Seasonal scheming

Synopsis : Midwinter is the time for planning and preparation for the beekeeping season ahead. In addition to thinking about the normal season’s events – swarming, mite control, honey etc. – now is the time to be more expansive. What arrangements need to be made for the longer term sustainability of your apiary and beekeeping? {{1}}

Introduction

Now is the winter of our discontent.

So said the young Richard {{2}} in a soliloquy celebrating the upturn in his fortunes.

For a beekeeper, this upturn might seem a little premature as it’s only 17 days since the winter solstice and there are currently less than 7 hours daylight.

The drowsy days of summer filled with the gentle buzzing of bees seem a lifetime away …

No cleansing flights today

… and it’s snowing in the apiary.

However, the days are slowly getting longer.

Actually, until the spring equinox, the daylength gets increasingly longer each day – by about a minute and a half on January 1st, to over 4 minutes a day by the end of the month and finally reaching a heady 4 minutes 48 seconds by the 20th of March {{3}}.

All of which means that, although not quite ‘around the corner’ the beekeeping season will be here pretty soon.

So it’s not so much Now is the winter of our discontent as Now is the winter and the best time to prepare for the season ahead and build frames.

I’ve previously posted about building frames, so this post is about planning, though frames might get a mention in passing.

Planning for the season ahead

I was going to title this post Cunning plans but I think most of the cunning plans that Baldrick dreamt up were pretty catastrophic. It seemed sensible to choose a different title.

I have an entire talk on the topic of planning for the season ahead and am giving this talk a couple of times in the next few weeks. To avoid stealing my own thunder {{4}} I’m not going to talk in general terms about preparing for the season.

Instead I am going to concentrate on the things I’ll be doing in addition to all of the usual activities like swarm prevention, the honey harvest and mite control.

At this time of the year we have the luxury to stare idly off into the middle distance while simultaneously dreaming about bees and polishing off the remains of the Christmas cake. Once the season starts we’ll either be too busy, or there won’t be enough time to make some of the preparations.

So what will I be doing this year that differs from last year, or the one before that?

Long distance beekeeping

I finally moved from the east coast to the western extremities of Scotland last February after a couple of years of spending increasing amounts of time here. I’ve still got bees on both sides of the country (including colonies for research in Fife) and travel to and fro as needed to manage the colonies.

And, frankly, the novelty is starting to wear off.

It can get a bit wearing spending the day working with the bees and then driving for 4-5 hours to get home {{5}}. Beekeeping can be hard work. There are lots of boxes to lift and it can get hot and tiring doing this for hours on a sweltering day in June.

Fortunately, this is Scotland, so the sweltering day bit doesn’t happen all that frequently 😉

However, the physical hard work does happen. I’ve previously calculated – using mental arithmatic on one of those long car journeys {{6}} – that my spring honey harvest might involve manhandling well over a ton of boxes over a couple of days. And that’s on top of the hive inspections.

Doing this ‘at a distance’ means everything tends to get squeezed into a 2-3 day trip every couple of weeks, or more frequently if I’m queen rearing as well.

OK, I’m not expecting much sympathy as you’ve probably also worked out by now how much honey all those supers contained 😉

Nevertheless, one priority this year is to reduce my hive count on the east coast, and increase it on the west coast.

Think of it as increasing the beekeeping : driving ratio.

Latitude and longitude

Don’t get me wrong, there are advantages of having apiaries 150 miles apart.

For a start, the timing of the key seasonal events – swarming and the nectar flows – are very different. Although there is only a fraction of a degree difference in latitude (perhaps equivalent to ~30 miles), the climatic differences are striking.

Warm and wet on the west coast, cold and dry on the east.

Or, more accurately as these things are all relative, warmer and wetter on the west coast, colder and drier on the east 😉

This, coupled with the geography, means that my bees in Fife are surrounded by intensively farmed land, whereas those on the west coast are in the howling wilderness.

And intensively farmed means oil seed rape (OSR). I don’t think there’s a single season I’ve been in Fife when OSR wasn’t available nearby. Even when the bees fail to collect a surplus the boost the colonies get from the bonanza of nectar and pollen is huge.

This means that the colonies are much bigger and stronger earlier in the season. They therefore make swarm preparations sooner and I can start queen rearing earlier.

All of which means that the 4-5 hours separation by car – less than 3° of longitude – is manifest as 3-4 weeks of difference in the beekeeping season.

And that means I don’t need the same equipment on both sides of the country at the same time.

Result 🙂

Local beekeeping

I think what these rambling comments really emphasise is the intensely local nature of beekeeping. The climate, geography and forage experienced by, or available to, colonies determines ‘what happens when’.

Specific advice on beekeeping can only meaningfully be applied if these factors are taken into account.

This is inevitably very confusing for beginners.

If a venerable sage pronounces on the discussion forums that ‘now is the right time’ for oxalic acid treatment, then it must be correct.

Yes?

Er, no.

The ‘right time’ reflects the combination of the mode of action of oxalic acid and the state of the colony. Oxalic acid is only effective against phoretic mites, so the colony should ideally be broodless. The timing of broodlessness will depend upon a host of factors, but will likely differ in different locations.

We’ve had a relatively mild winter (so far). My Fife colonies were broodless from late October through until sometime near mid/late November. A few I checked on the 7th of December had brood, and I expect they all did by Christmas (I’ve not checked since).

Had I not treated until the Christmas – New Year holiday my mite control would have been much less effective. Many mites would have escaped a drenching in oxalic acid as a consequence of being hunkered down in capped cells.

If you didn’t treat at all, or didn’t treat until the Christmas holidays, or didn’t treat when you know that the colony was broodless {{7}}, keep a close eye on the mite levels as the colonies expand this spring. If the winter remains mild the mites will have ample opportunity to reproduce to disturbingly high levels.

I seem to have drifted off topic …

Local bees

My Fife bees were all reared locally and the queens are open mated. They do well in Fife and possibly wouldn’t do quite as well on the west coast. They also have Varroa whereas my west coast apiary is in a Varroa-free region.

I therefore cannot simply reduce my east coast colony numbers by moving them.

Instead I’ll have to use a combination of splitting some to produce nucs for sale and uniting others to make strong colonies for the summer nectar flow. Hopefully this should leave me with a few very strong colonies which will be easier to manage and/or hand on when I finally leave altogether.

Like last year I’ll therefore be doing quite a bit of long distance queen rearing. I’ll raise the cells in Fife and then transfer them, once sealed, to my recently completed portable queen cell incubator.

This frees up the cell raising colony for a second round of grafted larvae. I’ll then keep the cells with me until the queens emerge, maintaining them with a tiny bit of honey and water every day. On my next visit to Fife I’ll then be able to transfer them to introduction cages and place them in mating nucs.

A trial run doing this worked well last year.

There are several advantages of doing things this way:

- The cell raising colony can be re-used about a week earlier than if I’d left the queens in it – either to emerge, or until they were ready for introduction as mature queen cells.

- Any dud cells (i.e. those that don’t emerge) are ditched instead of only being discovered when checking the mating nucs a week or two later {{8}}.

- I can use the queens to fit in with my own travel timetable – which has other things dictating it like pesky meetings – rather than vice versa.

But, of course, it also involves a bit more work in maintaining and caging the queens. In addition, in my experience virgin queen introduction is slightly more risky than adding mature cells to a queenless colony.

However, in my view, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages.

Expansion

I’ve successfully reared queens for several years.

I’m certainly not an expert, but I’m experienced {{9}} enough to expect it to work. I’m disappointed when graft acceptance is below about 75%, or when less than three quarters of my virgin queens fail to mate successfully.

Multiplied together (0.752) you get 0.56 … or ~50-60%. I therefore work out how many queens I need and graft twice the number of larvae and it usually works out about right.

So it is very frustrating when it doesn’t.

And it didn’t with my west coast queen rearing last season 🙁

Graft acceptance was low (though not catastrophic), but queen mating was very poor. I think this was due to a number of factors, some self-inflicted and some environmental:

- Colonies developed much more slowly meaning queen rearing needed to start later in the season.

- I had too few colonies, and certainly too few drones, to ensure enough ‘Summer lovin’ 🙂

- The weather. It can be a bit hit and miss getting sufficient ‘dry, calm, settled’ weather for queen mating this far north and west.

To expand my colony numbers on the west coast, and to generate surplus to help meet the demand for Varroa-free colonies in the area, I need to ‘up my game’ significantly.

Improved mating success {{10}}

There’s nothing I can do to change the weather though I have started to take an unhealthy interest in it.

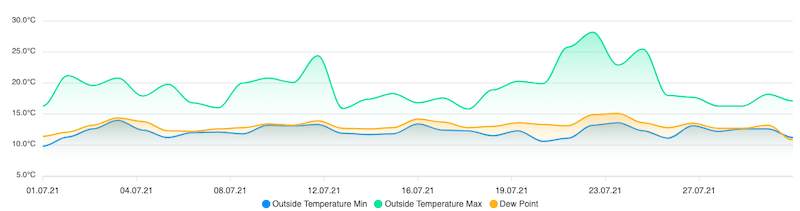

I’ve now got a personal weather station in the apiary which can generate graphs like that shown above (or for wind speed, sunlight, rainfall etc.). By retrospectively determining the local conditions that occurred during successful mating flights {{11}} I should be able to plan the timing of queen cell production a little better.

For example, if all that is needed is one half-decent day in an otherwise unsettled fortnight, it would make sense to produce a small number of mature cells over a long period. In contrast, if successful mating needs a longer period of settled weather – that might only occur once a season – then it might be better to have lots of queens (and mating nucs) ready for the time most likely to be suitable.

And the same considerations apply to drones.

Ardnamurchan is a very sparsely populated area … whether you’re counting people or bees. I strongly suspect that a major factor contributing to poor mating success was the relative sparsity of drones. To help compensate for this I am going to boost drone production in colonies by adding at least one full frame of drone foundation.

Regular readers will know I use a lot of foundationless frames. The colony preferentially draws these as worker or drone comb to fit their needs at the time. Consequently, many of my colonies often have more drone brood than a hive just filled with frames of purchased worker foundation.

However, this year I’m not even going to give them the option … I’ll drop a frame of drone foundation into the box so they just have to get on with it!

Finally, I can certainly improve my understanding of colony development on the west coast. Do I need to provide a syrup or pollen (pollen sub) boost early in the season to compensate for a local dearth of nectar and pollen? Are there other ways I could manage the colonies to ensure they are strong enough at the right time for cell raising?

So, part of my planning is to improve a number of things that contribute to successful queen rearing. Some of these will inevitably impact honey production, but that’s something I’m happy to sacrifice (in the short term at least).

A new apiary

For the first time I’ve got bees in the garden … or what masquerades as a garden in this part of the world. More accurately it’s just a patch of rough hillside with some mixed woodland and a really boggy bit (and an unhealthy amount of rhododendron).

For convenience I need to find an additional apiary this year. This avoids overloading an area with too many bees, and provides an additional site for queen mating or simply moving colonies temporarily during certain manipulations.

The usual quote is “less than 3 feet or more than 3 miles” when it comes to moving bees.

However, those rules aren’t absolute.

Mountains and expanses of water both significantly reduce the distances bees will fly (they prefer to go round them rather than over them).

And we have lots of both {{12}}.

I’ve scouted out a couple of locations already and have a couple more to check. My main apiary will remain in the garden but I’ll have an out apiary when needed.

Learn something new

The motto of perl, my favoured (and now very much out of fashion) computer programming language, is there’s more than one way to do it.

And exactly the same motto could be applied to beekeeping.

If you think about swarm control for example, you could use any one of at least a half dozen widely used methods, each of which has pros and cons.

Pagden, Demaree, nucleus, vertical splits, Taranov, etc. {{13}}. Any of them will do the job if properly applied. Some might be better than others, but they all get there in the end.

I’m a firm believer in learning to use one method really well before trying something new.

Learn its foibles, its strengths and weaknesses. Get good at it.

Then, and only then, try a different method. If you’re interested {{14}}.

It’s only by being confident and successful with one technique you’ll be able to judge whether a different one might actually be better.

Last year I used a Morris board for the first time. It’s like a Cloake board, but half the width. It didn’t work as well as the queen rearing method I usually use (a Ben Harden system). I think I know why and will be trying again this season.

I’m also going to try cell punching as an alternative to grafting. Cell punching involves cutting out a cell plug containing a larva of a suitable age and then presenting the entire plug to a queenless cell raiser.

I see this (if you’ll excuse the pun, which will become obvious in a second) as a sort of ‘future-proofing’.

You need good eyesight and a steady hand for grafting. My presbyopia is becoming more marked and I’d like to be able to rear queens reliably when I need glasses so thick they don’t fit under my veil 😉

There are more schemes being schemed (including something about frames), but they’ll have to wait until another time as I’ve already written too much …

Note

Coincidentally, on the day I made some notes for the last paragraph, Jeremy Burbidge at Northern Bee Books sent out a flyer announcing Roger Patterson’s new book Queen Rearing Made Easy: The Punched Cell Method. Roger is a strong advocate of this method and has written about it on Dave Cushman’s website. I’ve not read the book, but I have watched a few YouTube videos … what could possibly go wrong?

{{1}}: Regular readers will realise that this is an addition to a normal post. I wasn’t sure whether to call it a summary, abstract or precis (all of which suggests a little too much detail), so settled on synopsis. It might stay, it might be revised, or it might be quietly forgotten in a month.

{{2}}: In Shakespeare’s Richard III

{{3}}: At which point of course the difference in day length starts to decrease until the summer solstice. All these figures from timeanddate.com

{{4}}: And potentially reducing the audience by 100’s about 7.

{{5}}: I don’t think beefarmers have time to read this site, but any that do are currently thinking “What a wuss” or “Lightweight!”

{{6}}: All the normal warnings therefore apply … there wasn’t even an envelope involved, so you might want to treat this figure with caution.

{{7}}: Tut, tut.

{{8}}: Remember, I’m 150 miles away, I can’t have a quick peek a day or two after introducing the queen cell … at least not without a long car journey.

{{9}}: Or perhaps arrogant?

{{10}}: Fnarr, fnarr as they’d say in Viz

{{11}}: Or at least on the days of successful mating flights

{{12}}: Actually, ours are hills. The cutoff is usually considered to be 2000 feet (610 metres) and there’s no land higher than that within 10 miles or so.

{{13}}: OK, perhaps the latter isn’t ‘widely used’ … and there aren’t even six items in the list, but it’s all I could think of late at night.

{{14}}: You don’t have to.

Join the discussion ...