Hard graft

Regular readers will have seen this image before …

… as I used it (with the same legend) towards the end of the post last week.

I spoke too soon 🙁

The temperature on the 17th and 18th briefly reached 17.5°C … which was enough.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Good morning America Glenrothes

I’m fortunate to live in a stunningly beautiful and remote part of the country. I open the blinds in the morning to panoramic views of the Morvern hills across a narrow sea loch. There are no houses in direct sight and – even when it’s damp {{1}} – it’s an idyllic scene.

But although I live here, most of my bees still live in Fife, so I have a commute to look after them and stay in convenient {{2}} hotels.

Opening the curtains on these trips provides a somewhat less salubrious view.

But at least I don’t have to cook my own breakfast, which is but a short walk away 🙂

As you can see from the photo above, it’s been raining overnight.

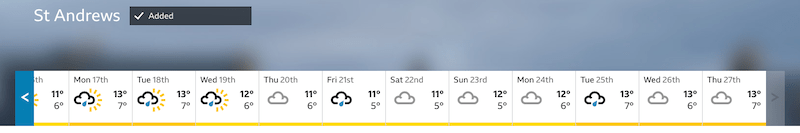

To make these trips economically rational {{3}} it’s necessary to book them several weeks in advance.

Despite the use of supercomputers, the BBC’s medium to long-range weather forecasts seem little more than guesswork. It’s worth remembering that a weather forecast competition over several weeks was won by a team that predicted ‘tomorrow will be like today’ for the duration of the event {{4}}.

And for beekeeping, there’s a significant difference between 12°C, light drizzle with strong winds and 13°C, intermittent sunshine and gentle breezes.

The latter makes opening hives a relatively straightforward proposition … careful and quick, but the bees will cope just fine.

In contrast, the former makes everything rather hard work.

And these are exactly the conditions that greeted me when I did my first round of grafting on the 10th of May.

The weather is probably the major problem of long distance beekeeping. You have to be prepared for anything.

Queenright cell raising – the Ben Harden system

I’ve discussed grafting and using the Ben Harden queenright cell raising system extensively before.

My Ben Harden setup was in the bee shed.

As it turned out, this was a (disappointingly rare) stroke of genius.

A strong, double brood colony had been modified be the replacement of 7 frames in the upper box by two ‘fat dummies‘. These have the effect of concentrating the bees in the gap between them.

In this space were two frames containing pollen, one frame of young larvae {{5}} and the cell bar frame, into which I would be grafting larvae.

This box sits on top of a queen excluder, below which was a single brood box (containing the queen) literally overflowing with bees {{6}}. Positively bulging at the seams.

Since I didn’t have frames with sufficient pollen in them I’d also supplemented the colony with pollen substitute (a pollen pattie) which they were happily devouring.

The hive also had a couple of half-full supers. These contained lots of bees but rather disappointing amounts of nectar.

The queen providing the larvae was in a nuc box in the same apiary. I’d been feeding this colony syrup and pollen to ensure the young larvae were well fed {{7}}.

Grafting

The day for grafting dawned cool, grey and drizzly.

Great 🙁

I ended up doing the grafting in the passenger seat of the car, wearing a headtorch. I kept the larvae warm and humid using a damp piece of kitchen paper draped over those I’d already transferred from the comb to the plastic cups in the cell bar frame.

After gently inserting the cell bar frame into the space in the centre of the Ben Harden setup and filling the feeder in the fat dummy with syrup, I added a clearer board and then replaced the two supers.

The intention was to empty the supers into the cell rearing box, guaranteeing a huge number of bees would be there to help raise the queens.

After another evening of junk food and a disappointingly similar breakfast I checked the grafts the next day for ‘acceptance’.

You do this by – ever so gently – lifting the cell bar frame from the centre of the Ben Harden setup and looking for a 5-6mm collar of fresh wax built around the lower lip of the Nicot cup into which the larvae have been grafted.

Amazingly, considering the dodgy conditions and the fact that this was my first attempt at grafting for a couple of years, all the larvae appeared to have been accepted {{8}}. I didn’t brush any of the bees off and I certainly didn’t prod about in the densely packed bees on the frame … but things looked good.

So I closed the hive up and went off to inspect some other colonies in the rain before driving back to the west coast.

Coffee mishaps and colony inspections

I returned to the east coast about 8-9 days later to add the queen cells to nucleus colonies.

The ~150 mile journey didn’t go well. In mid-slurp the lid came off my mug, depositing a lap-full of lukewarm coffee over me.

Never mind. The route I take goes through some ‘modesty-ensuring’ remote countryside. It was a five minute task to leave the trousers drying over the boxes of frames in the back of the car.

Since I had no spares I donned my beesuit and continued on the journey.

The weather improved as I drove east. I checked an apiary in mid-Fife where all was well and finally arrived at my main apiary in mid-afternoon.

It was a lovely day 🙂

So lovely one of the colonies had swarmed 🙁

There were actually two small swarms hanging about a metre apart in the willow trees I’d planted around the apiary {{9}}.

I didn’t really have time to think about the swarm … we needed a few hundred early stage drone pupae for work so went through the colonies to find these first.

These were quick ‘n’ dirty inspections … I checked every frame, but not every cell or every nook and crannie …

- brood in all stages?

- eggs?

- stores?

- any charged queen cells?

- temper, behaviour, stable on the comb?

- anything weird or strange? {{10}}

- next please …

I didn’t check the hive I’d set up for queen rearing, or any of the nucs on site that contained virgin queens. However, all of the other colonies were queenright as determined by the presence of eggs and the absence of (obvious {{11}} ) queen cells.

Drone brood was either present in relative abundance – in the strong colonies – or notable by its absence. This should not be unexpected to those of you who read the post on drones last week.

To the tune of ‘Ten green bottles’ … all together now, ‘Ten capped queen cells hanging on a frame …’

And I still had 10 queen cells in the cell raising colony, all now capped and ready to use the following day 🙂

And the swarm?

The swarm (either of them if there were actually two) wasn’t really big enough to be a prime swarm. These contain a mated queen and ~75% of the workforce from the hive. None of the hives appeared short of bees and I’d found no (obvious {{12}} ) charged queen cells.

However, I’d not checked the queen rearing colony – packed full of bees and fed copious amounts of syrup – and one of the colonies on the site was very bad tempered {{13}}.

Poor temper is often a sign of a queenless colony.

Anyway, back to the swarm.

I dropped each clump of bees into a separate nuc box containing a frame of drawn comb and a couple of additional frames. I left these in the shade until late afternoon when I’d finished with the other colonies.

By late afternoon most of the swarm bees from one of the nuc boxes had abandoned it and joined the other nuc box. It was pretty clear that there was only one ‘swarm’ and that it had got separated when settling at the bivouac.

The bees were leaving the queenless box and joining the queenright one.

I checked the willow where the swarm was found.

There were small amounts of wax deposited on the leaves and stem of the willow. I suspect that the swarm may therefore have been there overnight {{14}} but can’t be sure.

I ended the afternoon by putting the hived swarm on a hive stand in the apiary.

Before leaving I checked the bad tempered colony (which I was intending to split into nucs the following day).

During my fumblings I managed to get a few bees into my beesuit pocket {{15}}.

The one with the hole in it from my razor-sharp hive tool.

That opened onto my leg.

Which was unprotected by trousers due to my fumblings with the coffee 9 hours earlier 🙁

Ouch 🙁

Getting nuked

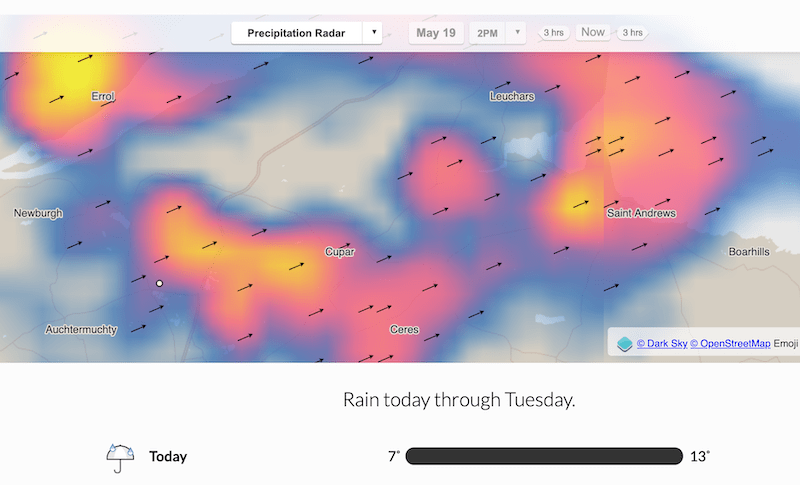

The weather the following day started bright but rapidly degenerated.

By the time I’d got the nuc boxes prepared – feeders, frames, stores, dummy boards, entrance blocks, labels, straps – it was 11°C and there was rain quickly approaching from the west.

The first four nucs were prepared from the ‘bad tempered’ hive (#6). I decided it was wise to get this over and done with before the heaven’s opened.

Despite going through the box twice I failed to find a queen. Perhaps she went with the smallest prime swarm ever?

I divided the frames (by brood and bees, not number of frames) into four approximately equal nucs and added a queen cell to each.

Each queen cell was removed from the cell bar frame, the adhering bees gently brushed off (with a handful of weeds) and pressed into a thumb-sized indentation in the comb, just underneath the top bar of the frame.

I then carefully pushed the frames together (avoiding crushing the cell) and closed the nuc box up.

As I opened the next hive to be split the rain started …

… and the wind lessened, meaning the rain stayed.

And it rained for most of the afternoon.

Rain did not stop play

In the words of the late Magnus Magnusson “I’ve started, so I’ll finish”.

And it was miserable.

For the second time in two days I was soaked.

As those of you who have hunched over open hives in the rain will know, it’s your back, shoulders and hood that catch the worst of it.

This time my trousers stayed mostly dry …

The high point of the afternoon (and, let’s face it, the bar was pretty low) was the realisation that housing the cell raiser in the bee shed was an inspired choice.

When adding queen cells to nucs you either have to detach them in advance from the cell bar frame and keep them warm somewhere convenient, or collect them in turn.

I had nowhere to keep them warm, so was returning to the Ben Harden setup to retrieve them one at a time. Since it was warm and dry in the shed I could leave the frame balanced (as shown above) still festooned with bees and fetch each cell as needed.

Had they been outside I would have had to stop.

It was difficult enough making up the nucs in the rain, one hand holding a frame, the other lifting the roofs on and off.

It would have been impossible to juggle the cell raiser and cell bar frame as well.

But I eventually finished and moved half a dozen of the nucs to another apiary {{16}}. I put the Varroa trays underneath {{17}}, filled the feeders with syrup and opened the entrances a half inch or so to allow the bees to fly.

And then I returned to the main apiary to tidy up.

And the swarm?

I still don’t know where the swarm came from {{18}}.

I checked it between downpours.

Despite opening the box very gently, with almost no smoke, the bees ‘balled’ the queen and killed her. I found her in the middle of a golf ball-sized clump of bees on the floor.

After dislodging some of the bees with my fingers I found her, laying on her side, as dead as a dodo. You can just see her in the photo above., slightly below the middle of the image by the edge of the mesh.

Why did they do this?

I’ve inspected dozens of swarms the day after hiving them and don’t ever remember having this happen before.

Perhaps it was the poor weather? Maybe my ‘very gently’ wasn’t gentle enough?

The queen was unmarked and (obviously) unclipped.

To me, she looked like a virgin queen, rather than a slimmed down mated queen {{19}}.

There were two nucs in the apiary containing virgin queens. I didn’t inspect either, but a quick peek through the plastic crownboard showed both still appeared to contain bees. The size of the swarm, although small (as swarms go) looked much larger than the size of these nucs.

I’ll check again next week …

I added a queen cell to the swarm and set off for home.

It’s a beautiful commute, across Rannoch and through Glencoe, chasing the setting sun.

And my trousers were finally dry 😉

Note

I’ve already grossly exceeded my self-imposed word count this week. This is not meant as a practical guide to queen rearing {{20}}. For those interested in queen rearing – the most fun you can have with a beesuit on {{21}} – there are lots of articles here with the nitty gritty practicalities. Try these for starters … queen rearing, an introduction to the Ben Harden system, setup and cell raising.

{{1}}: Which it can be … we get up to 2 metres of rain a year.

{{2}}: i.e. cheap.

{{3}}: i.e. cheap.

{{4}}: Though I can’t now find the link …

{{5}}: To encourage nurse bees up from the lower box.

{{6}}: When making this box up I’d removed frames of stores and underused frames, keeping all the frames of brood – the bottom box was packed with these.

{{7}}: In a more normal season this might not be necessary … the OSR should be yielding well by mid-May and that should be sufficient. However, low temperatures have retarded everything by 2-3 weeks this year.

{{8}}: I graft in batches of 10 … I don’t need more queens than that at once and I don’t want to overstretch the bees in challenging conditions.

{{9}}: These were planted in early 2019 and are now 2-3 metres tall.

{{10}}: I’ll return to this in a week or two, as there was one oddity I don’t have time to discuss now.

{{11}}: I didn’t shake the bees off the frames and they’re quite cunning about squirrelling them away in odd corners …

{{12}}: That needs qualifying again. I’d found a swarm near an apairy full of hives – anyone familiar with Occam’s razor would, probably correctly, assume it was one of those hives that had swarmed.

{{13}}: My first three stings of the season (and actually the first in 15 months I think) all to my nitrile-gloved right hand. These gloves allow the sting to be felt, but prevent it becoming embedded. More importantly, they allow you to feel – or pick up – individual bees. A near-perfect combination of protection and sensitivity.

{{14}}: The day before had also been a balmy 17°C.

{{15}}: Don’t ask … it had been a very long day.

{{16}}: Further east, where it had now stopped raining.

{{17}}: I like solid floors on hives from which virgin queens are going to mate … I want to avoid the returning queen missing the entrance and ending up underneath the open mesh floor. So close and yet so far.

{{18}}: It didn’t come from the cell raiser. I checked this late in the afternoon. The queen was present and laying well.

{{19}}: She looked reasonably crisp and fresh, despite being very dead.

{{20}}: Though it could be considered as a guide on what not to do.

{{21}}: Trousers are optional.

Join the discussion ...