The future is almost here

Synopsis: Brace yourself, 2024 is almost here. Time to start preparing for the ‘unknown knowns’ and perhaps making plans to try something new. Happy New Year!

Introduction

Incrementally, but imperceptibly, the days are lengthening.

The winter solstice (from the Latin sol = ‘sun’ and sistere = ‘to stand still’) was at 3:28 am on the 22nd. A debilitating cocktail of Covid, Lemsip, honey and Glenmorangie conspired to ensure I missed it, though I’m not sure it would have been particularly memorable as it was very wet and windy.

And the middle of the night.

Now, a full week later, the day length – at my latitude of ~56°N – is almost 4 minutes longer.

To be honest, I’ve not noticed.

The increases, day upon day, are so small that it will be weeks before they accumulate sufficiently to make a meaningful difference to what I can achieve on those days dry enough to work outside.

However, by the end of next month these increases will be galloping along at over 4 minutes per day, and will continue until the spring equinox in the third week of March, when the rate starts to slow.

Even though the current increases in day length are of little immediate benefit, they are a welcome reminder that the beekeeping season is getting nearer.

With no practical beekeeping to be done for at least 2-3 months we’ve got no excuse not to plan for the season ahead and start to make the necessary preparations.

Of course, that ‘2-3 months’ very much depends upon your latitude.

The beekeeping season started in early March in some years when I lived in the Midlands, but it could be early May in a cold Spring here in Scotland {{1}}.

The unknown knowns

Whether it’s a few short weeks – or a few long months – until the season starts, the events you must prepare for in the coming year are pretty much the same whatever your latitude.

These are the knowns.

Whether you live on the Channel Islands or Shetland Islands the bees still have to build up in spring, expand sufficiently to swarm (or at least think about it) and collect enough stores to get through next winter.

But, overlaid on these events in the lifecycle of the colony are the additional things we impose on our bees; splits, queen rearing, honey harvests and Varroa management.

More knowns, at least if you’ve kept bees for more than a year.

Obviously, as the latitude increases these are all shoehorned into an ever shorter season.

Those of us living in the north probably have less time during the season, though this is compensated by having more time before the season starts.

This explains why I’m always so well-prepared for the season when it does eventually start {{2}}.

So what is it about these knowns that are unknown?

Every season is different. You know what to expect, but you don’t quite know when to expect it.

Yes, queen rearing probably overlaps with the tail end of the OSR nectar flow, but that can vary by 2-3 weeks depending upon the weather (or the particular strain planted by the farmer). Perhaps more in a particularly warm or cold spring.

Furthermore, the events can get ‘disconnected’. The OSR will flower, but it can still be far too cold – and the colonies insufficiently strong – to think about queen rearing.

You have to use a combination of experience, good judgement, local advice, detailed observation … and a generous sprinkling of guesswork.

And it’s not just latitude …

My east and west coast apiaries are almost at the same latitude. Those on the west coast are less than 25 miles further north than my apiaries in Fife.

However, the seasons are fundamentally different.

Almost nothing happens on the west coast until mid/late May. Of course the bees are out and about, but colony build-up is slow and steady. I usually do my first round of grafting in the first week or so of June. Around me there’s no significant nectar flow until the heather in mid-August. There’s all sorts before then, but none produces an excess … and the lime has never yielded anything significant.

In contrast, with a warm spring, colonies in Fife might be swarming by late April and I’ll start queen rearing as soon as I can.

Central Fife has lots of rich arable farmland and so there is usually quite a bit of OSR about, meaning the spring honey must be harvested in early June. ‘Must be’ because any significant delay and it crystallises in the frames, making extraction a nightmare.

It is fortunate that the beekeeping season on the east and west coasts are not in perfect lockstep. With my infamous organisational skills – and inability to be in two places at the same time – it would be chaotic.

Preparing for the season ahead

What you need to do before the season starts very much depends upon:

- what you ran out of last season

- your plans for this season

- how well organised you are

It’s rare that I don’t run out of frames during the season. In fact, irrespective of the number I prepare in advance, I often find myself nailing a couple of dozen extras up on June evenings. It’s almost as if the presence of ‘spare’ frames in the shed somehow encourages colonies to make swarm preparations, or subconsciously influences my grafting success rate, meaning I’m making up more nucs than planned.

Frame building will start once it’s warm enough to work in the shed; experience shows that it hurts like hell if you inadvertently hit a chilled fingertip with a wayward hammer.

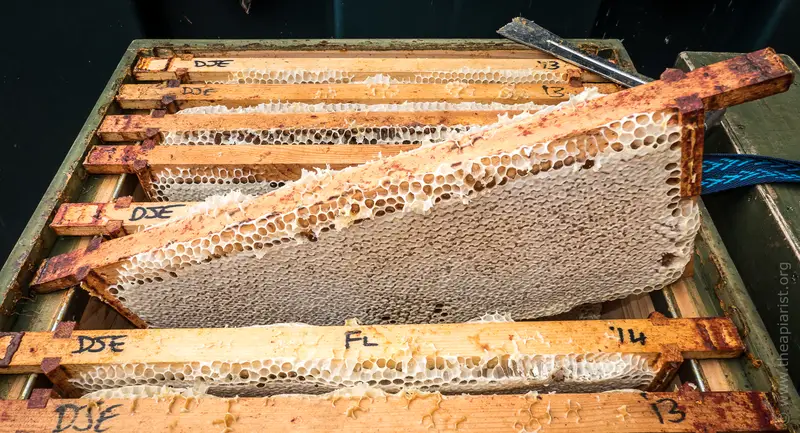

This year I need more frames that usual. I have been tardy rotating old brood frames out of some colonies and so am planning to do some shook swarms (or perhaps Bailey comb changes) to get the bees onto fresh comb.

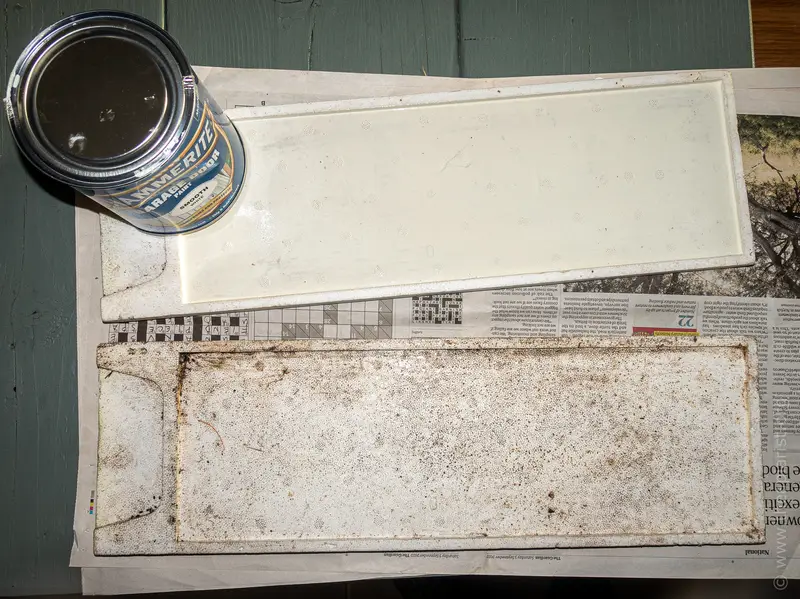

Most other things are just about ready. I’ve still got a few boxes to clean and some nucs to paint.

I also discovered a tin of white gloss paint (actually off-white it’s so old!) and am using it to paint the polystyrene Varroa trays that are supplied with Thorne’s Everynucs and the Abelo poly floors. These trays quickly discolour if used unpainted, making it nearly impossible to spot any dropped mites.

Painting them makes them much easier to use. Inevitably, most of mine are already discoloured, so they need a thorough scrub before painting … and then several coats.

For once I’m not building any new kit this winter … I’ve got more than enough already.

Queen rearing and honey production

These are the two fixtures in my beekeeping season. Fixtures as in I always do them, though the timing may vary a bit.

As I discovered in 2023, honey production can be a complete washout if the summer is particularly poor. Since there’s nothing I can do to influence the weather, and it’s rarely as poor as it was in 2023, I’ll just cross my fingers.

Not so much a fixture as a ‘hoped for fixture’.

Over the years I reckon about one year in four is much better and one much worse than average. This seems to apply to each of the two honey harvests {{3}} a season. Fortunately it’s rare that both spring and summer are poor in the same year.

Not only can I not influence the weather, but I also have no control over the forage available. I don’t move my bees about. All I can hope for is good enough weather so that the nectar flows and the bees can fly to collect it.

In terms of preparation for honey production, it mostly happens once the season starts; uniting any weak colonies, or giving stimulative thin syrup feeds or protein sub patties to boost others etc.

If the bees are ready and the weather plays nice then everything should be OK.

In contrast to honey production, I always feel as though I have a bit more control when it comes to queen rearing.

Delusional perhaps, but that’s the way it is.

Little and often

There is nothing that beats a good summer day in Scotland.

However, I acknowledge that the summers here are a bit less dependable than those further south.

It therefore makes sense to use queen rearing methods that do not commit significant resources {{4}} or that produce large numbers of queen cells all at once.

Far better to produce a trickle of queens over an extended period so you’ve not got ‘all your eggs in one basket’.

Remember, a newly emerged queen has a finite period (about 28 days from emergence) before she is too old to successfully mate. Two to three weeks of bad weather can be terminal. The same lousy conditions can also make for lots of extra work managing mini-nucs, and it’s possible that both the virgin and the workers in the mini-nucs are effectively ‘wasted’.

For this reason I try and produce a few queen cells every fortnight or so. If the weather is poor I (try and) find the old, unmated, virgin and replace her with a fresh cell …

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try and try again!

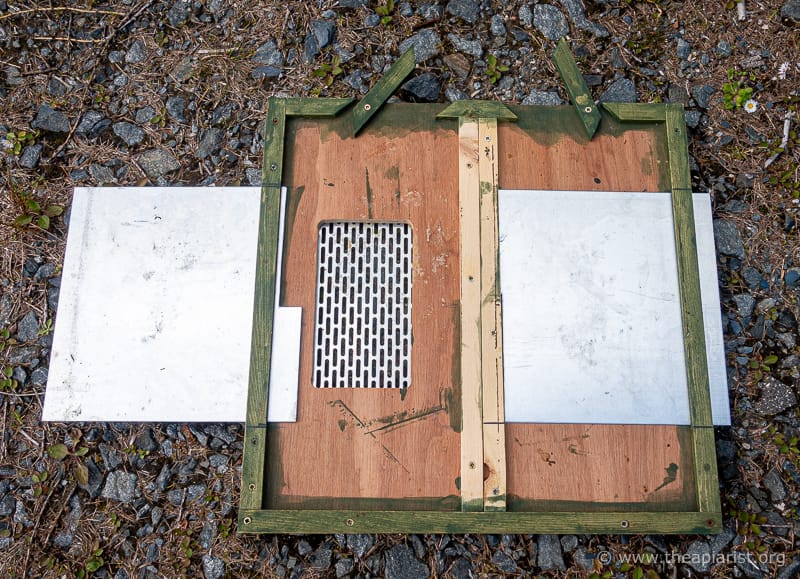

Morris boards and the Ben Harden system

For the last couple of years I’ve been dabbling with a Morris board for queen rearing on the west coast. It is functionally equivalent to a Cloake board except the bees are concentrated into only half a brood box above the excluder.

For my native black bees – which typically never expand much beyond a single brood box – this is useful, though perhaps not very different from my favoured Ben Harden system.

Using a Morris (or Cloake) board the cells are started in a hive that is temporarily queenless, whereas the Ben Harden setup is queenright throughout.

Starting cells is probably slightly more efficient using the Morris board, but I can’t say I’ve noticed any real differences in the quality of the resulting queens.

One disadvantage of the Morris board is that you have to redirect the bees from a lower hive entrance to an upper one, and from an entrance at the back of the hive to one at the front. In bad weather this is a recipe for confused and chilled bees … in which case the Ben Harden system may be a better choice.

The plan for next year is – as usual – to prepare enough queens for my own requeening, plus a few extras with any spares being used to make up nucs for overwintering.

These overwintered nucs are great to have in the spring to:

- replace any overwinter losses (though thankfully my recent losses are negligible)

- unite with underperforming production colonies that need boosting in spring, perhaps because the queen is ageing

- sell … overwintered nucs have ‘proved themselves’ and, since they’re available before queen rearing starts, they go for a premium price

Try something new

I’ve repeatedly suggested that success in beekeeping involves learning a method sufficiently well that you can absolutely rely upon it.

Don’t chop and change until you master the method.

For me, the nucleus method of swarm control and queenright queen rearing are my “old faithfull’s”.

But that doesn’t mean they’re the best way of preventing swarming, or rearing queens. In fact, there probably isn’t a best way; it depends upon what you want to achieve, the equipment available, the time involved, the phase of the moon.

Well, perhaps not the last of those.

So, having mastered methods that work, it’s interesting to try something new.

Although I’m tempted to have a go at the Taranov method of swarm control (which I briefly described a few weeks ago), the reality is that it requires quite a bit of preparation and some new equipment. I’m only likely to get round to it if I’m a lot better organised than I’ve been in previous seasons!

However, when it comes to queen rearing I’m already planning to have another (third?) go at cell punching. This involves cutting out entire cells from the comb containing suitably aged larvae and mounting them vertically on a cell bar frame (in contrast to just grafting the larva into a Nicot plastic cups). My first two attempts were, at best, underwhelming … another case of “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try and try again.”

I’m also going to have another go using the Hopkins method, described last June.

Both these methods avoid grafting … I’m making plans for the years ahead when my eyesight is so bad I can’t see the larvae.

The digital future

I set up The Apiarist website a decade ago in 2013.

It started as place to post my rambling thoughts on DIY for beekeepers which I’d written for my then association’s monthly newsletter.

In 2013 this site had 26 visitors.

I was chuffed. That probably doubled the readership of my newsletter articles.

Unlike a paper newsletter (which might, unread, be used to line the cat’s litter tray), you can ‘count’ the number of times a webpage is accessed. Although that’s not the same as knowing the post was actually read, it is a little bit more tangible … and therefore reassuring.

For about 5 years the website was rather chaotically updated; frequent though not regular posts, no clear house style.

Actually, little style at all.

Nevertheless, visitors – reassuringly amazingly – did appear to read some of the stuff that was written. Quite a few people. Comments per post increased. I ‘met’ (virtually or in person) some interesting people. Some even said some flattering things about the writing. Speaking invitations increased at associations and beekeeping conventions.

Page views increased … and carried on increasing.

The big time

In 2019 my goal was to reach a quarter of a million page views … from humans, not robots, though distinguishing between the two can be tricky (both online and elsewhere).

After all, if I was going to hammer out a post every week, using time I could just as well spend in the pub, or watching “I’m a celebrity”, or playing golf, I wanted the damned thing to be read.

I missed that target, though not by much.

In the last four years I’ve written more, I’ve posted regular as clockwork and readership has increased significantly. Typical page views per day in midwinter exceed one thousand with two to three times that number during the height of the beekeeping season.

Problems

The reading around a topic and the writing are enjoyable. I’ve had fun.

Undoubtedly the associated thinking has helped my beekeeping and I hope it has also helped you and those who also attend my talks.

But, as I indicated last week, the site attracts some unwanted attention; hackers attempting to control the site, thinly veiled ‘adverts’ masquerading as comments, and visitors – human or automated digital ‘bots’ – intent on stealing the content.

Hundreds or thousands per day.

Some are relatively innocuous; a hard-pressed association secretary searching for something for the monthly newsletter, a little CTRL-A, CTRL-C, CTRL-V action and voila, sorted.

Some are careful to attribute credit, a few go out of their way to disguise the origin.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but this site is read widely enough now that I’m sometimes forwarded the article … Oops!

If you are a hard-pressed association secretary tempted to do this, please write to me and ask in advance … requests to duplicate occasional articles, or for images, are rarely refused as long as credit is properly attributed. I only ask for a PDF copy for my records.

The rise and rise of ChatGPT

Much more concerning is ChatGPT.

ChatGPT is one of a slew of similar software applications that are trained on large language models (LLM). Essentially this means that they scour the web for content, catalogue topics and word associations, and then can produce ‘novel’ output when asked for it.

For example, ‘describe a queen cell in the style of a limerick’ :

In the hive, a cell fit for a queen,

A royal abode, rarely seen.

With waxen grace,

In a regal space,

A monarch-to-be, in yellow and sheen.

A trivial example, but there are entire blog pages on beekeeping ‘written’ by ChatGPT. Some are on sites selling beekeeping equipment and most are ‘commercial’ in one way or another {{5}}.

None of the content on The Apiarist is generated by ChatGPT {{6}} … but you can easily find them elsewhere if you search.

Look for superficial coverage of a topic, subtle non-sequiturs, repetition, cursory introductions with – typically – little personal perspective or strong opinions.

They’re obvious at the moment, but they will improve as they are further ‘educated’ by scalping the web for content to incorporate into their LLM.

And that ‘content’ potentially includes all the posts that I’ve written for The Apiarist.

That’s a gloomy thought for those of us trying to write novel and engaging content.

As the content ‘improves’ i.e. fewer errors and better punctuation, though probably no less vapid, you’ll see yet more of it. In time this ChatGPT-generated content will be incorporated into LLM’s.

It will feed itself.

Original writing will get increasingly rare and should be increasingly valued. But, as soon as it’s produced, there’s a danger it will be scalped, mushed-up and regurgitated by ChatGPT.

New Year, new start

I already ban ChatGPT bots from this site, but I can only block those that declare the purpose of their visit.

Most do not.

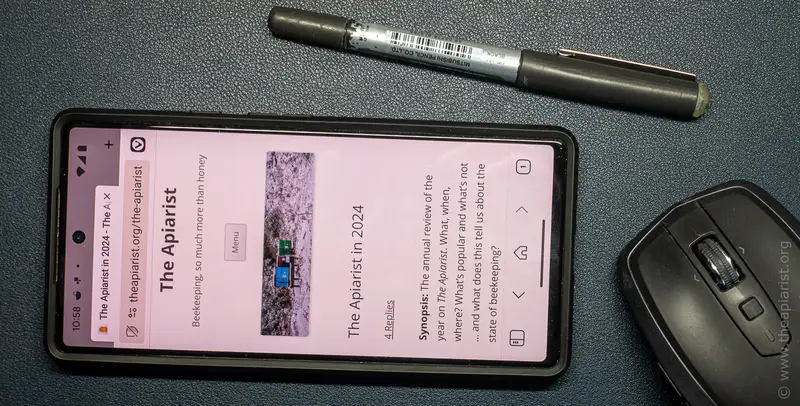

At some point in January I’m moving the site to a new, managed {{7}} software platform.

All current subscribers – those of you who are signed up to receive a ‘new post’ announcement – will be transferred though it is likely you will need to re-verify you want to continue to receive emails from The Apiarist website.

New posts will also appear as an email ‘newsletter’ – you’ll be able to read the content without visiting the website. The majority of readers use a phone/tablet rather than a computer. I compose the post on two large monitors, but you read it on a handheld device.

The new software will allow me to improve the layout and the graphics. It will also provide some future-proofing for article types I have planned but which the current software platform does not support. Some content will only be accessible to those registered to receive email notifications of new posts (i.e. not ChatGPT).

The comment system will change and should be much improved. The categorisation and tagging of posts – ignored by most readers – will be rationalised and made more useful.

There will undoubtedly be some teething problems. There are ~550 posts totalling ~1,000,000 words and containing ~900 Mb of graphics … inevitably there will be some incompatibilities somewhere.

Bear with me!

Happy New Year

I’m writing this in the last few days of the year. 2024 doesn’t look too appealing at the moment; more political upheaval, conflict, environmental damage and climate extremes.

More of the same and then some.

I hope your beekeeping provides a rewarding focus of peace and happiness whatever the year produces.

May your supers be heavy, your queens fecund, your bees well-tempered and your swarms … someone else’s

Happy New Year

Note

It appears that the future was already here last week … I’ve only just realised that the post on the 22nd was titled The Apiarist in 2024 when it was actually a retrospective review of 2023. D’oh! I blame it on Covid. I was totally wiped out. I’ve now fixed that and all the incorrect dates within the body of the post (with thanks Archie and Axel 😉 ).

{{1}}: Of course, none of the above applies to beekeepers in the southern hemisphere (where your days are now imperceptibly shortening).

{{2}}: Ahem!

{{3}}: Or perhaps now three if you include the heather on the west coast.

{{4}}: e.g. triple-decker cell raising colonies.

{{5}}: Of course, some are not ChatGPT-generated, they’re just rubbish.

{{6}}: Other than when clearly stated, like that limerick.

{{7}}: i.e. I’m paying someone else to deal with all the ‘backend’ security, upgrades etc. to allow me to concentrate on the writing.

Join the discussion ...