Window of opportunity

I’ve recently discussed problems faced by beekeepers trying to control high Varroa levels in colonies during the ‘body’ of the beekeeping season. Essentially the problems are two-fold:

- Many miticides need to be used for several weeks to target mites in capped cells.

- The soft or hard chemicals used for Varroa control are – with the exception of the formic acid in MAQS – incompatible with honey production.

This type of midseason mite management should not be needed if parasite levels are controlled in late summer and midwinter.

If it is needed it suggests that the treatment(s) failed or that mites are being acquired through robbing or drifting from other colonies in the neighbourhood (either your own, a nearby apiary or a feral colony).

Opportunity knocks

However, all is not lost. Most seasons offer at least one opportunity to intervene and control mite levels.

Knowing when and how to exploit it requires an appreciation of the development cycle of the bee.

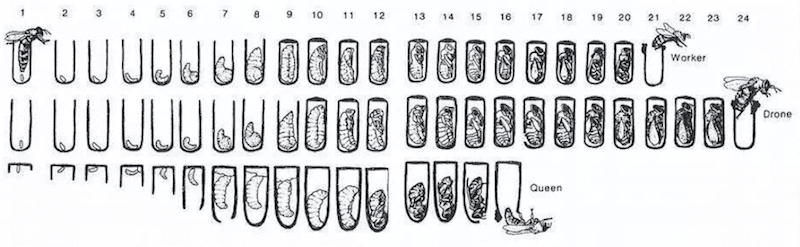

The important numbers are the 21 and 24 day development cycle of workers and drones respectively, the 16 day development cycle of the queen and the time it takes for eggs to hatch, grow as larvae and pupate in capped cells.

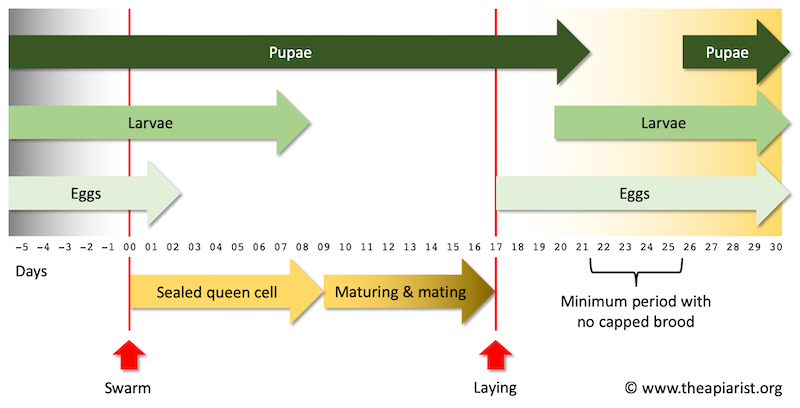

Not shown is the maturation period after emergence for the queen (5 to 6 days) before she goes on a mating flight, or the delay after returning before she starts laying (2-3 days) {{1}}.

Swarms

The easiest scenario to discuss is when the colony swarms.

Consider the swarm first. A prime swarm is broodless, contains a mated queen and ~35% of the mites that were present in the issuing colony. All the mites will be phoretic. Assuming there’s drawn comb available the queen will start laying soon after the swarm is hived (or conveniently moves into your bait hive).

Eight days later the first eggs will have hatched, the larvae grown and the brood will be capped.

At which point the majority of the mites will start to become inaccessible again.

However, during those 8 days it’s ‘open season’ for those phoretic mites.

It is sensible to quarantine swarms from an unknown source and treat for mites in the first 8 days if needed.

If the swarm is a cast with an unmated queen you’ve got a bit more time. The virgin queen needs to get out and mate, mature and start laying. This tends to happen in just a few days if the weather is accommodating, so don’t leave things too long.

The swarmed colony

Now consider what’s left in the colony that swarmed {{2}}. There will be sealed and unsealed brood and – notwithstanding the reduced egg laying by the queen as she’s slimmed down in preparation for swarming – there are also likely to be some eggs.

There will also be a sealed queen cell (and, in a strong colony, several sealed and unsealed queen cells).

Without intervention the queen(s) will start emerging about 9 days later. If you intervene, knocking down all the sealed cells and leaving just one good charged open cell {{3}}, it will be a couple more days before the queen emerges.

Weather permitting it will be a further 8 days before the newly mated queen starts laying. In reality, this is the absolute minimum and is rarely achieved in a full hive {{4}}.

Simultaneously, in the requeening hive, the open brood is maturing and being capped and the capped brood is emerging (releasing more mites).

About eight days after the swarm leaves all the worker brood in the hive will be capped.

Twenty one (or 24 in the case of drone brood) days after the last egg was laid by the queen all the brood will have emerged.

Consequently all the mites in the colony will be phoretic.

The window of opportunity

So, if you need to treat {{5}} the window of opportunity is between the last of the brood from the old queen emerging and the first of the larvae from the new queen being capped.

You can determine when this is likely to be based upon the known activities of the old and new queen during the swarming period.

The diagram above makes a number of assumptions. As presented, all minimise the duration of the minimum broodless period:

- The old queen continues laying until the day she swarms

- The colony swarms on the day the queen cell is sealed

- The beekeeper does not intervene to leave an open, charged cell of a known age

- The new queen takes the minimum amount of time to mature, go on a mating flight and start laying

It should be self-evident that more realistic timings applied to these will only increase the length of the minimum broodless period.

For example, the weather will have a significant impact. Swarming may be delayed due to adverse conditions. During this time the slimmed-down queen will probably lay very few eggs.

Similarly, only 8 days are shown for maturing, mating and starting to lay. Mating flights are very weather-dependent and this period could easily take a week longer (or more).

Splits and artificial swarms

If you practice swarm control using the nucleus method, vertical splits or the classic Pagden artificial swarm the same types of calculations apply.

These three methods all share two features:

- They involve the physical separation of the box with the old queen and the new developing queen

- The old queen is isolated with a very small amount of brood – either open brood or emerging brood

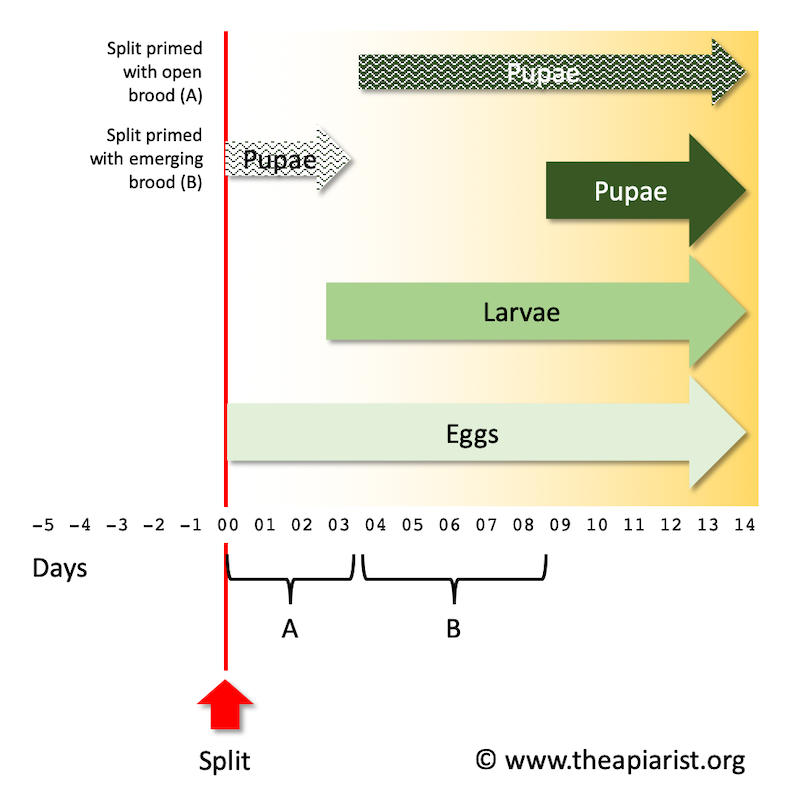

The queenright component of the split (whether nuc box or new brood box left on the old site) will follow the right hand part of the diagram above i.e. everything to the right of the vertical red line labelled laying. Here it is expanded a bit:

The queen should start laying almost immediately if drawn comb is provided meaning this new brood will be sealed in a further 8-9 days. The timing and duration of the minimum broodless period depends upon whether you prime the queenright split with a small amount of open or emerging brood.

- Open brood will be capped within about 6 days of the eggs hatching. If the frame contains nothing older than 3rd instar larvae (about mid-size) you will only have about 3 days before the cells are capped – indicated by bracketed region labelled (A) above, with capped pupae shown by the dark shaded arrow.

- Emerging brood offers a bit more flexibility. If all the brood emerges in the first 2-3 days after the split (shown with the pale shaded arrow) then the duration of the broodless period, shown in (B) above, lasts about 5 days.

Queenless colonies after splitting

The queenless part of the split will behave like the swarmed colony in the upper line diagram. All capped worker brood will have emerged 21 days after the split (drones after 24 days).

Capped brood arising from eggs laid by the new queen in this colony will depend upon the origin of the queen.

If the colony is left to rear its own queen then the timing will be similar to the upper line diagram plus the additional time required to create a capped queen cell (which rather depends upon the state of the colony when split).

However, if you add a mature queen cell a day off emergence you will reduce the time to the appearance of new capped brood by ~8 days. Consequently the colony will probably never go through a phase with no capped brood present. This is the same, but even more so, if you requeen the colony with a mated queen.

The miticide of choice

Of all the (rather limited range of) miticides available, an oxalic acid-containing treatment is the most appropriate. Oxalic acid (OA) is well-tolerated and, if used on a colony that lacks capped brood, over 90% effective. In addition, and critical for treatment in a narrow window of opportunity, only one treatment is required.

OA can be administered by trickling or sublimation. I’ve covered both methods in detail previously so won’t repeat what’s required, or the recipes, here.

Note that in many cases although the colony will have no capped brood it will not be broodless. For example, larvae from eggs laid by the new queen will be present but uncapped.

This is important because trickled oxalic acid-containing treatments are toxic to open brood. Under these conditions the treatment of choice would be sublimated oxalic acid.

Finally, note that if you are going to sublimate Api-Bioxal you’ll either have to spend ages cleaning the pan of the vaporiser, or line it with aluminium foil in advance.

The treatments outlined here are not intended for routine use. They should be used only if needed based upon mite counts or overt signs of DWV-mediated disease.

However, if you do need to treat make sure you do it when the treatment will be most effective.

{{1}}: These are really minimum periods … it can take a lot longer for the queen to get mated.

{{2}}: Of course, if it’s not your colony that swarmed you won’t have access to it. However, by discussing this here I can more easily deal with splits later.

{{3}}: The advantage of this is that you’re more in control of the timing of subsequent events. Remember to return 7 days later to knock back any additional cells started, by which time there will be no larvae young enough to start new cells from.

{{4}}: But interestingly isn’t unusual in a mini-nuc.

{{5}}: Not otherwise … I’m not advocating treatment unless it is necessary because of overt signs of DWV or unseasonably high mite counts.

Join the discussion ...