Winter projects

The good late summer September weather {{1}} has been replaced with the first of the equinoctial gales. Actually, more of a 30-40 mph stiff breeze with an inch or two of rain than a real gale. Nevertheless, wet and windy enough to preclude any outdoor jobs, and instead make my thoughts turn to winter projects.

The more northerly (or southerly) the latitude, the longer the winter is. Here in north west Scotland there’s virtually no practical beekeeping to be done between the start of October and early/mid April i.e. over 6 months of the year.

Some beekeepers fill these empty months by taking a busman’s holiday … disappearing to Chile or New Zealand or somewhere equally warm and pleasant, where they can talk beekeeping – or even do some beekeeping – and, coincidentally {{2}} enjoy some excellent wines.

Others ignore bees and beekeeping for the entire winter and think (and do) something completely different. They build model railways, or practise their ju-jitsu or – if really desperate – catch up on all the household chores that were abandoned during the bee season.

They then start the following season relatively unprepared. Almost certainly, next season will be similar to last season. They’ll make similar mistakes, run out of frames mid-season and lose more swarms than they’d like.

Rinse and repeat.

Alternatively, with a little thought, some reading, a bit of effort and some pleasant afternoons in the shed/garage/lounge, they can both plan for the season ahead and prepare some of the kit that they might need.

As Benjamin Franklin said ”By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.”

Looking back to look forward

I’ve discussed beekeeping records previously (and should probably revisit the topic). My records in the early years were terse, patchy, illegible and of little real use, perhaps other than in the few days that separated colony inspections.

My records now are equally terse, but up-to-date and reasonably informative. I’ve got a numbering system for my colonies and queens that means they can be tracked through the season. The records are dated (rather than ’last Friday’) so I can calculate when important events – like queen emergence or mating – are due.

They’re also legible, which makes a huge difference. I could just about read my old scrawled pencil notes a few days after an inspection, but would have had no chance 5 months later.

By which time I’d have lost the little notebook anyway.

So, at some point over the next few months – sooner rather than later – I’ll look through my records, update the ‘queen pedigree’ table {{3}} and summarise things for the season ahead.

In the spring I’ll update a new sheet of records with a short note on overwintering strength/success and then we’ll be ready to go.

But, in reviewing the records I’ll remind myself about the things I ran out of, the timing of swarm control (when there’s the maximum pressure on available kit) and ideas I might have noted down on how things could have been done better {{4}}.

Reading and listening

The winter is a great time to catch up on a bit of theory. Some beekeepers do exam after exam, pouring over Yates’s Study Notes until they can recite chapters verbatim.

I’ve done enough exams in my lifetime for … a lifetime, and have no intention of doing any more.

However, I’m always happy to do a bit of reading. I’ve currently got The Native Irish Honey Bee and Joe Conti’s The Hopkins Method … (which I’ll return to shortly) by my desk. I’m also partially successfully at keeping up with some of the relevant scientific literature {{5}}.

There are also numerous winter talks available. Some are through local associations, others are available more widely. I ‘virtually’ attended one this evening where there were questions from as far apart as Orkney and Tasmania.

Of particular relevance to Scottish beekeepers, it’s worth noting that our association membership fees are usually significantly less than south of the border (probably because your SBA membership is separate), so you can inexpensively belong to a couple of associations and benefit from their talks programmes and – if you’re lucky – Co-Op purchasing schemes 😉

My attendance at these talks is less good than it should be, largely because I give a lot of talks each winter, but I instead benefit from the Q&A sessions which can be both entertaining and informative.

OK … enough theory

Theory is all well and good, but beekeeping is a practical pastime and just because it’s dark, cold, wet and windy, doesn’t mean there isn’t practical stuff you could be doing.

Competitive beekeepers will use the time to prepare the perfect wax block or bottle of mead for their – local or national – annual honey show.

I’m not competitive, and my wax is pretty shonky but I’ve had fun making (and more fun testing) mead 😉

But there are lots of other things to do …

The known knowns

By reading your comprehensive notes you will know that you ended the season with 5 colonies, that swarming started in mid-May but was over by early July, and that you’ve got one really stellar queen you’d like to raise 2-3 nucs from.

All of which means you are going to need a minimum of 60 new frames next season. These need to be ready before swarming starts.

How did I get to 60?

About a third of brood frames should be rotated out and replaced each season (~20). The nucleus method of swarm control uses the fewest frames, but you’re likely to have to use swarm control for all your colonies (~25). Then there’s a further 15 frames for the 3 additional nucs you want to prepare. Of course, if you’ve got lots of stored drawn comb {{6}} or you use double brood boxes, or Pagden’s artificial swarm method these numbers will be different.

The point is, you will need extra frames next season.

I’m ending this season with about 20 colonies and so expect to need over 200 frames next year, possibly more if queen rearing goes well. Some frames will be recycled foundationless frames but others will contain normal wired foundation.

And what about supers? 2022 was a good year for honey. If you had enough supers and super frames you’ll probably be OK in an average year.

Whether it’s average or not, it’s always easier to build the frames – well-fortified with tea and cake – in the winter, rather than in a rush as you prepare to go to the apiary.

Exactly the same type of arguments apply to any other routine piece of kit – broods, supers, crownboards, roofs, clearers. Buy or assemble and prepare them in the winter.

After Tim Toady try something new

A few weeks ago I introduced the Tim Toady concept. For just about any beekeeping activity, there are numerous ways that it can be completed. There must be dozens of different methods for swarm control or queen rearing, perhaps more.

Of course, however many methods there are, all – at least all the effective ones – are based upon the basic timings of brood development and of the viable fractions of the colony. These things don’t change.

The biology of the honey bee is effectively unvarying.

Queens take 16 days to develop, drones take 32 days (from the egg) to reach sexual maturity. A queen and the flying bees are a viable fraction, as are the nurse bees and young brood etc.

Despite being based around these invariant {{7}} biological facts, not all swarm control or queen rearing methods are equal. Certainly, the end results might be similar, but some methods are easier, use less equipment, need less apiary visits or whatever i.e. some methods probably suit your beekeeping better than others.

My advice about this plethora of different methods to achieve the same ends remains exactly what it was a month ago … learn one method really, really well. Understand it. Become so familiar with it that you don’t need to worry about its success {{8}}.

And then, after a bit of winter theory, plan to try something different.

And the winter is the ideal time to build any new things you might need to try this alternative method next season.

Here are a couple of my past and current winter projects.

Morris boards

Probably 90% of my queens are produced using the Ben Harden approach. It was the method I first learnt, and remains the method I’m most confident with. I’ve found it a reliable small scale method for rearing queens.

But, as they say, ’familiarity breeds attempt’ (at something new) and I’ve always liked the elegance of the Cloake board. This is a split board with an integral queen excluder and a horizontal slide. You place it between the boxes in a strong double-brood colony. By inserting the slide, opening upper front and lower rear entrances and simultaneously closing the front lower hive entrance you render the top box temporarily queenless and enable it to get stuffed with all the returning foragers {{9}}. The queenless upper box is now in an ideal state for starting new queen cells from added grafts.

But most of my west coast bees don’t end up as booming double brooders … the standard Cloake board needs too many bees for my location.

Parallel Cloake boards

Which is where the Morris board comes in. It’s effectively two parallel Cloake boards. Paired with a ‘twinstock-type’ divided upper brood box (or two cedar nuc boxes) it works in the same way as the Cloake board, but only needs sufficient bees to pack a 5-frame nuc so is better suited to my native bees.

You can buy Morris boards … or you can easily build them. This was one of my winter projects in ’20/’21. I’ve used them for the last two years successfully and have been pleased with the results.

I don’t think I understand their use as well as the Ben Harden system … but I will. In particular, I have yet to crack the sequential use of one side, then the other to rear a succession of queens.

Portable queen cell incubator

This was my one big project last winter. Unfortunately, we had a shocker {{10}} of a summer on the west coast and it was rarely used. I did put a few queen cells through it successfully, but queen rearing generally was hit and miss (mainly miss) so it’s yet to prove its full worth.

This is version 2 of the incubator. I’m gradually compiling a list of opponents for version 3 {{11}} that should correct a few things that could be improved – capacity, level of insulation, heat distribution – though the current incarnation is probably more than adequate.

Building – and testing, which actually took a lot more time – the queen cell incubator was a lot of fun. I discovered (and created 🙁 ) a series of problems that needed to be solved and, relatively inexpensively {{12}}, enjoyed sorting them all out. I could work in my warm, well-lit workroom, drink gallons of tea, and dabble with 12V electrickery without endangering my life.

I’ve used it this season powered by a 12V transformer indoors, from an adapter in the car or from a battery with solar backup in the apiary.

However, to use it properly I need to rear more queens … which brings me to …

Queen rearing without grafting

Both the Ben Harden and Cloake/Morris board methods of rearing queens use a suitably-prepared colony in which young larvae are presented. Typically {{13}} these larvae are grafted from a suitable donor colony.

Grafting is perceived by some as a ‘dark art’ – though perhaps not exactly malicious – involving a combination of sorcery, spells, fabulous eyesight and rock-steady hands {{14}}.

It isn’t, but this perception certainly dissuades many from attempting queen rearing.

I find grafting relatively easy and routinely expect 80-90% ‘take’ of the grafted larvae. My sorcery and spells are clearly OK. However, in the future, my eyesight and manual steadiness/dexterity are likely to decline as I get older {{15}}.

I’ve also been reading some papers on how the colony selects larvae to develop into queens. Their strategy isn’t based upon what they can see and pick up with a 000 sable paintbrush … funny that.

I’m therefore going to try one of the graft-free methods of rearing queen cells, and the approach I intend to use is the Hopkins method. Hence the part-read copy of Joe Conti’s book mentioned earlier.

The Hopkins method of queen rearing

This method involves the presentation of a frame of suitably-aged eggs and larvae horizontally over a brood box packed with young bees. Importantly I mentioned both eggs and larvae as, under the ‘emergency response’ colonies preferentially rear new queens from 3 day old eggs.

The resulting queen cells are cut from the frame and used to prime nucs or mini-nucs.

Even with my presbyopia and ’hands like feet’ I should be able to manage that 😉

The intention is to couple the Hopkins method with a 12-frame double-brood queenless nuc box which is subsequently split into several nucs for mating the new queens. And, if that wasn’t enough, I’m hoping I can integrate this with some swarm prevention for the donor colonies … time will tell.

All of that means I need some new kit 🙂

I purchased some Maisie’s poly nuc boxes, floors, feeders and ekes in the summer sales. In the winter I’ll spend some time butchering them with my (t)rusty Dremel ‘multi-tool’ to accommodate the horizontal brood or super frames (and a cell bar with grafts for good measure) before painting them a snazzy British racing green or Oxford blue {{16}}.

More poly hive butchering

I’ve already done a little poly hive butchering this winter.

I’ve got about 20 Everynucs from Thorne’s. These are a thick-walled, well made nuc with a couple of glaring design flaws. However, I’m prepared to overlook these as, a) they’re relatively easy to fix, and b) they cost me a chunk of money and I’m loathe to spend at least the same amount again to replace them.

In addition, bees overwinter fantastically well in them.

I’ve also got a few compatible feeders which are really designed for feeding syrup. You can add fondant, but the bees then need to follow a rather convoluted path to access it.

I decided to modify the feeders to allow both by fitting a syrup-proof dam about half way along the feeder and drilling some 3-4 cm holes through the resulting ‘dry’ side of the feeder {{17}} .

Fondant, ideally in a transparent/translucent plastic food container {{18}} is inverted over the holes and the bees have direct access to it, even in the very coldest weather.

The Ashforth-type syrup feeder still works if needed and I no longer need 8 gallons just to top up each nuc {{19}}. Typically my nucs won’t need feeding in midwinter, but if they do I should be able to position the fondant directly over the cluster allowing them the best chance of reaching it.

Winter weight

This is a practical project carried over from last year. I’m interested in the changing weight of the hive as the colony segues from ‘maintenance’ mode to early season brood rearing. I’ve drawn some cartoon graphs where there’s a clearly visible inflection point, with the hive weight dropping much faster once brood rearing starts.

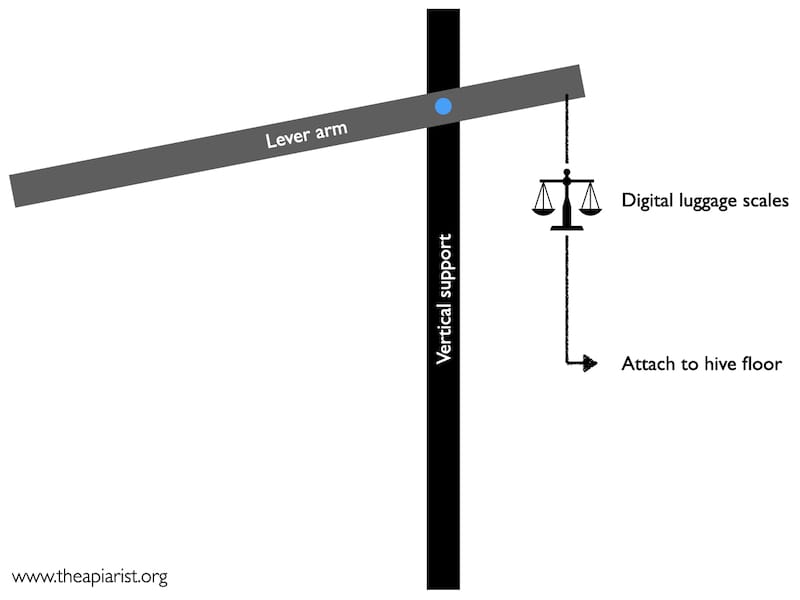

I’m keen to have some real data rather than just my crummy cartoons. I already have the tools for the job, my no expense spared made hive scales. Tests last year showed that these were pretty accurate; I was about 8% shy of the actual weight (which doesn’t matter a jot, it’s the percentage change in weight that’s critical) and, more importantly, produced readings that were reproducible within a percent or two.

However, last year I was thwarted by bad weather, a lack of Gore-tex and an unexpected delay in evolving gills. I’ve now bought a sou’wester and, in the name of science, am preparing to brave the elements every week or so to weigh half a dozen hives.

And in between all that lot I’ll be building frames 🙂 {{20}}

Note

The other winter project already part-completed is moving this site to a new server. Frankly this has been a bit of a palaver, but I think it’s now sorted.

If you had problems connecting over the last few evenings, apologies. If things still seem odd, slow, broken or unresponsive drop me a note in the comments or by email. Of course, if you can’t connect at all you’ll never read this postscript 🙁 .

The changes I’ve made will enable some new things to be incorporated over the next few months, once I’ve got a bit of spare time and have built all of those frames 😉

{{1}}: Unfortunately the only good summer weather we had this year in north west Scotland.

{{2}}: I think not.

{{3}}: A fancy sounding name for a simple list of which queens were used for queen rearing, which were her daughter queens etc., with the intention of maintaining genetic diversity in my stocks.

{{4}}: Or perhaps differently … I won’t know until I try.

{{5}}: And sometimes even contribute to it.

{{6}}: You swot!

{{7}}: And therefore convenient.

{{8}}: With the caveat that as soon as biology is involved stuff goes awry … queens don’t get mated, cows knock the cell raiser over, you break an arm etc.

{{9}}: It’s not quite that simple as you need to juggle some brood frames about, but you get the gist of it.

{{10}}: And not in a good way.

{{11}}: Which may never be built.

{{12}}: It’s about 10% the price of a commercial model.

{{13}}: Though not of necessity.

{{14}}: Though mainly the latter two.

{{15}}: Older, it’s still too soon for old.

{{16}}: Or whatever colour exterior gloss is currently cheapest

{{17}}: Peter Edwards did something similar years ago in a BIBBA newsletter – I make no claims for novelty.

{{18}}: Supermarket mushrooms or chicken typically.

{{19}}: The volume was always a bit excessive.

{{20}}: Or perhaps I’ll go back to Chile where the weather is better, the street art is spectacular and the red wine is fabulous. It’s a long time until Spring and there’s surely enough time to build all those frames as well?

Join the discussion ...