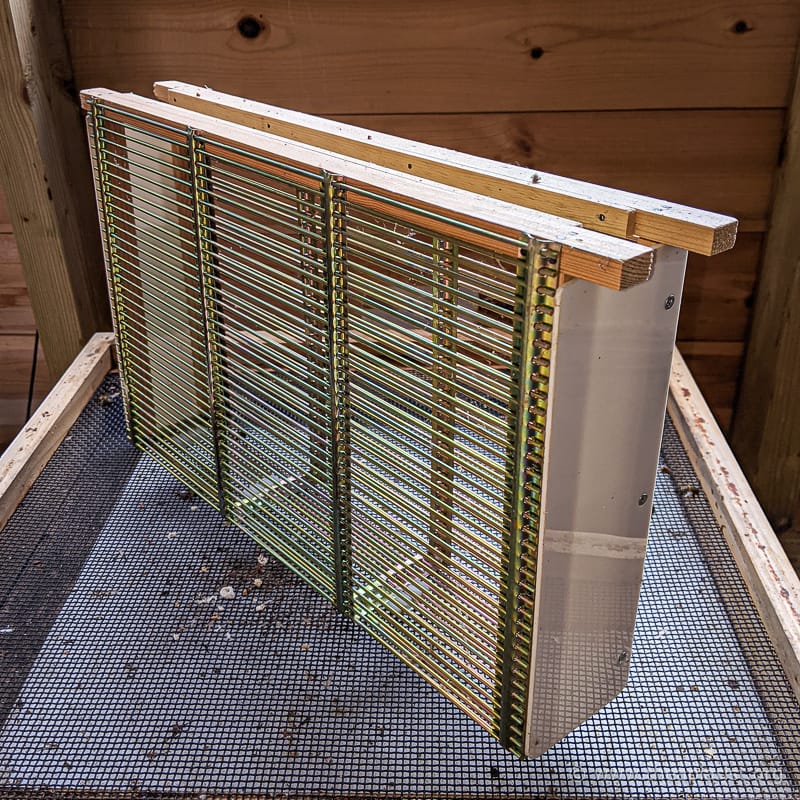

Wharton confined queens on 100% drone or worker comb in a frame-sized queen ‘cage’ for a few days.

She then replaced the comb in the cage with 50:50 mix of drone and worker comb and recorded the number of eggs laid in drone or worker cells over a 24 hour period (and then allowed the eggs to develop).

Queens that had only been able to lay worker brood for the first four days of confinement laid significantly more drone brood when given the opportunity.

The scientists showed reasonably convincingly that this was a ‘decision’ made by the queen, rather than influenced by the workers e.g. by preparing biased number of drone or worker cells for eggs to be laid in, by preferentially ‘blocking’ certain cell types with honey or by selectively cannibalising drone or worker eggs.

Interestingly, queens initially confined on worker comb laid significantly (~25%) more eggs on the 50:50 comb than those confined on drone comb. I’m not sure why this is {{17}}.

Wharton and colleagues conclude “these results suggest that the regulation of drone brood production at the colony level may emerge at least in part by a negative feedback process of drone egg production by the queen”.

So it seems likely that drone production in a colony reflects active decisions made by both workers and the queen.

Why has this spring been really hard for drones?

To be ready for swarming, colonies therefore need to start drone production quite early in the season – at least 4-5 weeks before any swarms are likely.

But with consistently poor weather, these drones are unlikely to be needed. Colonies will not have built up enough to be strong enough to swarm.

Producing drones is a high energy process – they are big bees and require a lot of carbohydrate and protein during development.

Under natural conditions {{18}} a colony puts as many resources into drone production over the season as it does into swarms.

Thomas Seeley has a nice explanation of this in The Lives of Bees – if you take the dry weight of primary swarms and casts produced by a colony it’s about the same as the dry weight of drones produced throughout the season.

Rather than waste energy in drone production the workers remove unwanted drone eggs and larvae. The queen lays them, but the workers prevent them being reared.

How do the workers decide the drones aren’t going to be needed?

Do workers have excellent long-range weather forecasting abilities?

Probably not {{19}}.

If the weather is poor the colony will be unable to build up properly because forage will be limited. As a consequence, the colony (and others in the area) would be unlikely to swarm and so drones would not be needed for queen mating.

Free and Williams (1975) demonstrated that forage availability was the factor that determined whether drones were reared and maintained in the colony.

Under conditions where forage was limited, drone eggs and larvae were rejected (cannibalised) and adult drones were ejected from the hive.

Beekeepers are familiar with drones being ejected from colonies in the autumn (again, a time when forage becomes limiting), but it also happens in Spring.

And at other times when nectar is in short supply …

Those of you currently enjoying a good nectar flow from the OSR should also look at colonies during the ‘June gap’. With a precipitous drop in nectar available in the environment once the OSR stops yielding, colonies can be forced to eject drones.

It’s tough being a drone … which may explain why one of my PhD students has the name @doomeddrone on Twitter 😉

{{1}}: Yes, you guessed it, with two sets of chromosomes. I prefixed haploid with usually because you can get diploid drones but these are cannibalised shortly after hatching.

{{2}}: But don’t count on it.

{{3}}: Which doesn’t mean to say that some of us old beekeepers aren’t … we’re just more used to waiting.

{{4}}: At least my smaller colonies, though conversations with other beekeepers suggests my experience is not unique.

{{5}}: If I knew more about it!

{{6}}: In which case the queen often has laid some it it up.

{{7}}: And there were virgin queens scampering around in these nucs when I checked at the beginning of this week … and I fear they’ll still be there in a fortnight :-(

{{8}}: These charged queen cells don’t really count as I “put them there”. I’d have been disappointed if they weren’t there.

{{9}}: I don’t like seeing them early in the season as that’s probably the result of a failed queen that is now only (or mainly) laying drone brood. Failed queens, including drone layers, accounted for 100% of my winter losses this year.

{{10}}: Because they’re going to die trying … or die achieving.

{{11}}: Along with gratefully accepting their lost swarms in my bait hives.

{{12}}: Page, R.E. Jr (1982) The seasonal occurrence of honey bee swarms in north-central California. American Bee Journal 121:266-272.

{{13}}: Though not very high … they have an understanding of the concept of zero and can count up to 4, as well as having an appreciation of “lots” or “more”.

{{14}}: Which already exceed mine.

{{15}}: Free JB & Williams IH. (1975). Factors determining the rearing and rejection of drones by the honeybee colony. Animal Behaviour 23:650–675.

{{16}}: Wharton et al., (2007) The honeybee queen influences the regulation of colony drone production. Behavioural Ecology 18:1092-1099.

{{17}}: And, seemingly, neither are the authors as they don’t comment on it …

{{18}}: By which I mean unmanaged ‘wild’ colonies … in managed colonies, for reasons described above, drone production is often significantly less than under normal conditions.

{{19}}: Wouldn’t it be great if they did? … No drones in the colony, the weather is going to be rubbish for the next month or Loads of drones, get the sunscreen out.

Join the discussion ...